THERE ARE ALWAYS signs, but they aren’t always readable. Trevor Simpson, 16, was in a long funk—sleepless, and he had given away his favorite hat. Then the Edmonds-Woodway High School sophomore and football player drove his Chevy Nova to the lonely woods on the Tulalip reservation and hanged himself from a tree. He was always impetuous: With no rope, he dragged a set of jumper cables into the woods with him.

“We were really uneducated parents,” says Scot Simpson, 54, his dad. “I think you see in this room others like us—coming to grips with suicide, warning that it’s a true mental illness.”

At first on Sunday night, a few people trickled into the Wooden Boat Center on Lake Union to prepare for the sixth annual memorial Walk For Life, remembering the victims of suicide. Then a few more arrived. Suddenly it was 100—moms, dads, siblings, friends—a room filled with grief and grit. “It’s the club you wish you didn’t have to join,” says Sue Eastgard, state Youth Suicide Prevention Program leader who organized the event as part of national Suicide Prevention Week. “But someone dies from suicide every 17 minutes; about 30,000 a year.” And it hits brutally, with victim and killer one and the same in a death too often preventable.

Among the missed signs in Trevor Simpson’s life was attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. “We didn’t even know what that was,” says his father, “but we believe now that he had it. He was a loving kid. He got good grades but did poorly socially in school—he had this energy that would just get him into trouble. He slept anxiously, had nightmares, felt he was not treated fairly. What we know now we should have known then, and maybe he would still, you know. . . . “

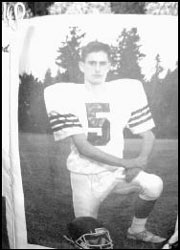

Several more times Simpson says, “We should have known”; there is a lot of self-blame in the room. Over by two death quilts on a wall, showing 80-some faces of mostly local boys and young men but also girls, mothers, and fathers who committed suicide, a woman dabbing her eyes tells another woman, “I just didn’t know what to do.” The picture of Trevor Simpson in his football uniform was displayed next to a man who was 54 and left behind a wife and six kids. Another man was 52—his wife of 27 years had cancer, he had lost his job, and four days before he killed himself, his daughter was reported missing. In almost all the pictures, the faces are smiling, and on the quilt, people have written “Sorry . . . if only we’d known. . . . ” There are few clues to what happened, although with one photo of a 45-year-old man named Sarge, there is a copy of his suicide note: “Mom. I am really sorry. This is not your fault. I failed. I wished I had never heard of cocaine.”

At least two other photos are of youths Trevor Simpson’s age, both in football uniforms. “That’s where I think he’d be today,” says father Scot. “Playing football—or, maybe, having played for the Huskies and graduated. He died in 1992, so he’d be 26 now. You know, he had a 3.9 grade average. He had figured it out, what his problems were, but he pushed it all inside himself. And we’d still see these outbreaks; he’d get mad for no reason, make impulsive decisions. We saw his anger but not his sorrow. There are drugs that can be used to help kids like him, but we didn’t know about them.”

After a while, the gathering moved to Seattle Center, the 100 marching along cold, windy streets carrying Walk For Life signs with the names of the dead. At the mostly deserted Center House, they took seats by the stage and listened to music and short speeches.

“Doctors say suicide is like a slot machine—all the numbers have to line up,” says Simpson. “Those numbers are represented by biological factors, psychological factors, and so on. You look for depression and take any talk of suicide seriously. After Trevor died, my wife went to the library and checked out books. We started talking to a lot of people, learning. Trevor’s school has a suicide-prevention club now, with 50 kids. It basically got started because of Trevor’s friends. His brother is active in it, too.” Simpson gave a hard smile. “Our family, I guess we’re experts now.”

Rick Anderson