This afternoon, Mayor Ed Murray transmitted to the city council his proposed legislation for reforming the Seattle Police Department. The legislation, which Murray called “perhaps the most important piece of legislation during my time in office,” is part of the federal consent decree that Seattle entered in 2012 after a damning Department of Justice investigation found excessive force and possible racial bias in the department.

“For the first time in our city’s history, there will be strong civilian oversight of the Seattle Police Department, including an independent Inspector General, a stronger Office of Police Accountability and a Community Police Commission,” said Mayor Murray in a press release. “Change does not occur overnight, which is why we’ve been engaged for months – years since the beginning of the Consent Decree – to ensure we get police reform right.”

In general, the reforms aim at putting civilians, rather than sworn police officers, in charge of monitoring Seattle police. As proposed by the mayor, the legislation creates a new Office of the Inspector General to investigate systemic problems of abuse and accountability in police and other city departments. The already-established Office of Professional Accountability will be folded into a new Office of the Inspector General, where it will continue investigating complaints about individual officers, but with a mix of police and civilian investigators rather than having cops investigate cops, as happens currently. In addition to supervising OPA, the Inspector General will have a broad mandate to investigate systemic problems, and will have the power to subpeona and compel police officers and other witnesses to cooperate with an investigation. The Inspector General can only be fired for cause and with a majority of council’s approval.

The legislation makes the Community Police Commission permanent, and puts one of the CPC co-chairs on the search committee which chooses the Inspector General. The OPA, CPC and Inspector General will all have authority to formally recommend changes in SPD policy; SPD must respond to any recommendation within 30 days with either a plan for implementing the recommendations or an explanation for why they are rejecting the recommendations. In other words, under the legislation, Seattle police are not required to accept any recommendations, but they cannot ignore them. At a press conference this afternoon, Mayor Murray promised that as long as he’s in office he will order the chief of police to accept and implement all recommendations, unless there is a legal reason not to such as violating laws or collective bargaining.

The legislation also gets rid of the Disciplinary Review Board, which has the power to overrule disciplinary actions against officers. The DRB has been heavily criticized in the past for giving misbehaved cops a pass, since two of the three members are police officers. Instead of the DRB, all appeals of individual disciplinary actions will go to the Public Safety Civil Service Commission, which includes no police. Two members will be appointed by the mayor and one by the council.

The mayor’s office estimates that Seattle could be in “initial compliance” with the consent decree by early fall this year, though there will be a two year probation period before the consent decree and federal monitoring goes away. Many of the recommendations still need to be approved by the police unions (the Seattle Police Officers Guild for rank-and-file and the Seattle Police Management Association for higher-level officers) in contract negotiation. It’s possible that the unions could resist some of the changes, but the federal judge overseeing the consent decree has threatened to overrule the contract negotiating process if the unions dig in their heels. According to the mayor’s office, the police unions are already appraised of the details of the proposed legislation. The legislation does not make police union negotiations public.

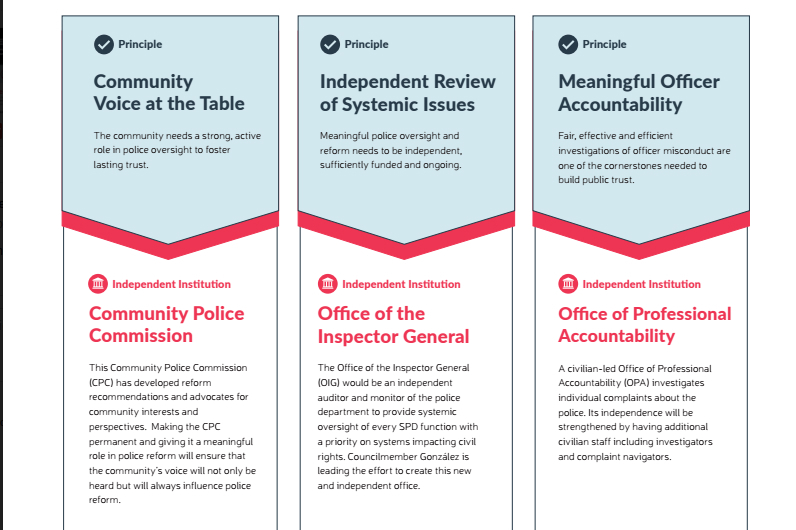

“As the mayor often says, it is the council’s job to improve legislation,” said councilmember M. Lorena González at the press conference, “and that is what we intend to do.” González’s Gender Equity, Safe Communities and New Americans (GESCNA) committee will review and probably amend the legislation over the course of seven public meetings, including two dedicated to public comment. González’s office has produced this infographic explaining the principles and timeline of the accountability legislation. You can see a detailed schedule for the legislation here, with a final council vote expected in May .

Representatives of the CPC said they are on board with much of the legislation but also have some disagreements they plan to hash out when council reviews it. One, according to CPC member Lisa Daugaard, is insulating the Inspector General’s budget from political pressure. The CPC wants the Inspector General’s budget to be a fixed percentage of the overall police department budget, while the mayor’s office wants them to be seperate. “We are not proposing a dedicated revenue source” per se, said Daugaard. “We understand that SPD’s budget is going to go up and down in hard times and good times. When it goes up, so should the budget for the civilian oversight entities.

“These are people whose job it is to be critical of a mayoral appointee,” said Daugaard. “Inherently, there’s a sense of ‘I want to keep my house, I want to keep my kids in school, maybe I should pull punches.’ So we need to protect people in those positions from the tendency to self-edit and self-censor, [in case] they feel their jobs or their budgets are vulnerable to blowback if they say what they need to be saying.”

CJaywork@SeattleWeekly.com

An earlier version of this article incorrectly identified Lisa Daugaard as a co-chair of the CPC. She is a member and former co-chair. A caveat has been added to Mayor Murray’s promise to implement all reform recommendations.