PACIFIC NORTHWEST BALLET

Seattle Center Opera House, 292-ARTS, $15-$110. 7:30 p.m. Thurs.-Fri., 2 p.m. Sat., May 31-June 9

MOST OF US buy our clothes off the rack. We try to shop for a good fit and hope that the current styles coincide with what we’d like to be wearing, but made-to-order garments are usually reserved for people who sew or have large bank balances. That’s not the case with most dance companies, though. Revivals and restagings make up part of the usual repertory; the creative aspect of the director’s job is like choosing from an existing menu, trying to find something that fits the company’s tastes, skills, and budget. More frequently, work is made from scratch—dancers and choreographers meeting in the studio with little more than a few ideas and the willingness to work hard. There is a special excitement about a new work—a chance to see something made specifically for this time and these people—that can be like a custom-tailored jacket.

Choreographer Val Caniparoli has worked in both situations, restaging his existing work for companies around the world as well as creating new ballets. Although he’s entering his 30th year as a performer with the San Francisco Ballet, as a dancemaker he’s more of an itinerant. In the past couple of years he’s been to Singapore, Canada, Pennsylvania, and Colorado, as well as all over California, and now up to Seattle again. Caniparoli has been coming to the Pacific Northwest Ballet since 1984, when he made “Street Songs” to a charming score by Carl Orff. In 1997, he restaged “Lambarena” here, which very well might become his signature work.

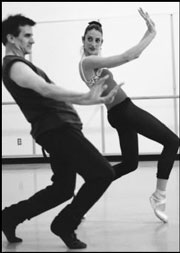

With its daring combination of classical ballet and African dance styles set to a score that alternates between Bach and African traditional music, “Lambarena” has been a hit wherever it’s been performed. Caniparoli admits that the work continues to influence his choreographic style, as he brings fluid torsos and shifting hips to a classical context. This is easy to see in “Torque,” his new work for the PNB: The 10-member cast propels itself through the space, riding on the momentum of the score by Michael Torke, digging into the ground as their upper bodies whip around, arms snaking close to the chest or slicing across the body.

Caniparoli has remarked that it’s actually easier to start with a restaging when he’s working with a company for the first time, preferring to spend his energy getting to know the performers rather than trying to fit new material to them right away. PNB is familiar territory for him, though, and he’s very complimentary when speaking about the willingness of its dancers and directors to take a chance on his work. Though he often creates narrative or emotionally evocative dances (such as “The Bridge,” made for the company’s anniversary season two years ago and based on a news report of young lovers killed in Bosnia), “Torque” is more abstract, taking its primary qualities from the score. Even in the obsessive repetition of rehearsals, it seems to fit the bodies of the cast well, as they stalk or cut through the space. Arianna Lallone and Olivier Wevers both use their length to great advantage, articulating the differences from standard ballet posture elegantly, but the whole cast seems to have picked up on the exciting dynamism of the work. In this choreographic equivalent of made-to-order couture, Caniparoli has proved to be an excellent tailor.