WHEN GRACE COMES IN

Seattle Center, Seattle Repertory Theatre, 206-443-2222, $10-$46 7:30 p.m. Tues.-Sun.; 2 p.m. Sat.-Sun. ends Sat., Nov. 10

AFTER A WHIMSICALLY mysterious Polish doctor runs a test on her, the nervous Margaret Grace Braxton is told that she should be concerned about her heart. “They’ve already ruled that out,” she protests, citing other doctors. Ah, yes, the man twinkles sagely back at her, but “you can never rule out the heart.” Welcome to Oprah’s Play Club.

It’s times like this when I worry about Seattle Repertory Theatre. Here’s a moneyed, Tony-winning company with the means to try anything new, but it goes running after the recycled. Last spring, it spent its resources on Robert William Sherwood’s dead-on-arrival “new” play The Last True Believer, a hokey, ’50s-style drawing-room thriller tarted up with musings about the effects of the Cold War on the international psyche—Dial ‘C’ for Communist, basically. Now the theater has dipped into its wallet to bankroll When Grace Comes In, the latest work from Heather McDonald (Dream of a Common Language) that reads exactly like some didactic ’70s women’s consciousness-raiser —without the swift, invigorating kick of righteous anger that a lot of those plays had. Think I’m Getting My Act Together and Boring You at the Rep.

McDonald’s piece has present-day Grace (Jane Beard) realizing midlife that maybe giving up her cherished art career to bear three children by Sen. Bill Braxton (Mark Chamberlin) wasn’t such a good idea after all. Her mother (Anne Gee Byrd) is dying after a lifetime of regrets, and Grace, too, feels her personal identity and even her memory slipping away (“I want to remember what I want to remember about myself,” she says, frustrated). When that fanciful doctor (Kevin C. Loomis) tells her she needs to “move” and “breathe,” well, she knows it’s time to put on some Helen Reddy and get the hell out of Dodge.

At times, it seems McDonald would have liked to shape something resembling Margaret Edson’s Pulitzer-winning Wit, and grant us an evening with a puzzled, educated woman forced to re-evaluate her life choices. But the playwright just doesn’t have anything deep or original for Grace to share with us, which is particularly irritating because the show has been written and staged as though it were startlingly fresh. Sen. Bill actually says “Home is where your heart is” at one point, and we’re supposed to “hmmm!” and nod our heads. And director Sharon Ott’s enviable gift for pretty physical staging is as emotionally hollow as ever; you could stop the production at any moment and take a perfect publicity photo, but you don’t believe a single relationship onstage. (McDonald’s attempts at surrealism—the eccentric doctor, an encounter with Grace’s dead parents in ball costumes, et al.—come off both in word and deed like spirited children’s theater).

Not that McDonald doesn’t have her moments: There’s a winning observation from Grace’s late-night DJ spiritual guide (Stephanie Berry, smoothly funny in a dumb role) about installing Hank William’s mournful “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry” as America’s new national anthem. In another clever bit, a sentimental wedding memory is depicted twice—once in the bloom of love, then again with the jaded regret that reflection has granted it. (Just to make sure we get it, of course, an empty wedding dress looms menacingly in the background).

Here’s something else, though: Grace may turn the most bleeding-heart liberal into a carping chauvinist pig. Our heroine’s need for liberation seems to stem not so much from that timeless sensation of being trapped by stifling societal roles, but rather from a very questionable decision to simply change her mind. No need to worry about your kids’ emotional scarring when you can flee to Venice, wear paisley pants, and restore Tintoretto works with your sympathetic, lonesome, and queeny new gay friend (yep).

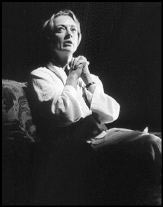

The performers are fine— Loomis, in a number of roles (including the gay Fabrizio), and Chamberlin as the senator are doing all they can—with the excruciating exception of the lead. Beard’s delivery places greater import on how singularly something can be phrased rather than what it actually means. She spends the . . . entire play . . . speaking . . . with a halting . . . artificiality . . . and . . . placing . . . odd emphasis on . . . randomly selected . . . words. (It’s never a good sign when your date claws her fingernails into your forearm 15 minutes into the thing and murmurs “William Shatner.”) Imagine two and a half hours of this and try to calculate how far up the wall you’ll be.

McDonald may want to rescue the world from self-imposed imprisonment, but there’s no saving Grace.