A “swarm” is a migrating colony of bees—and an apt metaphor for the language of Jorie Graham. In her poetry, the words stream across the page, seething and shimmering, flocking and scattering, always rushing onward—sometimes straight at the reader, as if Graham wanted to colonize us, to make hives within us for her poems.

SWARM poems by Jorie Graham (Ecco Press, $23)

Of course, the queen leads the charge. Graham is a reigning poet of her generation; she has won numerous honors, a Pulitzer and a MacArthur “genius” grant among them, and currently she holds professorships at Harvard and the prestigious Iowa Writers’ Workshop. She is paid this kind of homage because she has devoted her career to a poetic task of considerable philosophical grandeur and difficulty.

Graham seeks to capture reality through description, despite her full awareness that words conceal and distort more than they reveal—that language is a veil and a mirror as well as an eye. Accurate, unmediated experiences of the concrete world are impossible to achieve or transcribe, but the ceaseless labor of Graham’s poetry is to know and embody that pure experience. So although the settings of the poems are usually unremarkable and the actions are primarily quiet observation, each poem is tensely dramatic—a sensuous, electric, weighty yet astonishingly athletic, exhausting, and ultimately futile attempt to converse directly with the world.

In Swarm, Graham’s struggle with her surroundings all but threatens to annihilate them. Her willingness to hazard new and risky poetic regions and forms here is to her credit; but the shorter lines and airier spacing tend to frame her customary remarks to herself in isolation, and the effect is that a poetic Personality, instead of a perceiving intelligence, stands at center stage. “I am not lying. There is no lying in me,” she avows in the opening poem, later murmuring to herself, “Grieve. Have/hope./*/Have sights truth in them?” Such sentiments multiply, swelling Graham’s customary quarter notes of anguish into a self-pitying symphony. Poems like “Eve” and “Swarm” contain the old, sterner magic; others in the book might have more of it if the poet weren’t seeming to parade her burden of responsibility.

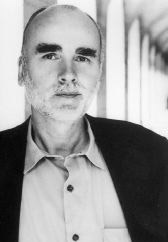

Graham’s work is philosophically significant, but that doesn’t always make it interesting as poetry. Critics have remarked that although her language often dazzles with its passion, insight, and originality, few of her lines are memorable. But like the crowd of people in the Giotto fresco adorning this lovely book jacket—all of them swarming, wide-eyed and eager, for a glimpse of the wonder located just beyond the frame—we flock to read her work. If Giotto’s worshipers could turn the corner at the edge of the volume, they’d find on the back the queen herself in full-page regalia: her signature black velvet and chunky jewelry, her famous hair, her beautiful brow tragically furrowed with the knowledge that we cannot truly know. Even with her help.