“Maybe we can’t move beyond capitalism by next week, but we can sure as hell take a vacation from it,” beckons Red May on its website. Set to conclude this weekend, Red May is a festival comprising talks, film screenings, and public demonstrations on leftist thought, like communism and democratic socialism. Its schedule is robust and heady, filling nearly every single day this month with gatherings on universal basic income, alternate economies, and automation. Glancing at it feels like registering for college classes, which can be fun or traumatic, depending on who you are.

What makes the festival unique among political conferences is its expansive scope and decentralization. On the whole, the events are casual, taking place at bars and small galleries, likely with bottles of wine and Styrofoam cups. And unlike college, most events are free. Red May’s approachability may be because its organizers aren’t politicos, but artists and curators, such as Philip Wohlstetter of Invisible Seattle, Hami Bahadori of This Might Not Work, and Justen Waterhouse of Institute for New Connotative Action (INCA). (I should mention that I moderated a Red May panel called “Luxury for All.”) Two talks were by writers who had published books about art: Jasper Bernes, who spoke at INCA, and Jaleh Mansoor, at Glassbox Gallery. In case you missed it, here are my notes:

The Work of Art in the Age of Deindustrialization by Jasper Bernes

As a poet and art critic, Bernes is interested in the ways that artistic and poetic experimentation have mimicked patterns of the workforce and vice versa. One example he gives is Silicon Valley’s incorporation of the environmental and social principles of “hippie modernism” in Haight-Ashbury (ground zero of 1967’s infamous Summer of Love). The countercultural ideas of communes and “returning to the land” seeped into the computing sector, perhaps most emblematically in Stewart Brand’s Whole Earth ’Lectronic Link, one of the first online communities. The WELL and Whole Earth Catalog’s networks were profound, influencing technologists such as Alan Kay, inventor of the MacBook.

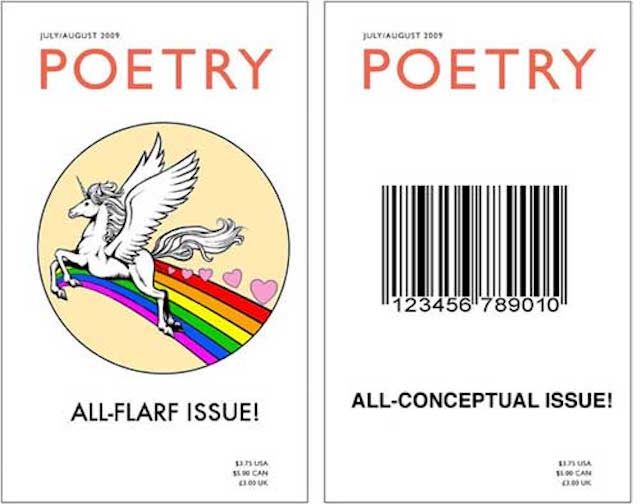

Bernes seems more interested in specific cases than in drawing larger implications from these instances. He also mentions Hannah Weiner’s code poems, in which she used the maritime code for signaling between ships in poems that Coast Guard members then performed at Central Park. Another example is Flarf, a poetry movement in the 2000s written through collaborations on e-mail listservs, which, according to Bernes, “foregrounds the conditions of contemporary office work in the age of social media.”

“Flarf and Conceptual Writing in Poetry Magazine” by Kenneth Goldsmith. From the July/August 2009 Issue of Poetry Magazine.

Marshall Plan Modernism by Jaleh Mansoor

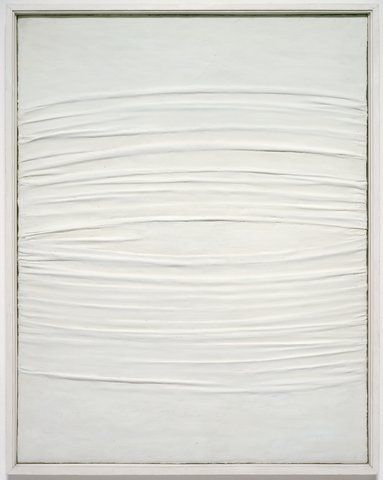

A professor at the University of British Columbia, Mansoor argues against the widespread idea that “expressive painterly gestures were quickly absorbed by official culture,” specifically that the work of artists such as Lucio Fontana, Alberto Burri, and Piero Manzoni was comparable to American abstract art. She states that in Italy after WWII, Italian painters were searching for gestures “that could adequately express the incipient war between labor and capital” resulting from The Italian Miracle (a period of economic boom that critics have characterized as a period of greed and cultural stagnation). That search for expression led to the procedural violence present in Fontana’s slit canvasses and Burri’s burnt plastics—antagonisms toward American art of the period as well as rejections of the nationalistic legacy of Italian futurism.

In studying this particular moment, Mansoor asks, “What ways did those artists transcend the critique of labor?” and “What is the kind of class consciousness that may or may not be in the work?” Manzoni’s mechanical tracing of lines on rolls of paper, for instance, can be argued to evoke the increasingly automated labor of postwar industrialism.

Piero Manzoni. Achrome (circa 1958). Walker Art Center.

A General Note About Red May and the Public-Forum Problem

When Mansoor’s talk ended, an audience member made the last point: “I’m hearing a lot of multisyllabic words,” addressing the evening’s thick academic-speak. “What you’re talking about is the stolen means of production, which is about hip-hop. You can look to hip-hop if you’re looking for a global revolutionary movement. And I got there without talking about M-C-M.” (The M-C-M cycle is Marx’s description of the process of economic exchanges: Money-Commodities-Money.)

Reliance on academic language wasn’t unique to Mansoor’s talk, but characteristic of the handful of Red May events I attended. This comment unlocked my unease around the festival, which was related to my observation that although the schedule did include a diversity of speakers, audiences often were not.

Let’s think about who willingly attends public forums about critical theory and politics. Here’s what you can predict: Most of them likely digest the world with academic language. There will likely be a white man who will interject every time he has a question or point, structuring the entire conversation around his understanding. If you’re a person of color, there will likely occur a point when you either press your pen firmly to your notebook in silent aggravation, or speak up about race and be that Spokesperson of Color. Against these gambles, it’s hard to choose the public forum over, say, reading by yourself. This is unfortunate, because who is impacted by capitalism more gravely than people of color, the poor, immigrants, and other marginalized communities?

Red May should occur every year. It has felt fruitful and rare to gather with strangers and friends to talk about alternatives to capitalism. Judging by the steady attendance, it seems that the city agrees. Yet if the dynamic doesn’t change, I fear that it all amounts to an empty pastime, a valorization of thought with the same people who can pontificate all day. A point of reflection for the organizers: Does Red May merely want to create space for existing in-groups, or does it want to welcome a diversity of people curious about these ideas? If the latter, it will involve heavier moderation, cutting off the white guy who has yet another off-topic anecdote, creating horizontal exchanges of ideas aside from lectures, and offering learning opportunities aside from theory. Viable alternatives to capitalism must involve shifting the dynamics of who feels comfortable to speak and what type of knowledge is prioritized.

There’s about a week left of promising Red May events. I hope that its curators, and anyone else who wishes to organize public spaces of learning, will consider who is showing up and who is coming back.

Red May, Various locations, redmayseattle.org. Free. All ages. Ends Sun., May 28.

visualarts@seattleweekly.com