It was the energy and conviviality of live events that originally drew Seattle native Kyle Daley to transform sleepy towns and empty venues into theatrical spectacles. Over nearly a decade, the 31-year-old Daley has worked as a rigger at venues up and down Washington, from Seattle’s CenturyLink Field and Safeco Field to the Tacoma Dome and the Gorge Amphitheatre in George. Every day looks different for Daley, who juggles gigs ranging from setting up lights to pulling hundreds of pounds’ worth of equipment into the air to hang speaker clusters over stages. Although the work is physically demanding with unpredictable hours, he finds it deeply satisfying.

“We love the music, we love the community of live events, theaters, and concerts,” Daley says. “We want to be part of it.”

But with his commitment to the job comes the double-edged sword of work instability and ever-present safety concerns. The riggers have also been asked by employer Rhino Staging to work full days without taking state law–mandated breaks, he says. “The whole business model of Rhino is to bring in new people, give them as little training as possible so they can keep their rates down,” Daley says. The hiring and scheduling practices seem arbitrary to him: “They basically churn them and burn them.”

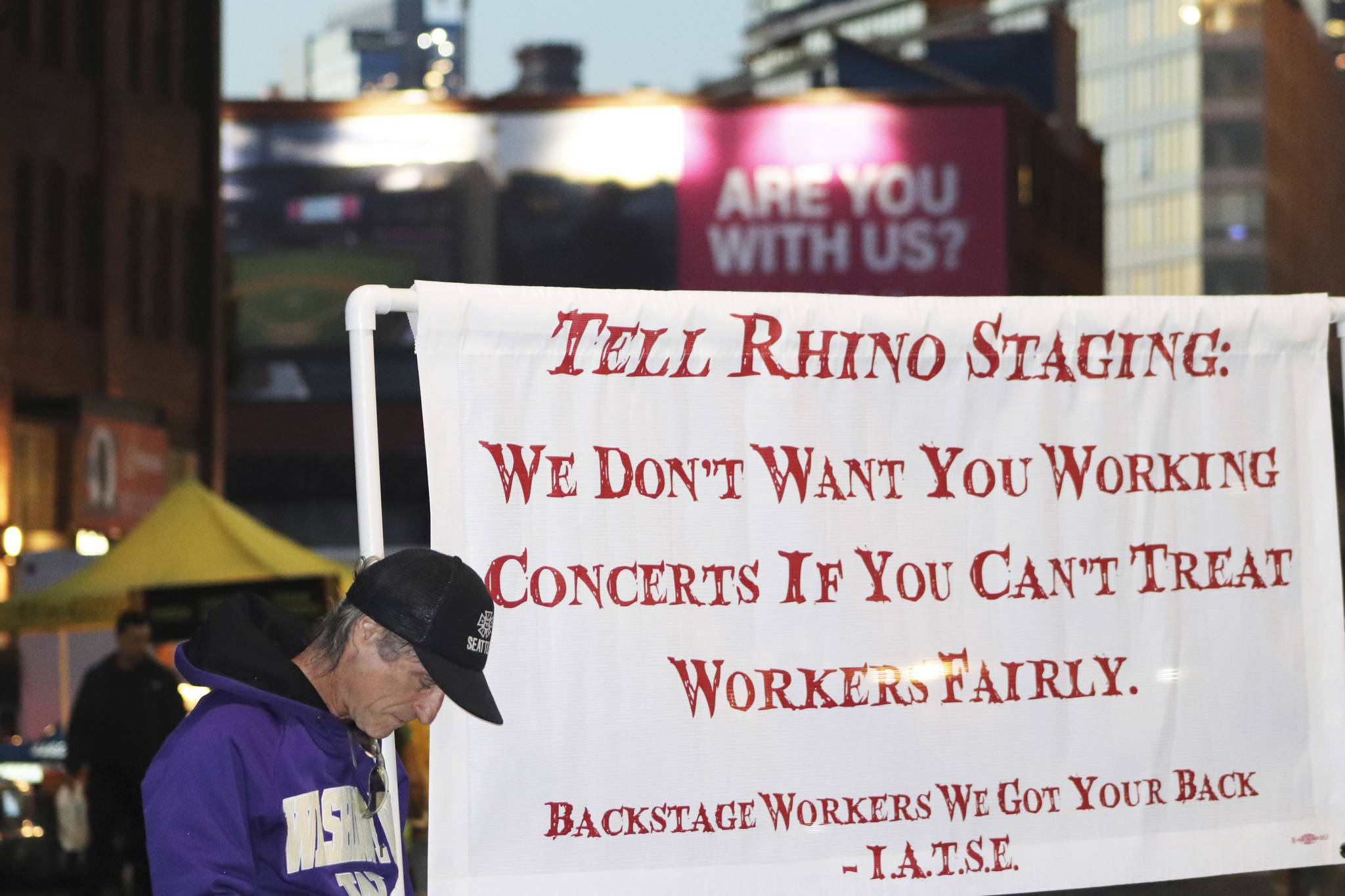

In an effort to gain greater protections backstage, Daley was one of 70 riggers and stagehands employed by the Arizona-based event-management company who voted to unionize in 2015. The regional chapter of the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees (IATSE Local 15) is currently at a standstill in contract negotiations with Rhino Staging that began earlier this year. In response, riggers have emerged from behind the stage to protest outside Washington concert venues this fall, with their next action planned for Nov. 17 outside of the Tacoma Dome at Fleetwood Mac’s concert.

The concerns from stagehands and riggers about the proposed contract with Rhino include lack of retirement and health benefits, job instability, and low wages. Daley says he works anywhere from four to 60 hours a week depending on the gig; moreover, after eight years of work, he makes $32 an hour as a head rigger, compared to union members with the same position in Portland who earn over $40, according to IATSE.

Safety is often at the forefront of their minds as the riggers precariously walk on beams dozens of feet in the air. Yet, Daley says, most new arrivals are not properly trained before they are put in dangerous situations. For instance, he says he has sometimes been stationed at great heights with another worker who has not been trained to perform a rescue if one of them were to fall. “I’ve seen and I’ve heard of a lot of people getting hurt on the job. It’s very much an aspect of what we do,” he says. Precautions are also on the shoulders of the gig workers who are already scraping by, he notes. Riggers are expected to pay upward of $300 for their own safety equipment, otherwise management may not ask them to return to future gigs if they continue borrowing Rhino’s gear, Daley says.

Daley’s concern about the daily danger he faces isn’t unfounded: In May 2009, a Rhino rigger died after falling nearly 40 feet to the stage floor following a Tom Jones performance in Las Vegas. The inexperienced rigger had incorrectly worn his safety harness, calling into question the precautions in place for workers at the Las Vegas Strip. The Nevada Occupational Health and Safety Administration blamed Rhino Las Vegas and the hotel where deceased rigger Vicente Rodriguez worked for violating safety standards. In the end, Rhino paid $4,000 in a settlement, according to the Associated Press.

But settlements are not always guaranteed, and union members said that they fear retaliation if they speak up about safety concerns. “If you happen to complain about your working conditions, or ask for more money, or in any way aggravate your supervisors, it’s not uncommon for Rhino to just simply stop calling certain individuals, and thereby deprive them of a significant portion of their income,” says Daniel Di Tolla, IATSE international vice president. Di Tolla says the beleaguered contract-negotiation process with Rhino Northwest is unusual, as employers customarily allow union members to successfully negotiate a collective-bargaining agreement without inserting roadblocks. “This particular instance is really an outlier in that Rhino just refused to bargain substantively, and has engaged in the most dilatory practices in order to avoid bargaining.”

Daley would like to see greater safety training, along with guarantees for work stability and benefits, all of which he says is not in the proposed contract: “We’re not able to make ends meet in this marketplace.”

Rhino Staging did not answer specific questions about the collective-bargaining agreement, but stated in an email to Seattle Weekly that the company was engaged in a good-faith effort to negotiate a contract with workers. “We are committed to competitive, market-based wages and the highest safety standards in our industry,” wrote Rhino Staging CEO Jeff Giek. “Regarding our commitment to safety, we recently revised our policy to require all employees to wear steel-toed boots for all tasks. The union opposes the new policy and has filed legal charges against us for implementing a safety rule that is clearly intended to protect our employees.”

However, the IATSE representative leading the Rhino riggers’ bargaining team, Chris “Radar” Bateman, wrote in an email to Seattle Weekly that the workers would need to buy their own shoes, and that Rhino’s promises only skim the surface. “The union is not opposed to steel-toed boots where there is a danger of foot injuries, but there are problems for riggers working far above the stage walking on narrow beams. It’s an illusion of safety,” Bateman wrote. “It was recently described by one rigger as ‘trying to run a marathon in flippers.’ It may lead to falls. Perhaps more importantly, the union is trying to negotiate a comprehensive safety policy. This is one unilateral change made by management and violates labor laws.”

In the meantime, IATSE Local 15 members will hold protests at concerts until they’ve received a contract. Several union members held banners that read “Stand With Rhino Workers” on Nov. 1 outside of the Tacoma Dome during Drake’s concert. The Canadian singer did not respond to a letter that the union members sent before the event, but IATSE Local 15 is determined to reach other entertainers who perform at the venues where Rhino workers are staffed. Union members also sent letters to Fleetwood Mac, Beyonce, and Justin Timberlake—before his Nov. 12–13 shows at the Tacoma Dome were postponed—although they have not yet received responses from those entertainers.

Elected officials, on the other hand, have penned support for Rhino workers in recent letters forwarded to the union. Seattle City Councilmember Teresa Mosqueda sent a letter to the union that called for increased safety protections and health care for backstage artists. “Seattle is going through an unprecedented population boom as more and more people come to live and work in our great city. But, as our population grows, we must make sure that our workers aren’t left behind,” Mosqueda wrote. “I fully support workers unionizing, having a voice and dignity. I also support backstage artists earning a living wage, having access to affordable family health care, and ensuring that safety precautions, equipment, and training are provided.”

City of Tacoma Deputy Mayor Anders Ibsen also sent a missive to Rhino Staging Northwest encouraging the company to continue negotiating a contract with union members. “As our economy continues to grow, I want to ensure that none of the hard-working people who make concerts and other events happen are left behind, and that they have access to just wages, health care, and better safety protections,” Ibsen wrote. “I hope you will continue to bargain with IATSE in good faith to ensure your most valuable asset, your workers, have the resources necessary to do their best work with dignity.”

The union has also generated a Care2 petition imploring concertgoers to boycott Rhino Staging until the company negotiates a contract with the workers. The petition has received over 7,000 signatures. Union members plan to pass out flyers to inform concertgoers of the conditions backstage during the upcoming Fleetwood Mac show in the hope that pressure on Rhino will help them receive the benefits and compensation they believe they deserve.

More than anything, Daley would like concertgoers to have a deeper understanding of the experiences invisible to them as they settle into their chairs before a show. “Workers all over this region are getting screwed,” he says. “We’re out here doing our thing, and we just want people to know what’s going on on our side, and for people to think ethically about their concert experience.”