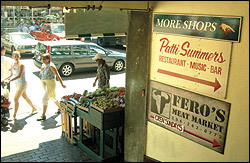

Local jazz icon Patti Summers has been making exploratory efforts to sell her eponymous club, which has occupied an underground pocket of Pike Place Market since 1984. Summers’ tiny lounge—maybe a dozen tables surrounded by Christmas lights, potted trees, blood-red curtains, and a neon pink saxophone—has long served as a springboard for rising jazz musicians. The big-band Jim Knapp Orchestra, for instance, had its first-ever regular gig there on Tuesday nights in the mid-’90s.Knapp says the nightclub is “unique in that it’s run by musicians”—singer Summers and her husband, bassist and saxophonist Gary Steele. While larger clubs like Jazz Alley, Triple Door, and Tula’s book higher-profile acts, Summers frequently hosts open rehearsals, giving her audiences a chance to sample in-progress material before anyone else in town. That brand of informality permeates the place: A given night’s act is listed on a dry-erase board that sits on the sidewalk outside the club. If you order dinner and Summers is the evening’s entertainment, she may inform you from the stage that your meal might take a little while. After all, she can hardly be expected to cook and sing at the same time.

More than two decades after its inception, Summers’ club is still a proving ground for up-and-coming combos. “A lot of times, the young groups who may be college-age or just starting out have been turned down by some of the larger venues in town, [so] they’ll go to Patti Summers and work for the door,” explains Jim Wilke, who produces Jazz Northwest for KPLU. More established acts, like the University of Washington’s experimental jazz band, still perform there, too. “They’re just sick that we’re leaving,” Summers says. “This is like their home. They can come in and play anything they want to play. We’ve never told anybody here how loud to play, what to play, or what not to play. Ever.”

Knapp recalls, “One Tuesday, this guy came in with his entourage, and he seemed to have some means—he was buying drinks for everyone—and he decided he wanted to hear ‘Over the Rainbow.’ Well, we didn’t have an arrangement for it. So he says, ‘I’ll give you $300 if you play it,’ and I counted it off and everyone just made up their parts. And then he did it again, with another $300, and again. . . . He ended up conducting. He was kind of soused by then, and each version got more and more aggressive and bizarre.”

Summers’ club is the kind of place where stories are born, Knapp says. “It’s almost like a movie set. It has a good sound but a terrible piano. And Patti and Gary are both real characters.”

A performer since her teens, the California-born singer ventured up to Seattle in the ’60s to visit her sister, fell in love with Steele, married him in 1969, and played clubs, hotels, and restaurants around the city in the years that followed. Around the early ’80s, according to Summers, “the jobs were kind of drying up,” so she took a risk and opened her own place. “Some of our club-owner friends walked in and said, ‘You guys are never gonna make it six weeks,'” Summers admits. “Of course, they’re all dead now.”

Summers’ importance to the local music scene is hard to sum up, according to longtime Seattle jazz promoter, musician, and writer Norm Bobrow. One thing, he says, is certain: There’s no one quite like her. “She’s a nonpareil as far as [singing] is concerned,” he raves. “There’s no such thing as ‘Who is the best singer?’ but there’s nobody [who] sings better than Patti. I just think she’s marvelous.”