A bad museum experience can be like a death march, trudging for what seems miles among the antiquities at the Met or the Louvre, trying to see the whole collection in a day. And yet a good museum show should involve plenty of walking, too. You feel the difference in your feet—whether they’re tired and you just want to sit in the cafeteria, or you want to keep going, eager to reach the next gallery. You feel the latter, invigorating sensation at glossodelic attractors, if you can get past the show’s title.

About that title: Californian Gary Hill came to Seattle in 1985 to establish the video department at Cornish. By then he’d already been exploring language and phenomenology in his art, filtered through influences including surfing, skateboarding, and LSD. (Born in 1951, he grew up during golden times.) So, psychedelic + glossary = glossodelic. Get it—like a confusion of linguistic terms? And the “attractors” are the things pulling you in, the units of familiar meaning that engage you yet lead you astray, like a rogue wave or some bad acid.

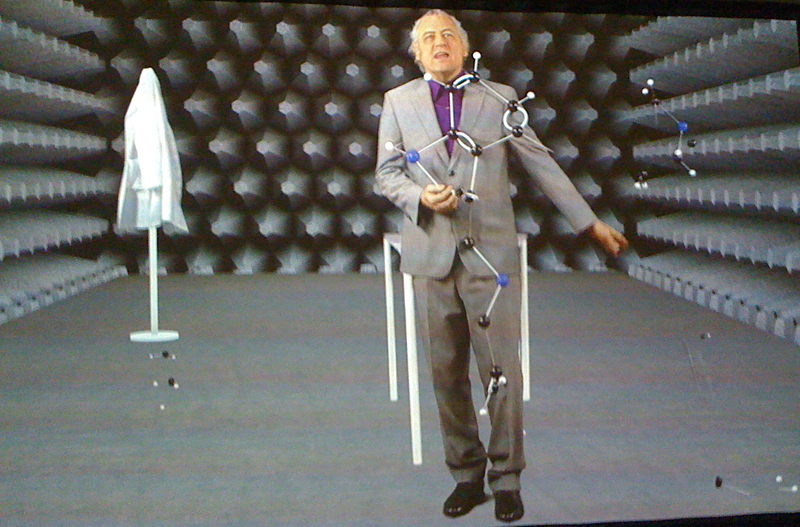

One of the two big works that’ll remain up for the show’s duration, The Psychedelic Gedankenexperiment immediately teases your brain into up/down, left/right confusion. Some kind of nutty professor (actually Hill) is giving a lecture on a pair of video screens, but his words register as gibberish or Esperanto. His movements are herky-jerky and unnatural. It’s like a nightmare flashback to freshman-year Physics 101—and you don’t understand a word he’s saying! But wait, maybe you’re not dreaming. Maybe you’re not high. Sit on the weird foam stools, put on the 3-D glasses, and you may recall the backward-talking dwarf dream in Twin Peaks. The phonetic companion text on the wall (LSD is “the most powerful and in time the most influential work of art throughout all of history”) helps translate the 22-minute videos—only one, actually, synchronized on the two screens.

Reality is in there someplace, but it’s been refracted, its meaning redirected; and Hill similarly splits our perceptions with stereo viewers, prisms, and curved projection screens in the smaller pieces that will rotate during the summer. (Thirteen works are currently on view.) Hill’s 1987 DIG—originally commissioned by the Henry—will return in August and run into January. It’s a two-story installation that he’s described as the “electromechanical/ alchemical mining of a wheel and its concomitant metaphor.” So get ready for that.

One of Hill’s earlier interactive works is Mesh (1978), in which floor sensors trigger crude, pixelated filming of the visitor walking through the gallery. Ephemeral little mini-portraits result on four video screens of varying resolution, but the image capture is deliberately imperfect. One screen might get the color right, another the facial profile, but you can never integrate the four aspects as you crisscross the room. There are four strands of meaning—something like the blind men and the elephant. As with The Psychedelic Gedankenexperiment, our subjective perceptions—that’s the phenomenology of it—are being faceted and separately channeled. Staring through the stereoscopic viewer in Beauty Is in the Eye at two evil clowns (again, only one evil clown) achieves the same effect.

Hill’s biggest piece further separates the eye and I. The maze component of his 1995 Withershins covers most of the floor of a large gallery, but it wouldn’t obstruct a mouse. The grid is maybe three inches tall, so you can step over it or enter at any point. But if you obey the audio cues triggered by the sensors beneath your feet, a pattern or path emerges. Stimulus yields instructions; there’s feedback underfoot. And a wall display of Post-It Notes serves as a record of obedience or intentions. “The left hand spoke,” reads one note. “Hand apprehends hand,” says another. Video screens present silent instructions in sign language; these two guides, male and female, are assigned to the two entrance points. Hill is again dissociating your perceptions and sense of individual agency (the I in I am going to do this), like the funhouse mirrors at the old penny arcade.

It’s all very disorienting, enjoyably and intentionally so. My favorite video here is a slow, meditative helicopter shot of a surfboard bobbing in the sea near Hawaii (Isolation Tank), a three-minute take running in continuous loop. Says Hill of the gradual zoom-in image, “There’s a confusion that takes place between point-of-view and where you are”—and who you are, he might well have added.