Peer through a timescope and the Seattle of the early ’80s can seem nearly as quaint as the frontier outpost that the Dennys, Yesler, and Doc Maynard built. Traffic moved, even on I-5. Newspapers were vital institutions, ardently cherished or loathed, and the hottest issue was whether Seattle’s two dailies should be allowed to merge their advertising, circulation, and business operations. Geoducks were cheap chowder fodder—50 cents a pound in the Market—not pricey prizes for flagrant diners in Tokyo and Shanghai.

Bistros and condos had just begun to displace the Cinderella Liberty peepshows, sailors’ bars, and SROs along First Avenue. Broadway had fern bars; Pike-Pine (which wasn’t called “Pike-Pine” yet) had garages, sign shops, and a few inconspicuous gay bars. Outside of a roadhouse or two on outer Aurora Avenue, the nightlife was at Pioneer Square, which was fashionably restored but still had cheap lofts for artists.

West Seattle and Ballard were Twilight Zone time bubbles, sleepy holdouts from the 1950s. You didn’t have to be Scandinavian to live in Ballard, but odds were good that you were. “Snoose Junction” had Danish and Swedish restaurants but no Thai, Vietnamese, Japanese, or even Mexican. Craft brewing arrived with Redhook in mid-1982, but you couldn’t get a pint, or espresso, atop Queen Anne until years later.

Perhaps it was atavistic Scandinavian modesty that made 1980s Seattleites suspicious of fashion and slow to adopt new styles and indulgences. Again and again locals would pretend to lament the fact that their town was “five years behind New York.” Or was that five years behind Los Angeles and 10 behind New York?

“Is Seattle a Company Town?” one Weekly cover asked, beside a photo of a jetliner. People still bristled rather than laughed at the suggestion, one sign that Seattle was indeed Boeing’s company town. If you didn’t work at the Lazy B, you knew several people who did—or relatives, if you grew up around here; 1980 was the last year that more Seattleites were born in Washington than in the other 49 states.

By then Boeing had recovered from the 1969–71 bust that gave Seattle its own private depression. But the memory lingered, instilling contradictory feelings of relief and diminished expectations. Houses that had sold as HUD repos for $10,000 in the early ’70s now went for $50-, $60-, even $100,000. How could they ever go higher?

While Ronald Reagan was pulling the GOP and the country to the right, Seattle still sent a few moderate Republicans to Congress and Olympia. Among them was the crooning governor, ex-King County executive John Spellman—the last Republican to occupy the governor’s mansion. The city turned decisively blue after that, and the state eventually followed.

Seattle voters were either better served or more forgiving then. Since the turn of the millennium, they’ve voted three mayors in succession out of office. In the 1980s they kept Charley Royer, a dapper ex-TV commentator and political neophyte, until, after three relatively untroubled terms, he’d had enough and decamped to Harvard.

The police enjoyed a benign reputation, to a fault. They seemed impotent to stem the infiltration of Los Angeles’s Crips and Bloods and, at the decade’s end, crack cocaine into the homegrown gang infrastructure. The violence that drove the headlines was committed not by hair-trigger cops but by serial and mass murderers; the bloody late-’70s sprees of Ted Bundy and “Hillside Strangler” Kenneth Bianchi (who committed his last murders in Bellingham) were still fresh in memory. The then-faceless Green River Killer was scattering corpses—more than any other serial killer in American history—across South King County. Three young robbers gunned down 14 victims at the Wah Mee gambling club in Chinatown, Washington’s worst mass murder.

Amateur criminologists from here to The New York Times speculated about the dark, dank climate that supposedly bred a Northwest strain of shadowy violence, or at least provided a suitable backdrop. Fiction and film followed the trail. “Northwest noir” reached a peak at decade’s end when David Lynch came here to film Twin Peaks. Twenty-one years later, The Killing continued the tradition—except that by then, Vancouver typically stood in for Seattle, just as Seattle had once stood in for San Francisco.

Northwest noir music—grunge—grew out of the soil of punk in the late ’80s and would eventually make Seattle a pop-music mecca. Northwest noir movies—Trouble in Mind, House of Games, American Heart and its documentary companion film Streetwise—echoed the perception of danger and decay that haunted downtown Seattle in the 1980s. Not that all was rosy. The digging of the downtown bus tunnel hollowed out Third Avenue figuratively as well as literally. Businesses struggled and shuttered. Shoppers fled to the malls as a scruffier, poorer, sometimes rougher crowd trickled up from Pioneer Square and the old sex-and-drug peddling strips along Yesler Way and Jackson Street.

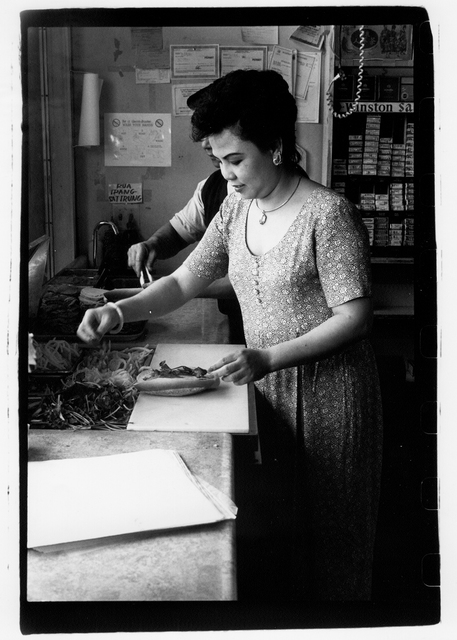

The street trade along Jackson was replaced by shops and restaurants of Hieu Saigon, Seattle’s new Little Saigon. The flood of Vietnamese boat people and their Hmong, Mien, and Khmer counterparts in the early ’80s was just the first of many refugee waves—from East Africa, Central America, the former Soviet Union, even hermitic Bhutan and Myanmar—that would enrich local culture (and dining), invigorate ailing neighborhoods, and challenge schools and social services.

Downtown, however, department store owners and other downtown boosters feared a ghost town in the making and pushed for concessions from politicians. Populists and public-space advocates pushed back.

Ground zero in their battle was a pie-slice-shaped pair of blocks at the top of Westlake Avenue. Royer won the mayor’s office in 1977 by urging a public space—art museum and park—at Westlake. His opponent, community development director Paul Schell, backed a hotel/retail complex. But the art-museum plan collapsed and commerce—a Rouse shopping mall and office tower—won. Thus was planted the seed of the 1990s “downtown renaissance” led by Niketown and a slew of other national mall brands, which left the shopping district glitzier, busier, and economically healthier—but also more generic.

Likewise, what’s now called the downtown transit tunnel laid the tracks, literally, for the light-rail system now being built out. Metro cannily secured funding for a bus tunnel from the bus-friendly, rail-loathing Reagan administration, then laid tracks down it for future trains. Those botched tracks had to be torn up and replaced, but Seattle had crossed its transit Rubicon.

The event that would most transform Seattle in the 1980s and the decades to come had passed unheralded the year before. In January 1979, two college dropouts from Seattle moved their little software company from Albuquerque to Bellevue. The Weekly did take note the next year when Bill Gates and Paul Allen signed a contract to develop an operating system for IBM. The train had left the station.

Six years later Microsoft went public, creating a new class of youthful stock-option millionaires. Their ranks swelled over the next two decades, and their influence spread like a slow-motion tsunami, transforming economy, culture, and philanthropy alike as they started new businesses and charities or invested in old ones. From the Gates Foundation and its research satellites to the Seattle Theater Group and the restored Paramount Theater; from the glittering Eastside to towering South Lake Union (courtesy of Allen’s Vulcan); from mayfly tech startups to megasaurus Amazon—all flow from Gates’ and Allen’s unheralded return home.

In 1994, the pool of programming talent around Microsoft drew Jeff Bezos and his Big Idea. Bezos knew in whose tracks he was following. The year after Amazon.com went live, an East Coast magazine sent me to write a squib about this new company that was—who would have thought?—selling books on the Internet! Bezos gave me the tour, then stopped in the main computer room. “Let’s see what [Nathan] Myhrvold is reading!” he said with the impish glee of a kid spying on his elders, and we scanned the shopping list of Microsoft’s chief technology officer. (Lots of paleontology books.)

The impact of Bezos’ gambit, like

The effects of Gates’ and Allen’s return home only became apparent years later. Each subsequent boom has brought a louder chorus of complaint about torturous traffic, nosebleed house prices, shallow digital consumerism, fading local character, and yawning inequality between the real-estate and tech-job haves and everyone else. Each chorus is timely, but all are still singing to music that was written in the unassuming ’80s.

Eric Scigliano served as a staff writer and in various editorial positions at Seattle Weekly from 1982 to 2000.