Since the mid-’80s, Divine Styler’s been on a wild ride that epitomizes, perhaps more than the experiences of any artist, rap’s trials during those tumultuous years. His path has taken him from: 1) eager MC trying to get put on; to 2) rapper with a crew; to 3) criminal; to 4) cautionary tale; to 5) religious convert; to 6) missing in action; to 7) underground icon and nostalgic fetish item. All the while, thanks to his mind-bending delivery and thick religiosity, he’s managed to never truly be in fashion, but like the hungriest rappers, has persevered with a little help from his friends.

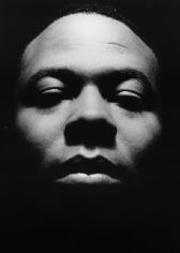

Divine Styler

Wordpower 2: Directrix (Mo’Wax/ Beggars Banquet)

Born and raised in Brooklyn, Divine found himself falling in with, of all people, Ice-T and his Rhyme Syndicate. Easily the most lyrically and spiritually advanced of the crew, he soon outgrew it (though not before spending a stint behind bars for gun charges unrelated to his rap life). His two albums, both long, long, long out of print, were critically acclaimed if commercially underwhelming. Word Power (Epic, 1989), his debut, is undeniably funky, very much a product of the post-Bomb Squad aggro approach to positivity. Hell, Divine even flipped the same scratchy squeal House of Pain used on “Jump Around” on his black-and-proud screed “Ain’t Sayin Nothin.”

His follow-up, Spiral Walls Containing Autumns of Light (Giant, 1992), was something altogether different. By the time of his second album, Divine was eminently less concerned with conventional hip-hop excellence than with the expansion of his own mind, and he made Spiral Walls a bizarre testament to the powers of religion over tracks that mixed Hendrix-esque guitars with atmospheric dub. Rumor has it that Divine was completely clean—of drugs and crime—when he made Spiral Walls, but his verse is so dense, his music so obscure, that it’s almost impossible to imagine anyone sober making it.

So what becomes of an artist so ahead of his time he’s never in fashion? Only recently has the underground begun to catch up to Divine’s wordplay. A couple of years ago, an intrepid Canadian hip-hop journalist named Fritz the Cat launched a ‘zine titled In Search of Divine Styler. Few appreciated the homage, but it eventually did find its way to the man himself, who slowly began to reemerge from radio silence. Last year saw him release his first album in almost a decade, Wordpower 2: Directrix, independently (on DTX). Cognoscenti twittered excitedly and cool-hunters began scavenging—most notably the folks at UK hipster label Mo’Wax, who reissued it early this year. Then, in a bizarre twist, US imprint Beggars Banquet chose to (re)issue it here in the States. Got that? Good.

Now go get it. Wordpower2 finds a middle ground between Divine’s first two records, returning to a semiconventional flow structure (and losing the singing) while creating music that sounds as if it’s been geysered up from the magma layer. And there is the message; religion is spread through this album like butter on pancakes. The two-minute opening Arabic incantation is a position statement: For Divine, spirituality and music are woven together inextricably. However, unlike most Christian hip-hop (the only non-Islamic religious group that has a scene of substance), Divine understands that music is just as important as words, often more so.

But naturally, Divine does preach, and it’s his ideological integrity that carries this album. “We need to reconstruct the black race,” he warns on “Triple Irons.” On “The Grand Design,” he maps out Allah’s master plan in alarming detail, proudly proclaiming, “While some chose to dwell, I chose to tell/While some chose the L, I chose to exhale.” But it’s on the rumbling “Make It Plain” where his message is clearest: “The struggle and strife black life demand that/they understand we in an economic dope fiend/We just flip to hustle legit and spend clean/Enterprise the game cause we original man/stole from the motherland.”

“This is the ill black calculus,” he asserts on “Before Mecca,” but thanks to his spiritual devotion, there’s really no arrogance to his boasts. Instead, what’s there is a silent, steady confidence, a refreshing contrast to the insecure boasting of his hip-hop brethren. Being such a marginal figure for such a long time has its advantages; when there’s no pressure to perform, it’s easy to evolve naturally within your art. Like the heatprint image on the album’s cover, Divine’s words are somewhat obscure, but also like the album cover, his true wisdom shows through with bright, squint-inducing waves.