One autumn day in 1963, the mother of a yet-to-be best-selling author was invited down to her basement by an as-yet-to-be-convicted rapist-murderer. Something was wrong with the washing machine, he claimed, with a look she would later say was “indescribable”—in a bad way. Her instinct was that if she’d gone down the stairs, she’d never have made it back. However, she opted not to report the incident, since nothing technically happened.

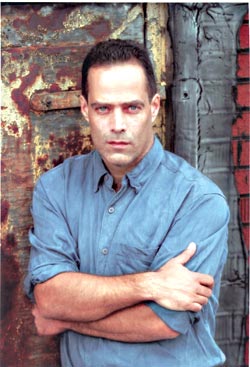

That man was the Boston Strangler. Albert DeSalvo was then part of a small construction crew working on the house of the parents of Sebastian Junger, still in diapers and three decades away from writing A Perfect Storm. What a coincidence! Not a bad book idea either, right?

And it gets even more lurid. The next day, neighbor Bessie Goldberg was raped and murdered only a few blocks from the Junger’s home. The killing had all the signatures of a series of crimes that had been plaguing Boston for the last two years, and yet DeSalvo was never linked to it. Instead, the man charged and convicted was a petty criminal and alcoholic named Roy Smith, the last person inside the Goldberg’s home. He’d been dispatched by an employment agency to do some cleaning work. An African American in a city so racially polarized, his very presence on the streets of Belmont inspired a phone call to the police. Smith was subsequently sentenced to life for murder (but not rape). He died soon after his pardon in 1976. Meanwhile, DeSalvo’s sensational confessions weren’t always supported by the evidence; convicted for other slayings, he was killed in prison in 1973, but never mentioned the Goldberg murder.

OK, by now you’re probably thinking, like me: Wow, this is going to be a great true-crime account, in the tradition of In Cold Blood. Unlike Capote, however, Junger wasn’t there—not for the crime, trial, or aftermath, which is Belmont‘s great shortcoming. In Junger’s comprehensive exhumation of the Boston Strangler case, he explores many possibilities about the Goldberg murder, and while the book’s starting point is his personal connection, this element is never overplayed. Belmont covers a lot of ground, from the pathology of serial killers to race relations in northern cities of the early ’60s to the Mississippi of Smith’s youth. It’s also very much about an imperfect justice system. While at times the book feels thin and occasionally delves into melodrama, there’s seldom a dull paragraph.

Goldberg’s family has criticized Junger for factual inaccuracies and accused him of trying to exonerate Smith and indict DeSalvo, which Junger has denied. Reading Belmont, it seems clear that Junger believes, with a lot less than absolute conviction, that DeSalvo likely was the killer. In this way, the book is at odds with itself: The author posits a fascinating story with more than a few speculative scenarios, but the reporter can’t back it up.