A modest rambler on a winding street in Shoreline might not be the most obvious location for a museum-grade collection of black radical photography. But there it is, on the walls and overflowing into the utility closet: black-and-white prints of Huey Newton, bare-chested and holding a Bob Dylan album; Bobby Seale with fist raised; Alameda State Prison surrounded in solidarity.

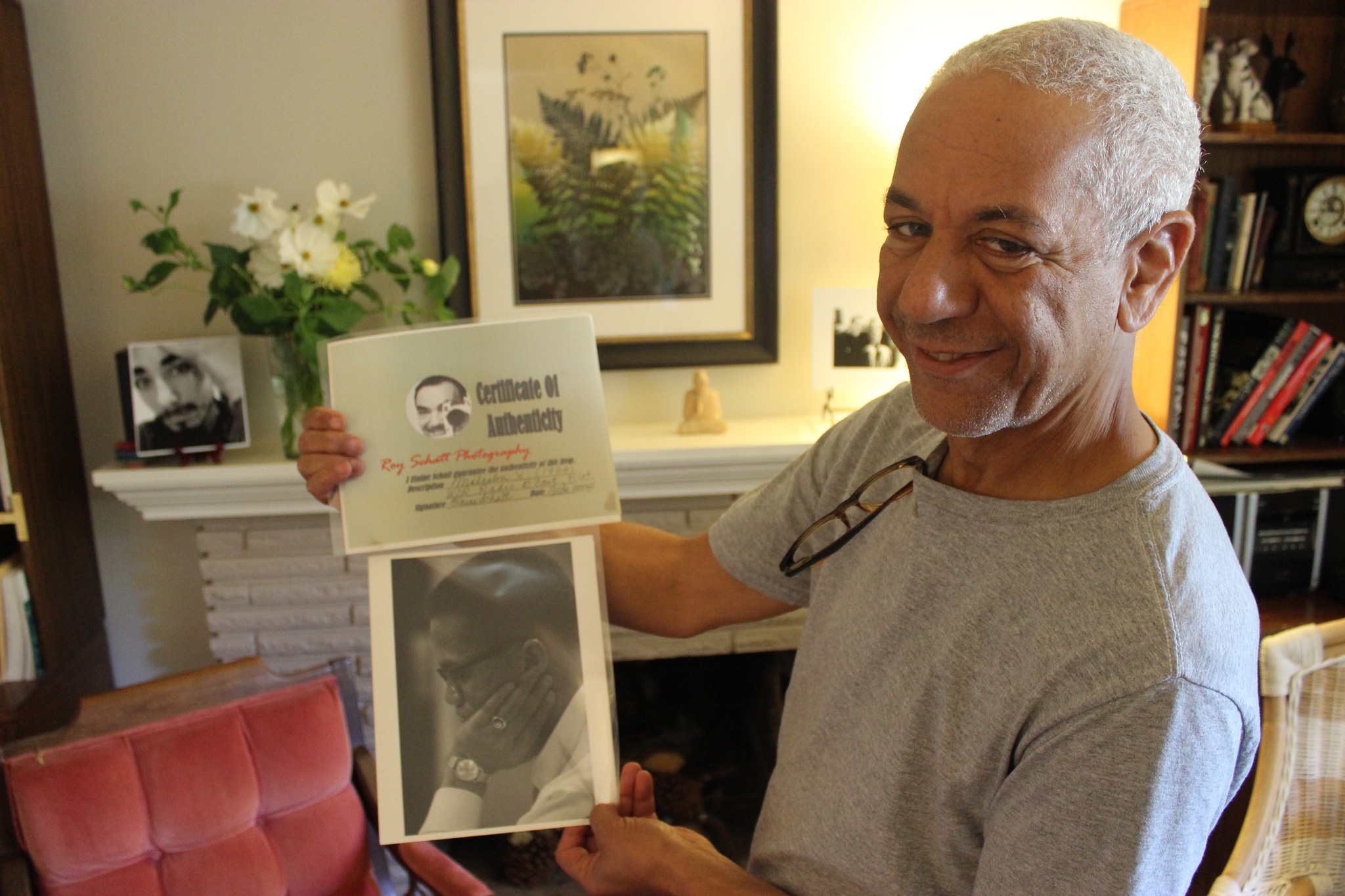

The curator of this unlikely private gallery is Jerry Whiting, a 62-year-old software designer and marijuana entrepreneur who in the early aughts decided to devote a significant portion of his earnings toward buying original photo prints of Black Panthers and other African-American activists from the 1960s and ’70s.

“I didn’t buy a fancy car, I didn’t buy a watch, I don’t keep mistresses. I collect revolutionary black art,” Whiting says over coffee on a recent morning in his home.

Most people visiting his house wouldn’t even recognize the significance of his collection, which generally features vintage prints made directly from photographers’ negatives—the gold standard in fine photography. As such, for years, his growing collection went largely unnoticed outside Black Panther and gallery circles. But that’s beginning to change, slightly, with Whiting’s significant contribution to the Smithsonian Museum of African American History and Culture.

Last month, Whiting traveled to Washington, D.C., to celebrate the grand opening of the museum, to which he donated more than 200 items and sold three dozen more. About 20 of those items are now on display across the museum, which has been lauded as a major milestone in recognizing African American history as an integral part of the American experience.

And despite Whiting’s generosity to the museum, there is still so, so much more. He hauls box after box from his basement, throwing open the tops, not sure of what he will find. “They’re like Christmas decorations!” he says in his booming voice.

Whiting grew up in a prominent black family in Cleveland and describes his mother and father as “Huxtable parents,” referring to The Cosby Show’s depiction of middle-class black American life. While he calls himself a “revolutionary Buddhist” and has long been involved in far-left politics, his interest in the Black Panthers began as an art collector, not a member.

In 1986, Whiting moved to Seattle and later started a tech company, Azalea Software, that specialized in barcode programming. He came into a significant amount of money when Hewlett-Packard began licensing his software in 2002, and soon decided to start collecting art. “It was free fucking money,” he says in his typically salty way. At first he bought photos of flowers, but soon a friend in the art world connected him with Pirkle Jones, a Bay Area photographer who studied under Ansel Adams and was one of the premiere photographers of the Black Panther Party.

Whiting says he was told Jones was close to death, and that when he died his photo collection would go to a museum and no longer be available for purchase. That persuaded Whiting to buy, though Jones did end up living several more years. “Pirkle didn’t fucking die, but it really gave me this gallery of images,” he says.

Whiting had no regrets. He and Jones became friends, and he was hooked on revolutionary photography. He wanted as complete a collection as possible, with a premium placed on those vintage prints. “I’m a collector because I don’t want it, I need it,” he says. “Look, I write barcode software. I’m totally O.C.D.”

Whiting also began to collect Black Panther memorabilia—Party newspapers, correspondence, and the like—and expanded his photography interest to other Black Panther photographers and other significant black figures from the 1960s, including a vintage print of the only photograph taken of Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X together.

He currently has a vintage, original print of Muhammad Ali on consignment at Gibson Gallery in Pioneer Square. “Jerry has selected works for his collection that inspire and provoke thought,” says gallery owner Gail Gibson. “There is a certain acknowledgement of humanity from different eras in the 20th century—and many of these images bring joy, many recount history in the making.”

But it is his Black Panther collection that is truly of the moment. Later this month, the Party celebrates the 50th anniversary of its founding in Oakland. The milestone, along with a resurgence of black activism through the Black Lives Matter movement, has heightened interest in the party, says Aaron Dixon, who helped found the Seattle chapter of the Party in 1968. “Since the police murders have begun to take the headlines, and BLM and Baltimore, many people, particularly the young people, are looking to the Black Panther Party for answers,” he says.

For Dixon, the renewed interest provides Party members a chance to correct some false impressions of the Black Panthers, which he says cropped up in the Reagan years. “In the ’60s and ’70s, the party was looked upon very favorably; the country was much more radical than it is today,” he says. “In the 1980s, the image of the party really went down for a lot of different reasons. The history of the party was suppressed by mainstream media, as well as the education system.”

Photography—as journalism, documentary, and advocacy—played a vital part in the Panthers’ emergence in the 1960s, and it stands poised to play a prominent part in this resurgence as well. To mark the anniversary, photojournalist Bryan Shih has released a new book, co-edited by Yohuru Williams, featuring portraits of Party members, accompanied by interviews and essays with surviving members. Shih says he began taking the portraits five years ago, and hopes that they show another side of the Panthers, beyond images of Huey Newton holding a spear and a shotgun. “That is the image people have of the Black Panthers: a very militant revolutionary force. And that was driven by photography,” Shih says. “When I started taking these pictures, I wanted to show the humans. These portraits really shock a lot of people because you can see so much warmth and dignity and strength. On some people, you see traces of pain.” (At 7 p.m. this Wednesday, Oct. 12, Shih will present the book, The Black Panthers: Portraits From an Unfinished Revolution, at the Northwest African American Museum, 2300 S. Massachusetts St., naamnw.org. Admission is free.)

While his collection is very much in the militant vein, Whiting also felt compelled to donate some of his collection to the new Smithsonian museum to help ensure a positive Panthers story was told. “The Party is not what people think. I dig the hell out of them. When I was told I helped build the [Black Panther] permanent collection at the Smithsonian, I broke into tears.”

dperson@seattleweekly.com