That moment when you’re futilely clawing at the boot pressed against your neck as your windpipe collapses may not be an opportune time to notice your own Sorel crushing another’s throat, but in today’s America it’s the ideal hour.

I’m reminded of that almost daily with this country’s limitless varieties of oppression: white over black, male over female, cisgender over non-conforming, rich over poor. All of them existing simultaneously, colliding, merging, morphing into new forms of perpetuating others.

Shouting your pain so people notice means you often find yourself hoarse and unable to lend voice to much else.

And yes, I know the word “intersectionality” has made its long progression to America’s buzzword pantheon … even Hillary Clinton used it. It describes the manifold and overlapping social miseries our country doles out depending on your gender, color, or class.

Ironically enough, it’s risen to the heights of our national lexicon at the same time we continue to decry “identity politics.” Roughly meaning, at least in colloquially, all political issues that do not revert to the mean – America’s so-called “common identity.”

The instant classic of an argument goes something like this: Instead of focusing on the anti-trans bathroom bills, or ravages of white supremacy, or those other pesky injustices of America, we need to uniformly focus on “our” collective economic fortunes — no matter how unequal those economic fortunes have stubbornly existed throughout history.

White working-class voters did not coalescence around Trump for emboldening racial indignance but because of “economic anxiety” – a memo mind-blowingly missed by the POC working class who turned out for his opponent. The rising tide of financial well-being will be high enough to cover all the other inequities, apparently. The unspoken oppression will be left to lurk just below surface level.

I was reminded of this looping narrative not a month ago, while standing in a coffeeshop line. A transgender woman, speaking about the murder of black transgender woman Brandi Seals, begin to sob uncontrollably ever so briefly.

“No one gives a fuck about us. No one cares,” she said.

It was impossible to argue. I’ve seen thousands march in this very city for straight cisgendered black males Che Taylor, Mike Brown, and countless others killed by police.

I’ve yet to witness those numbers for any of the 27 trans-gender people killed in 2017, nearly all people of color (a significant number black and Indigenous). It was the deadliest year on record for the transgender community.

Quite frankly, I can see how easy it is to feign concern with words, but be indifferent with actions at encountering the rash of hate crimes against the transgender community — even those committed in our very city.

Our innate American default is to be pre-occupied with the me: my pain, my hurt, my struggle, my life.

Rarely are we socialized to see how our pain, our hurt, our struggles, indirectly impair the lives of others.

It was an assessment I was challenged to make recently by community organizer Banaa Be.

Interviewing her for a forthcoming story, I asked her how it was possible for someone to simultaneously “chew gum and skip rope” at the same time in combating both toxic masculinity and anti-blackness concurrently.

Probing me as if Serena Williams just begged her advice on how to properly hit a forehand, she politely responded by saying I was better equipped to answer that question.

It was as humbling as it was a profound reminder. In my numerous screeds on the responsibility of society’s superfluously empowered and privileged to diminish their positions, I found myself overlooking my own status.

I reflected on a visit to an old family friend’s church nearly two years ago. The pastor preached that Black Lives Mattered. He led the all-black congregation in prayer for the families of those slain, whether in streets or crack houses. He appealed to God for mercy for their lives.

However, the “black lives” he exalted soon became clear.

This non-practicing agnostic fumed at the prayer for “those lost people” at the Pride Parade, gritting my teeth as the minister directed the congregation to sign I-1552 (a state bill that would’ve removed protections for transgender people in restrooms, locker rooms, and homeless shelters) as they filed out of service.

Never mind that transgender people are far more likely to be victims of bathroom attacks. Never mind they are disproportionately murdered as members of the black community. The black minister spun a yarn of fear featuring a transgender person preying upon an unassuming youth to justify his stance, met by a resounding chorus of amens.

At the time, I attempted to rationalize. I said nothing. I did nothing. I just darted through the door passed the petition, so I didn’t have to bother explaining why I would never sign such a hateful document.

It would have taken too much courage, too much defiance, too much disrespect of my elders and my heritage. That was my rationalization: I’d be betraying the community that welcomed me that day, and with it the fight for justice, and against terror, still raging in the black community. To point out that wrong is wrong, regardless of its perpetrator, would have “drawn desperately needed attention away from” that community’s struggle. As if a modicum of concern for the “oppressed, within the oppressed” couldn’t be spared.

As a straight cisgender male, I had nothing to lose, not really, in speaking up for those forced into silence.

As heavy as the boot you struggle against may be, its weight can be more than matched by your own squashing the lives underneath you.

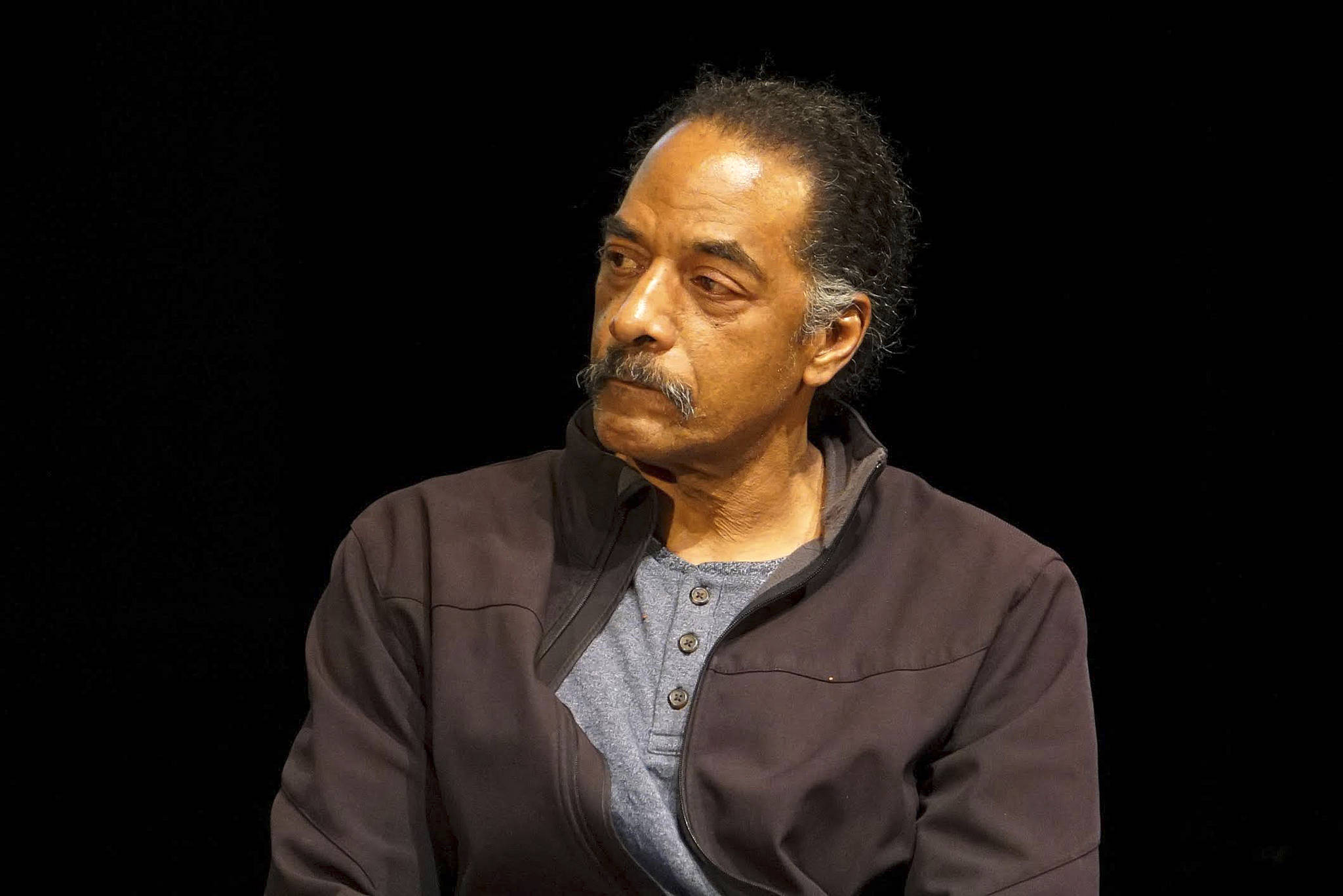

Marcus Harrison Green is the editor of the South Seattle Emerald. His column appears in Seattle Weekly the last Wednesday of every month.