Persistence of Vision

Runs Fri., Aug. 16–Thurs., Aug. 22 at Grand Illusion. Not rated. 83 minutes.

Don’t make a masterpiece. Or at least don’t set out to make a masterpiece. That’s one of the lessons of this compulsively watchable documentary about celebrated animator Richard Williams and how he never finished his designated magnum opus.

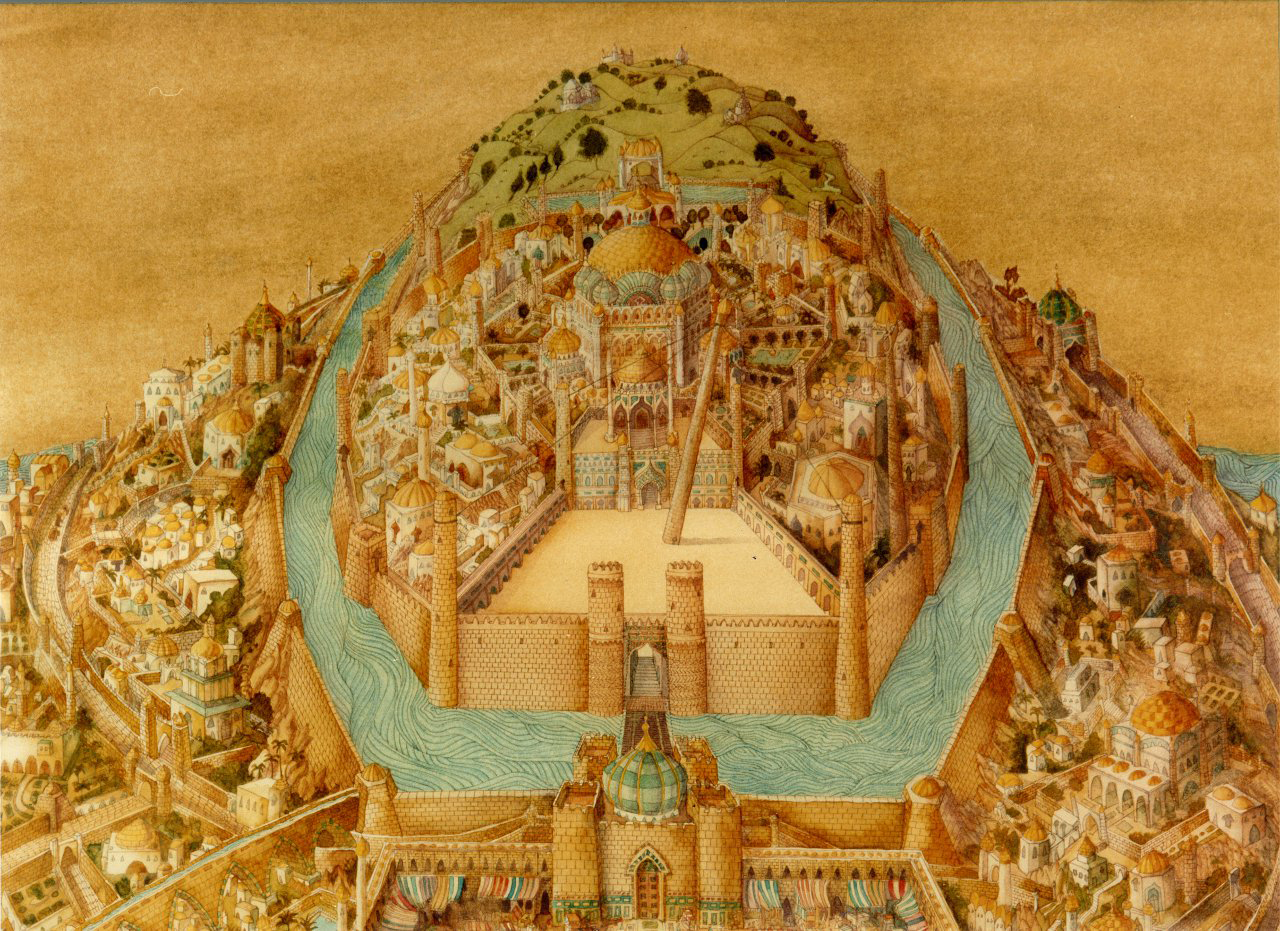

Williams is a Canadian, now 80, who ran a profitable animation studio in London for decades. Expert at turning out brilliant short films and TV commercials, Williams began on his real work—the labor of love that all the other stuff was paying for—in the early ’60s. His original concept for the feature involved tales of the folkloric Middle Eastern character Nasrudin; and although the concept veered away from that character, the colorful Arabian Nights theme persisted throughout the decades. Yes, decades: The project lost backers, missed deadlines, underwent rewrites, and outlived some of its original animators. Williams dawdled so long that he was forced to endure the success of Disney’s 1992 Aladdin, which bore a suspicious resemblance to his own work-in-progress. At one point in the process, Williams won two Oscars for his boundary-pushing work on Who Framed Roger Rabbit and snagged big-studio backing for his masterpiece, now titled The Thief and the Cobbler. And this is where it becomes clear that money wasn’t the main issue with completing the picture—Williams was.

Persistence director Kevin Schreck assembles a big group of Williams’ former employees to weigh in on the heartbreaking arc of this project. He does not, however, have Williams himself—the animator refuses to discuss The Thief and the Cobbler these days—but we hear a lot from Williams anyway, thanks to sizable clips of him talking about the film in various phases of its development. He isn’t shy about the word “masterpiece,” nor about wondering what Rembrandt would do in his position. Williams emerges as a recognizable cracked-genius stereotype: exacting in his methods, specific in his vision, and rough on subordinates who don’t see working 80 hours a week as normal. The completed segments of his dream film show astonishing, hallucinatory images, but his associates acknowledge that Williams never really had the overall storyline plotted out, even after he’d spent millions of dollars on it.

Stories about doomed crusades have a built-in appeal, especially when there’s a grand, visionary angle. Persistence of Vision has all that, and even if you know how the train wreck is going to end, the spectacle is hard to resist.

film@seattleweekly.com