They lined up down the stairs and out the doors, waiting patiently for the featured act. But it wasn’t a rock band the University of Washington’s law students came to see. It was rock stars of the legal world—a three-judge panel of the Federal 9th Circuit Court of Appeals from San Francisco—and they came to Seattle last Wednesday, April 6.

The “tour” is part of a program wherein 9th Circuit judges visit various West Coast law schools once a year to hear local cases and take questions afterward from eager students. Usually, the cases are fairly pedestrian. Not last week.

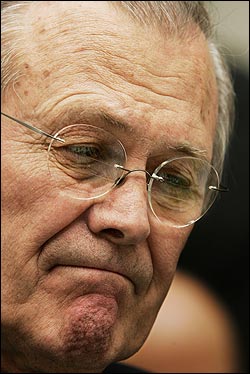

The attention was due to Emiliano Santiago v. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, the highest court test to date of the Pentagon’s controversial stop-loss program, aka the “backdoor draft.” (See “Stopping Stop-Loss,” March 30.) Under stop-loss, some 50,000 soldiers nationwide have been kept active involuntarily beyond the discharge date of their original contracts.

Santiago is a 26-year-old Oregon National Guardsman who works in Richland, Wash. He signed up as an 18-year-old high-school junior and was scheduled to be finished with his eight-year commitment last June, but two weeks before that date, his unit was notified of “possible mobilization.” Santiago was told at that time that he couldn’t be discharged—in fact, he was presented with a new contract with a discharge date of 2031, a potential lifetime of involuntary servitude. In October, his unit received notification of mobilization and began training for a mission to Afghanistan. To add further drama to last week’s court hearing, Santiago’s lawyers also wanted an emergency injunction because, barring court action, he was scheduled to ship out to Afghanistan in two days.

The Army allowed Santiago to fly up from Oklahoma, where his unit was training, to attend the hearing. He had already lost in lower courts, and his lawyers had tried and discarded a previous argument challenging the validity of the presidential declaration of a national emergency (which is the legal basis for stop-loss) as being moot now that Afghanistan has a democratic government. (Courts weren’t about to entertain the question of whether Afghanistan’s government was or wasn’t truly democratic.) This time, Santiago’s lead attorney, Steven Goldberg, tried to argue contract law—that without the backing of Congress, President Bush (with Rumsfeld acting as his agent) did not have the authority to unilaterally abrogate the terms of a contract with a soldier when a soldier is not already on active duty.

It was a long shot, reflected immediately in the aggressive oral questioning of Goldberg by presiding U.S. Circuit Judge Richard Tallman. Santiago, according to Tallman, was essentially asking the court to second-guess the commander in chief as to what constitutes a national emergency—something Tallman was clearly unwilling to do.

It was all over with remarkable speed: a mere 20 minutes for oral argument, and, within hours, the panel rendered a decision. Santiago not only failed to get an injunction to postpone his deployment, he lost his entire appeal—a process that usually takes weeks or months for a court to decide. Moreover, the full 9th Circuit in San Francisco declined to review the three-judge panel’s decision the following day. By Friday, April 8, Santiago was on his way to Afghanistan.

This exercise underscores how precarious the hope is, carried by many progressives, that the federal courts can be the last line of defense against a conservative White House and Congress. The appeals panel was there to decide a matter of law—not of politics or, for that matter, of common sense. At one point, Goldberg made the common-sense observation that giving the federal government unlimited power to extend tours of duty would make it that much harder to recruit volunteer soldiers, and Tallman responded, correctly, that that was the president’s problem, not the court’s. Courts are not, at least in theory, in the business of deciding political and legislative matters. It might be a matter of crass opportunism that Bush continues to renew declarations of a national “emergency” in the United States due to events in Afghanistan and Iraq, but it’s his call to make. And Congress is not about to make it more difficult for him.

In the classroom-turned-courtroom at the UW School of Law, all was proper decorum. But next door, in the overflow room, it was a grand old show, with students boisterously cheering and jeering the various verbal ripostes like some kind of reality-TV taping. It was real to tens of thousands of soldiers kept, many unwillingly, past the time they thought they’d agreed to serve. Some won’t survive that extra duty time.

It might not be fair. But, for now, it’s the law.