Wayne Chow and Rod Richardson drove all the way up from Portland on Monday to stand outside in the kind of Seattle rain that feels like God is hawking loogies from on high.

Their purpose: give a pat on the back to Boeing machinists who rejected – decisively – a contract extension that would have guaranteed work at the expense of watered-down retirement benefits and more expensive health insurance.

“It was blackmail, an ultimatum,” said Richardson, a business representative with the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers Local 48. “That’s not negotiation. That’s not the way it works.”

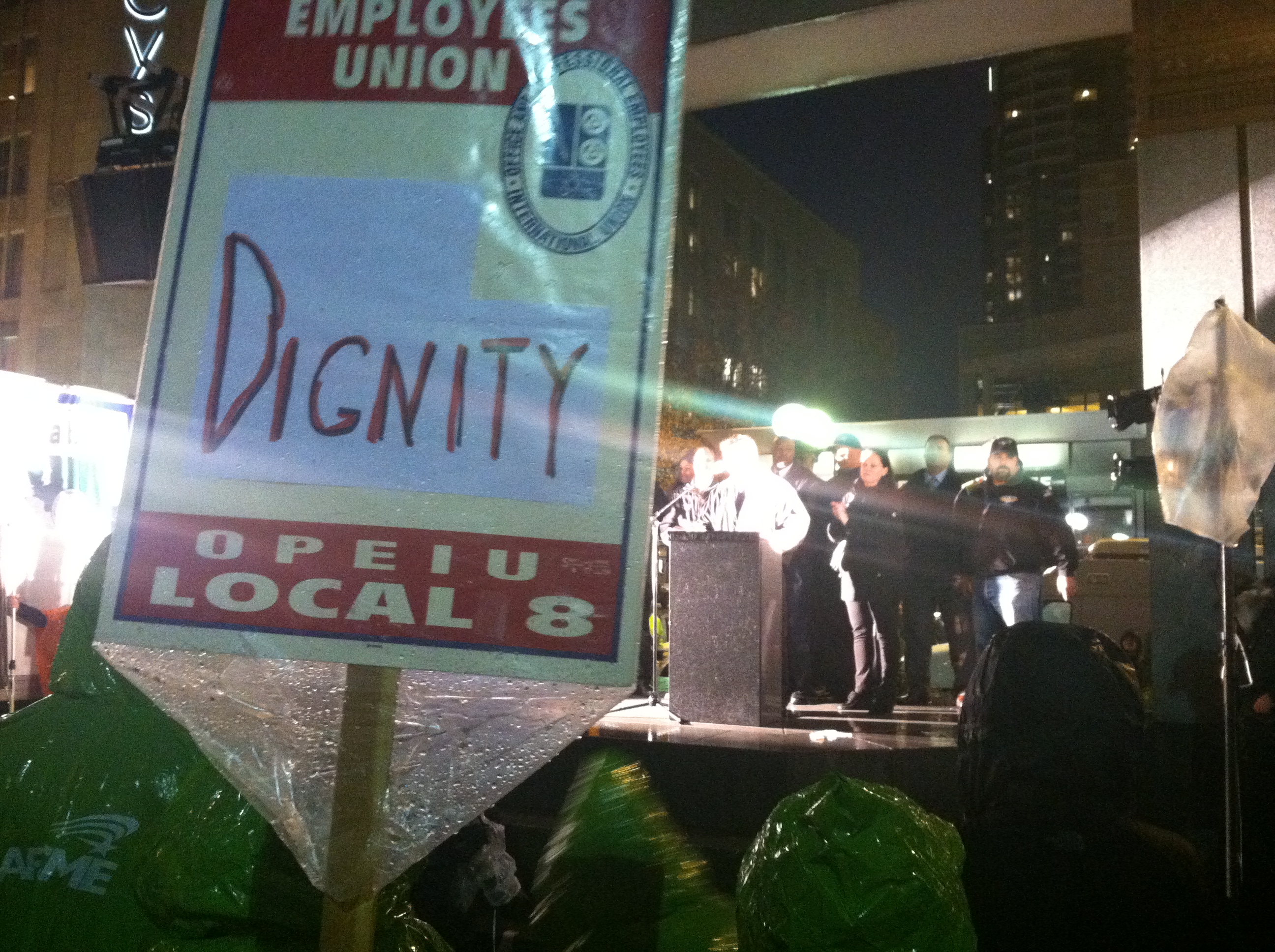

Wherever Boeing decides to build the next 777X, which management says will be announced within the next three months, the labor rally at Westlake Center Monday evening made clear that the machinists’ vote was a shot across the bow for labor. Perhaps a death throe as well, but no doubt a line drawn in the sand.

“They stood up for the middle class. They poured everything they had to make sure there is a middle class,” said a longshoreman who identified herself by pointing to the name embroidered into her jacket, “Deb.” “It’s going to get worse before it gets better.”

The rally in many ways felt like a dramatic climax to a year that heard the worker roar. In quick succession last week, the obscenely profitable Boeing demanded $9 billion in tax cuts and major concessions from the machinists union to guarantee it would build the 777X here. It was an act of corporate hubris that galvanized an already energized fight for labor and brought a degree a fury to Westlake Plaza unseen during previous rallies for higher minimum wages and against wage theft.

Jason Redrup, a union representative with the Machinists 751, said this about what seemed to be a mighty convergence of working-class unrest in Seattle: “What’s going on is Wall Street vs. Main Street. They have everyone convinced of this narrative that we have to accept lower wages and benefits and they can make record profits and we don’t any share in it.”

In a long roster of speakers, the woman who has best captured the zeitgeist of Seattle labor politics had the stones to call out the Democratic Party at a rally where the Democratic Party was hoisting very large signs.

“Are the two parties standing with us today?” asked Kshama Sawant, answered to a resounding “no,” a bad indicator for the standing of the Democratic Party with a labor force that makes up a major part of its base.

Ill-will was clearly felt toward the party’s standard bearer, Gov. Jay Inslee, for “capitulating” (Sawant’s word) to Boeing on the tax breaks. The thought at the rally was that by giving Boeing the tax breaks, it left the machinists alone to challenge the corporate giant.

“The politicians fucked these guys! They fucked them!” said one prominent attendant in private conversation near the stage.

There was also a real fear that the machinists, in the end, wouldn’t win this fight. More likely, a member of another union said, Wall Street would reward Boeing management for keeping labor costs down now, and by the time the 777X begins to be plagued with the problems that come with hiring a completely new work-force in a new state to build an airplane, “they would be retired.”

On the bus home, I found myself next to a machinist who had also just left the rally. He’d gotten off shift in Everett, taken a bus to Westlake, and was headed back home to Shoreline, his hair slick with cold rain. I floated the theory to him that management was immune to their decisions because Wall Street didn’t reward long-term thinking.

“Nobody in this country thinks 20 years down the line anymore,” I offered.

The machinist who had just voted down a contract, forgoing guaranteed work and a $10,000 bonus, in the hopes of a better retirement decades down the line, corrected me: “Some people do.”