On March 10, lawmakers passed a bipartisan bill aimed at salvaging the 2012 charter-school law that the state Supreme Court struck down in September.

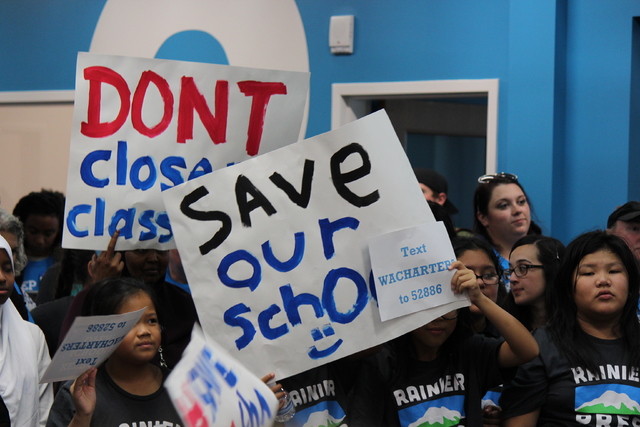

If Governor Jay Inslee signs SB 6194, it will, with a few amendments and caveats, essentially reinstate the 2012 law — a thrilling denouement from the point of view of charter school supporters, who’ve been pouring hundreds of hours and millions of dollars into propping up existing charters and lobbying the legislature to override the Court’s ruling, from TV ads sponsored by the Washington Policy Center to busloads of schoolkids and parents consistently filling the hallways, hearing rooms, and front steps of the Capitol Building.

“Obviously we’re not across the finish line yet,” says Washington State Charter Schools Association CEO Thomas Franta. “We’re still waiting on the Governor’s signature.” But, he says, “We feel really good. It was fantastic to sit and watch the House and Senate deliberate on these issues — [on] what I believe was a cordial debate about the merits of charter schools. And those that are on what I believe is the right side of history won out.”

The bill would provide funding for charters through state lottery proceeds, instead of the general fund — specifically, the Opportunity Pathways account, a part of the state treasury that offers educational grants and scholarships — and would prohibit charters from receiving any dollars from local school levies. It would add elected officials from the State Board of Education and the Office of the Superintendent of Public Instruction to the appointed Charter School Commission. And it wouldn’t allow traditional public schools to convert to charter schools, which Franta sees as a “pretty critical loss,” although in general, he believes that every amendment added to the bill “added something valuable. What those amendments did [was] increase accountability and increase transparency.”

Meanwhile, many public education advocates are tearing their hair: There is a real possibility that charter schools will get their funding in the next academic year, while traditional public schools will remain unconstitutionally underfunded. SB 6195, which Governor Inslee signed on February 29, does little more than outline a plan to make a plan to fund basic education during the 2017 legislative session.

“We continue to oppose charter school legislation,” says Rich Wood, spokesman for the Washington Education Association, the state’s largest teachers’ union and one of the plaintiffs in the case that challenged the charter-school law, “especially at a time when the state legislature is violating the constitutional rights of 1.1 million Washington school children by not fully funding the K-12 public schools as required by the state constitution and the McCleary decision,” he says. “You have to look at it in that context.”

Indeed, the numbers are stark: Traditional public schools serve 1.1 million students; charter schools currently serve 1,100. “The legislature spent time trying to fix a flawed, unconstitutional charter school law,” says Wood. “Yet it is failing to fully fund public education for all of our kids. From the perspective of students and teachers and school employees, it doesn’t make any sense.”

Regardless of one’s take on the charter school issue, though, some lawmakers don’t believe the bill is a fix at all. It’s possible that it does not resolve the constitutional arguments that crumpled the law in the first place.

“I think we’re going to be right back where we started from,” says Rep. Patty Kuderer (D-Clyde Hill), who voted against the bill. While the Washington Education Association and other former plaintiffs have not yet affirmed this publicly, Kuderer believes that sooner or later, we’re going to see another lawsuit. “And I’m not surprised,” she says, “given that I think there is vulnerability in the way this is funded.”

If and when the charter school system expands, she argues, lottery proceeds in the state’s Opportunity Pathways account may not be enough to support both a charter school system and the grants historically offered through that account. As a result, “The funding issue is still alive and well, unfortunately.”

She also sees constitutional flaws in the bill’s “failure to provide elected oversight” for charter schools, which would still be predominantly authorized by a set of appointed Commissioners, instead of elected officials.

For these reasons, the bill does not pass “the smell test,” Kuderer says.

Still, she did vote for an amendment that would have kept the state’s eight existing charters alive, without providing funding for new ones. “I wanted to keep the ones that were open, open. I wanted to save those schools,” she says. This version of the bill, though, strikes her as giving even those eight schools “an uncertain fix.”

Since the Supreme Court upheld its ruling last fall, the state’s charters have put together a couple of stop-gap measures — two schools opted to become homeschool centers, which means they receive no state dollars right now, and the other six partnered with the Mary Walker School District, in Springdale, to become Alternative Learning Experiences — another special kind of publicly-funded educational program that school districts typically use to offer distance learning or online coursework. (Notably, the Mary Walker School District received a $2.1 million grant for “collaborative partnerships” in December 2015 from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, long a major supporter of charter schools.)

To Thomas Franta, the charter school bill “is the long-term fix we’ve been advocating for for the last six months.”

But to Rep. Kuderer, “If the charter school folks would like to have a bullet-proof way to establish them, it would be to amend the constitution.” This bill, she says, “is a false promise to the families of charter school kids.”

And if some people feel frustrated by the charter bill’s passage, given legislative inaction regarding the McCleary decision? “I think they have a right to, to be honest,” she says. “I would have liked to have done a lot more than vote for a plan for a plan.”

Washington’s constitution calls funding basic education “the paramount duty” of the state, she adds. And so far, “we have not fulfilled our duty.”

Sara Bernard writes about environment and education, among other things, for Seattle Weekly. She can be reached at sbernard@seattleweekly.com or 206-467-4370. Follow her on Twitter at @saralacy. Get more from your favorite writers by subscribing to our weekly newsletters.