1968 WAS A GREAT YEAR to be young and in love—in my case, with theater. All through the ’60s, new theaters had been springing up in cities all over the country, guerrilla acting bands were taking to the streets, “Broadway” was under assault by the zanies of Off- and Off-off. Even musical comedy, the most popular but also hidebound of forms, was coming back to life: Goodbye, Sound of Music; hello, Hair! And just as the humming, buzzing confusion of it all threatened to overwhelm you, someone came along to make it all make sense.

Hamlet

Mercer Arena runs April 6-19

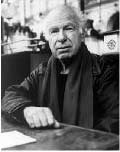

The man who did so was Peter Brook, and more than 30 years after its publication his book-length essay The Empty Space continues to inspire even artists who hadn’t been born when it appeared in 1968. Very few people who write about drama have had anything of permanent value to add to what you find in the ancient Greek Cliffs Notes known as Aristotle’s Poetics. Among those authors, Peter Brook ranks high, maybe highest.

In The Empty Space, Brook explained how shows as radically different as Futz!, Romeo and Juliet, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, and Hello, Dolly! could all successfully hold the stage side by side—why they had to do so if the theater was going to stay alive. For Brook, theater is powerful because it acts out the primal human conflict: our eternal aspiration to the infinite, and our inevitable failure to get any closer than Paducah. He gives theater born of aspirations the honorific “Holy,” and the kind that punctures and deflates them “Rough.” He also shows how both, unless constantly infused with energy from the other, descend into the category of the Deadly, i.e., your typical show at your typical regional theater, something Seattle suffers from no shortage of.

The Empty Space had and has such an impact on youth that it’s a jolt to be reminded that Brook was well over 40 when it was published and that his own roster of accomplishment before its publication was distinctly . . . checkered. His extravagant “theater-of-cruelty” staging for the Royal Shakespeare Company of Peter Weiss’ French Revolution parable Marat/Sade won a Tony when he brought it to Broadway; but he also brought to Broadway such overripe trifles as the gamy French sex farce The Little Hut. His frosty take on Drrenmatt’s sardonic comedy The Visit impressed both Broadway and London; his slovenly staging of the French musical Irma la Douce did not.

IN 1970, WHILE THE THEATER world was still trying to absorb just what Brook meant when he claimed that he could “take any empty space and call it a bare stage,” Brook showed the world what he meant, with a staging of A Midsummer Night’s Dream that stands unchallenged as the most widely admired Shakespearean production in living memory. An “empty space” defined by sheets of dazzling white, actors—also robed in white—nimble as acrobats, tumbling, juggling, swinging from trapezes; evoking as much with their bodies as their tongues the tang and lambency of young Shakespeare’s verse.

That same year, a young UW directing graduate named Burke Walker rented a basement in the Pike Place Market and called it The Empty Space. Over the last quarter century that Empty Space has occupied four successive empty spaces, but you can sense the power of Brook’s notion when you walk into No. 4, in the heart of the free and independent nation of Fremont. This very week, Seattle’s Empty Space welcomes a new leader, Allison Narver: trained at Yale, blooded on Broadway, but willing to confess that her own love of theater was inspired by the Empty Space of 25 years ago. So it goes. Brook’s spirit marches on.

In his own stage work since Dream, Brook’s determination to pare the theater experience back to its unessentials in his stagings has sometimes led to productions that seem not just stripped down but starved. His widely toured Trag餩e de Carmen focused on the drama of Bizet’s great op鲡 comique but lost most of the show’s exuberance in the process. His mounting of Chekhov’s Cherry Orchard—”just a few fine old oriental rugs, scattered here and there, really”—was certainly tasteful, but is exquisite taste in interior decor what Chekhov’s tragicomedy is about?

The Tragedy of Hamlet takes Brook’s process of refinement through compression and omission to new extremes, cutting half a dozen minor characters, several subplots, and nearly half the text to create a six-actor, intermissionless, two-and-a-half-hour distillation of the sprawling original. Even the most abject Parisian worshipers at Brook’s shrine found the production a little dry when it opened at the Bouffes last November. But Seattle’s been reading enviously about touring Brook productions ever since his 10-hour story-theater based on the classical Indian epic poem Mahabharata rumbled its juggernaut way round the world in the 1980s without coming closer than Los Angeles. This is a last chance to see how the 76-year-old Brook’s still-revolutionary ideas play out in practice, and as such it’s an opportunity not to be missed.