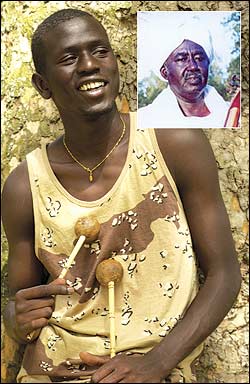

Like most big countries, the Republic of the Sudan is a mess. Deforestation, famine, perpetual drought, and countless other major-league problems have only complicated the devastation wrought by a civil war (north and south, religious and ideological differences—sound familiar?) that has ravaged the nation for the better part of its 49 years. After several years as a child soldier in the rebel army, rapper Emmanuel Jal‘s life took a massive turn for the better after a British aid worker smuggled him into Kenya. But the Nairobi-based activist MC, now 25, hasn’t turned his back on home. After scoring a No. 1 hit in his adopted country with “Gua” (“Peace”), he was invited to perform at the momentous treaty signing by Sudanese Vice President Ali Osman Taha and rebel leader John Garang (since assassinated) earlier this year.

But well before the uneasy truce went into effect or he macked at Live 8, Jal and veteran northern Sudanese bandleader, singer, composer, and oud player Abdel Gadir Salim made an unprecedented gesture—teaming up to record Ceasefire, which World Music Network releases on Sept. 26. On the album, consummate crooner Salim gives Jal the lion’s share of mike time. On opener “Aiwa,” Jal’s limpid butterscotch tenor flows like a cross between 50 Cent and a brook. While occasional forays into English—as when he gently proclaims “It’s not like a mystery/ If you got love/You got the victory”— provide welcome signposts for those of us not fluent in southern Sudanese dialects, it’s the rapper’s command of his native tongue that provides much of the song’s momentum, along with Salim and his seven-piece band’s precise, measured funk.

Life-and-death issues aside, what’s most interesting about the album is the extent to which both the turbaned Salim and crew-cut Jal, whose accoutrements lean toward Western street fashion, find common ground in the music of the African diaspora and its outward echoes. Salim regularly coaxes jazz and R&B figures out of his oud, sometimes forcing Arabic into dancehall like a ship into a bottle when he sings. But apart from Clintonesque (George, thank you) chartbuster “Gua,” the album’s patron saints are Bob Marley and Fela Kuti. Like Jal’s choruses (complete with female backing vocalists), the solos of Salim saxophonist Hamid Osman Abdalla bear the unmistakable influence of the Kuti line. Fortunately, Osman plays more like Fela’s son, Femi.

From the watery funk guitar that rides Moises Santana’s opener “Alegria,” the diasporic tributaries that nourish The Rough Guide to the Music of Brazil: Rio de Janeiro (World Music Network) are more diverse still. Granted, the South American giant’s biggest metropolis—birthplace of samba, bossa nova, and tropicalia—ranks among the world’s most fecund sources of original Afro-European currents. But productivity hasn’t stopped the city from importing every flavor it can get its ears around. Nei Lopes’ galloping “Samba de Elegua” gets much of its color from frantic salsa horns; Fernanda Porto’s subtly steamy “So Tinha De Ser Com Voce” rides an understated U.K. garage beat; on “Tem Espaco Na Van,” Ed Motta provides a compelling simulacrum of Tavares circa 1980, complete with boingy synth interlude. But it’s the compilation’s 100 percent homegrown tracks—particularly Quinta’s Veloso-esque “Construcao” and Paulo Bellinati & Monica Salmaso’s spare, acoustic “Canto de Ossanha”—that might well move any sensible soul to consider moving south.

Caetano Veloso’s “You Don’t Know Me” opens Edwin Houghton and Jamal Ali‘s globalist mix CD, 48 Hours in Transit, due on the newly minted Subscript imprint soon. A raison d’être more removed from Ceasefire‘s is hard to imagine; the disc exists largely to help hawk Brooklyn-based parent company Triple 5 Soul’s wearable wares.

Still, Houghton and Ali’s mix contents are far from apolitical. In their youth, Veloso and Tropicalia-movement partner Gilberto Gil—now Brazilian minister of culture—enjoyed their share of serious run-ins with the generals who ran their country at the time, much as the military calls the shots in Sudan now. Fela Kuti’s lifelong battle with Nigeria’s military dictatorship is the stuff of legend. While the cariocas skew sunny—Gil with the lilting “Domingo No Parque”—Fela’s revolutionary ardor shines through even on the battalion of horns and tightrope guitar of his instrumental, “Water No Bring Enemy,” which also pops up.

But all politics and no play would probably make for a damn dry amalgamation, especially over the course of 48 Hours in Transit‘s 30 tracks. Houghton and Ali offer a thoroughly panoramic tour of the African diaspora and its affinities—not unlike DJ /rupture’s sets, minus the overlays—hitting Angelique Kidjo, Lata Mangeshkar, A.R. Anand, Cesaria Evora, Hugh Masekela, Elephant Man, Beenie Man, and a score of others in the mix’s pancontinental peregrinations. There’s clearly no place for nationalism in Houghton and Ali’s agenda, but the duo’s finest groove-mining moment arrives with a track from a country bigger and messier than even Sudan or Brazil: the U.S.A. On Yam Who’s transcendent “Spiritual” remix of Raphael Saadiq’s “Skyy (Can You Feel Me),” soaring synth strings and samba bass help make the lover’s anthem more post-soul than neo; Saadiq’s impossibly close duet with Rosie Kaye renders such silly distinctions irrelevant—for the moment, at least. What was it that Jal said about love again?