To get to the Bumblebee Boxing Club inside the Union Gospel Mission near the corner of Martin Luther King Way and South Othello Street, you must navigate a vast parking lot that adjoins the saddest Safeway in Seattle and borders dilapidated churches with hand-lettered signs, like the ISRAELITE CHURCH OF GOD IN CHRIST WITH THE NIGHT PRAYER AND BIBLE BAND, and businesses such as Dy Vang’s TV/VCR Repair Shop and the Sunlite Hair and Nail Salon.

Derelicts wander across the Safeway lot. One, clad in filthy sweats and high-top tennis shoes, moans and lashes out at imaginary demons, while another grubs inside a dumpster for rotting fruit.

Seattle is in the midst of a nearly unbearable heat wave. Seattle Patrol Officer Sam DiTusa, age 51, sits baking in his own car on his own time, surveying the passing human carnage. Sweat leaks down his bull neck. He shoots me a distracted grin, rolling his eyes. After 12 years working undercover on the vice squad, he’s seen this all before. His fists, roughly the size of large pork roasts, idly twist the steering wheel, the tattoos of his children’s names riding the flex of biceps like illustrated surfboards on a following sea.

DiTusa needs a favor: a temporary place to live and maybe a job for Dashon Johnson, one of his up-and-coming fighters, who’s relocating from Escondido, California.

“We’re a little early,” says DiTusa. “Bee will be here. You could set a watch.”

Not long thereafter a short, buff, energetic black man opens the door of a vintage Cadillac Eldorado. There is a slight wobble in his step. He wears a black shirt with a screaming yellow slogan: “KEEP YOUR HANDS UP AND YOUR STINGER SHARP!”

Could it be Bumblebee? “Well, yes, sir, that’s me, aka ‘Willi with an I not a E’ Briscoeray. Bumblebee works well enough,” he replies. “You come to a place most every day for 20 years, word’s liable to get around.”

On cue, a dozen kids come running, seemingly from nowhere—one with bandages that need wrapping, three small black girls bouncing up and down as if on pogo sticks, and a shy Native American boy with downcast eyes who hangs back, rubbing his hands over the hood of Bumblebee’s car.

The 70-year-old Bumblebee was once one of the top amateur flyweights in the United States, training under the legendary Eddie Futch in south-central L.A. back in the ’60s. Bumblebee and DiTusa go back a long way, too: They co-trained Bumblebee’s grandson, David Jackson, who represented the United States at the 2000 Sydney Olympics, winning his first fight but failing to make weight for the second. Boxing aficionados consider Jackson among the most promising fighters the Pacific Northwest has ever seen, as well as one of its greater disappointments.

DiTusa and Bumblebee cackle over a memorable fight when Jackson first turned pro. “It was the Billy ‘the Kid’ Chapman fight,” says DiTusa. “Late in the second round, seconds from the bell, Jackson absolutely clubs Chapman. Chapman does a complete 180 into the ropes, out cold, propped up by the top rung. The bell rings. Chapman comes to, puts his glove to his ear like it was his cell phone, says ‘Hello! Who’s this?'”

Meanwhile, the kids can’t be contained any longer.

“Excuse me, I got to open the gym,” says Bumblebee. “Got to keep movin’; been paralyzed twice now, and if I stand too long in one place my feet don’t know what to do with themselves.”

With that, Bumblebee and his entourage burst through the Mission’s doors, striding down the hall as if approaching the ring for a title bout. The energy of the kids is palpable, as if one were bearing witness to an odd but hypnotic Pentecostal tent revival.

Kids buzz in and out of basketball courts and classrooms, one labeled The Joyful Noise Room. A 20-foot, floor-to-ceiling mural made of butcher paper has a picture of a giant headless Superman with a bold question mark where his head should be.

Below the cartoon hero is a quote from the prophet Isaiah: “It will be a sign and a witness to the Lord Almighty in the land of Egypt. When they cry out to the Lord he will send them a savior and depender and he will rescue them.”

We step inside the club. At first glance, the place seems little more than a large room with worn punching bags of all shapes and descriptions. Dozens of boxers young and not-so-young begin stretching, wrapping each other’s hands, and punching at shadows. Mats come out, towels get passed, and soon you hear the contrapuntal flick of jump ropes and speed bags making a soothing wockita-wockita sound. In the center of the room, an oversized bag dangles from a chain big enough to anchor a cruise ship. When the bag is struck solidly, the chain groans in appreciation.

In an annex adjacent to the gym is a tiny ring partitioned off by a see-through metal grate. Multicolored banners hang from the ceiling, and a deafening three-minute round timer goes off periodically, like a factory buzzer announcing a shift change.

The fighters pair up, one bruiser holding up mitts for a six-year-old Chinese girl, while another gets a 12-year-old to shift his weight fluidly, in one motion. Children with clipboards check the bulletin board religiously to make sure they follow Bumblebee’s Plan.

“Willi does this all as a volunteer,” DiTusa says. “Doesn’t take a dime.”

Hearing this, Bumblebee wobbles over, barking orders, taping knuckles, his smile pinched now and again by shooting pains. “Don’t take a dime? Sam, I get paid every day. These kids give out more than I could ever give back. I ain’t no saint, you know that. I got 20 living kids—10 boys and 10 girls by four marriages—but everybody knows who their daddy is. I do stay in touch.”

After the workout, DiTusa and Bumblebee finalize arrangements for a home in nearby Rainier Beach and a job in construction for the new fighter, Johnson. Bumblebee then pulls me aside and says, “You know how bumblebees are, when they’re all in a flower, why, they come so close, so very close together. Think of all that floating in perfect harmony, in the spirit. But you come along and disturb that flower, slap at them bees, and brother, you got Trouble with a capital T.”

Sam DiTusa defies—resents, actually—easy classification. Most of his free time is devoted to managing the careers of young professional fighters. In spare moments he serves as trainer and sometime mentor in places like the Bumblebee Boxing Club, helping to pull kids off the street.

A longtime correspondent for Fightnews.com, DiTusa is organizing his memories of working as a Seattle undercover vice cop into a book. The working title is 12 Years in the Sewer. He discusses how he cajoled prostitutes into rolling over on their pimps.

“So I get this woman in the car,” he begins. “She’s older. I say, ‘How much?’ She says, ‘100 bucks for sex, 50 for head, 20 for a hand job.'”

DiTusa looks down and sees that the woman has no fingers on her right hand. “How you gonna give me a hand job with no fingers?” he inquires.

“Everybody calls me Lefty,” she replies.

His negotiations with another hooker who was deaf and mute were crystal-clear. “I make a circle with thumb and use my forefinger, spread my hands palms up—how much? She raises two fingers and makes two consecutive circles with the other hand—200 bucks. I open my mouth wide, spread my hands, palms up—how much? She raises one forefinger [and] makes two consecutive circles with the other hand—100 bucks.

“Believe it or not, that was enough evidence.”

Other stories don’t provide such levity, like one involving his role in rescuing a 15-year-old girl from a deadly prostitution ring. “If you didn’t stay loose in vice, if you didn’t try to laugh every single day, pretty soon you’d start sobbing,” says DiTusa. “You see things no one should see.”

He quit vice one day, he says, “over what you might call a philosophical difference with a superior officer.” He laughs, looking skyward. “Now I cruise the mean old streets of Ballard and I love it.”

They called DiTusa “Popeye” as a kid because his forearms were the size of an average man’s biceps. To look Sam straight in the eye is to learn nothing at all. His gaze is implacable, but a sly smile meshes with his tone of voice, reassuring with an easy cadence, the words doled out with a storyteller’s ease.

A product of Chicago’s notorious west side, DiTusa is a second-generation Sicilian, and his eyes flash at any mention of Mafia ties. “I get bored with the question,” he says. “My family prided themselves at staying away from all that. My great-grandfather’s farm was near Corleone, where they filmed The Godfather. Big deal—you want good stories or true stories? OK, Gramps was an enforcer; he used a rusty double-barrel shotgun to guard his orchards and fields. Cosa Nostra or not, you didn’t go near the old man’s grapes or olive trees.”

DiTusa lived in the Melrose district, as Italian as neighborhoods get. His father was a typesetter for 38 years. After his mother, bedridden for the last 10 years of her life, died, Salvatore Sr. (Sam is Salvatore Jr. on his birth certificate) never dated another woman. He worked the famous Starlight Room as a bartender, sometimes hosting private parties for “guys who were connected,” says Sam, who insists his dad kept his distance. Salvatore didn’t want Sam to box, but Sam and his friends were loose cannons. His pals had names like Iggy and Joey the Bear and Dave “Iron Man” Kraal, so named because he once cold-cocked a card cheat twice his size with a steam iron.

Sam loved his father but was terrified of him. He gives an example: A carnival sets up shop in the neighborhood for a Catholic festival. (“Guys staggering around under floats of Mother Mary, the works,” says DiTusa.) His father prints up a couple dozen phony ride tickets so his sister could enjoy herself. She comes home bawling: One of the carnies confiscated the tickets. Still in his robe, Salvatore grabs his daughter’s hand, storms down to the carnival with blood in his eye, flattens a carny twice his size—Salvatore was only 5’6″—and walks home.

Says DiTusa: “The way he saw it, I guess, somebody made his little girl cry.”

DiTusa soon found his calling. There was a fight every week at the Boston Club, a walk-up bar in an ugly neighborhood with a huge ballroom on the floor above. A ring was set up there, and—voila—a fight club. DiTusa fought for peanuts, but the way he made folding money was by betting on himself. “I was a money fighter, made a few bucks, but risked unholy hell from the old man,” he says. “So I gave it up.”

He soon started working the Chicago docks unloading freight, a gig that lasted 11 years. In those days it was wide open, with “extracurricular” jobs that paid big dough. DiTusa declines to elaborate on what precisely those jobs were.

“That was the way it was back then; you did what you did,” he explains. “Let’s just say when I talk to kids on the streets, I know what the temptations are. Kids know you been there, sometimes they listen.”

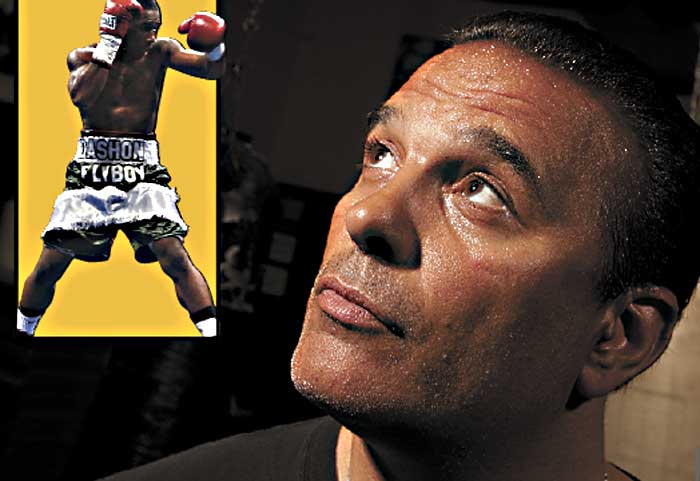

Dashon “Flyboy” Johnson, 21, had a bout in June at the Spirit Mountain Casino in Grand Ronde, Oregon. On paper it didn’t seem as if the welterweight would have a prayer against a fighter like Jason Papillion.

Johnson was a slow starter, his record 1-1-1 in his first three fights. In DiTusa’s hotel room prior to the fight, the 21-year-old was affable, soft-spoken—almost painfully polite. Under the tutelage of DiTusa and Kraal, who now trains fighters in California, he’d reeled off four straight wins to bolster his record to 6-2-2, but the competition was suspect.

Papillion’s record, meanwhile, at age 39, was 39-13-1, with 25 knockouts. He was once the USBA Junior Middleweight Champion, and had fought in Vegas against top-flight pugilists like Mark Suarez, Roman Karmazin, and Keith Holmes. Sitting ringside, Johnson seemed slight compared to the grizzled veteran.

The bell rings, and Johnson takes command of the center of the ring. It’s immediately obvious why DiTusa is high on his new charge. The kid has a jab so quick it’s blurry. But near the end of the first round, Papillion sidesteps Johnson’s volleys and wades in with ugly ferocity, throwing short, flat, sledgehammer punches that slam the kid back.

In the next round Papillion uses his experience on Johnson, trying every trick to lure him to the ropes. Recognizing this, DiTusa screams, “Stay off the ropes!” But Johnson, trapped, is tagged with a vicious left to the head. But then a light goes on—he somehow slithers underneath, sidesteps, counters with snake-tongue jabs, and returns to center ring.

The fifth round tells the tale. Papillion comes out breathing fire, forcing every issue, trying to bull his way through a hailstorm of combinations. But Johnson stands his ground, and then his overhand right catches the veteran flush on the proboscis, splattering blood and spittle across the shirts of those seated near the ring. Stunned, Papillion staggers, tries to cover up, and stumbles backward—but won’t go down.

Nevertheless, he never regains control of the fight, spending the last rounds head-hunting to no avail. Johnson is too patient, too quick, too talented. He ends up winning by majority decision.

Papillion bumps into DiTusa and Kraal at the airport on the way out of town. “When I seen your boy,” Papillion rasps, sotto voce, “I wanted to laugh in your sorry-ass face. But Jesus, what can I say? The kid beat my butt, whipped me. The kid has a future.”

That future comes despite a bleak past. Johnson has never seen a picture of his father, but recalls the parade of men who staggered in and out of his mother’s life. He remembers a Christmas, when he was 7, when a junkie slapped his mother, dragged her down the stairs by her hair, and threw the Christmas tree into the street, and with it his family’s presents.

“I saw too many crack pipes, too many knife fights and turf wars, saw a little kid in the wrong place get his head blown up like a pumpkin. I saw dead people as a child, stepped over them on the street. Kids shouldn’t see that,” says Johnson. “I had my heat inside, my rage. My older sister saved me, though, and somehow, some way, we made it through the day. I had sports. I always been quick. Boxing comes natural; it’s good to me. I treat it with proper respect. I do the work. Now, I got two fathers—Sam and Dave—when I had none. My demons are mostly dead or shriveled up. I’m very, very lucky. You understand?”

On July 31, DiTusa flies down to Pechanga Resort and Casino in Temecula, California, the mecca of professional boxing in that state. Johnson is fighting again, this time on the undercard of an event televised on Showtime. He’s fighting Alan Velasco, an ex-con with a 9-2-1 record who hails from Boyle Heights, a crime-riddled East L.A. neighborhood.

The bout would go well for Johnson. Wrote Patrick Gurczynski in the North County Times: “Not many people can overshadow Hall of Fame boxer Sugar Ray Leonard. Yet a relative unknown from Escondido did just that. When Dashon Johnson stopped Velasco in the second round, the roar from the crowd surpassed the decibel level of Leonard’s announced arrival.” (Leonard was introduced at center ring during the proceedings, and watched Johnson’s fight from the audience.)

“We were due to fight second,” recounts Kraal. “At the last minute, the promoters come up and pushed the fight to the back of the card, after the feature bouwt. I almost pulled Dashon, but he’s a push-button kid, a manager’s dream. He adjusts. If I asked DJ to mow my lawn he wouldn’t ask why, he’d just fire up the mower. I can’t tell you why he isn’t damaged goods. He has a flame inside. Rejection and childhood trauma can go either way. I was a ward of the state too. I know about rejection.”

“Velasco is a tough kid but he’s got slow hand speed, no focus,” he adds. “That Papillion fight was the nuts. There were only three people in that crowd thought we had a chance: me, Sam, and DJ.” Now Papillion’s going to get another title shot. That puts us in great shape.”

I meet with DiTusa one last time in Ballard. We cruise Market Street in squad car Two-Boy 23 in silence. After a while he says, “I owe Bumblebee. He’s a true friend to help with Dashon. Nothing in it for him.”

DiTusa pulls over. Words come in streams. He says 300 kids a week pass through the gym at the Mission, yet Bumblebee knows them all by name. DiTusa says he doesn’t get down there often enough, doesn’t bring his fighters down as much as he should. Sometimes he has motives. Talent comes through those doors, and fight managers need talent.

“Whaddya do for kids with no education, no apparent skills, no family life to speak of?” asks DiTusa. “We lose them every day. I spend my life doing what I can where I feel there’s need. For me it’s not complicated—it’s about connection, some inward place.”