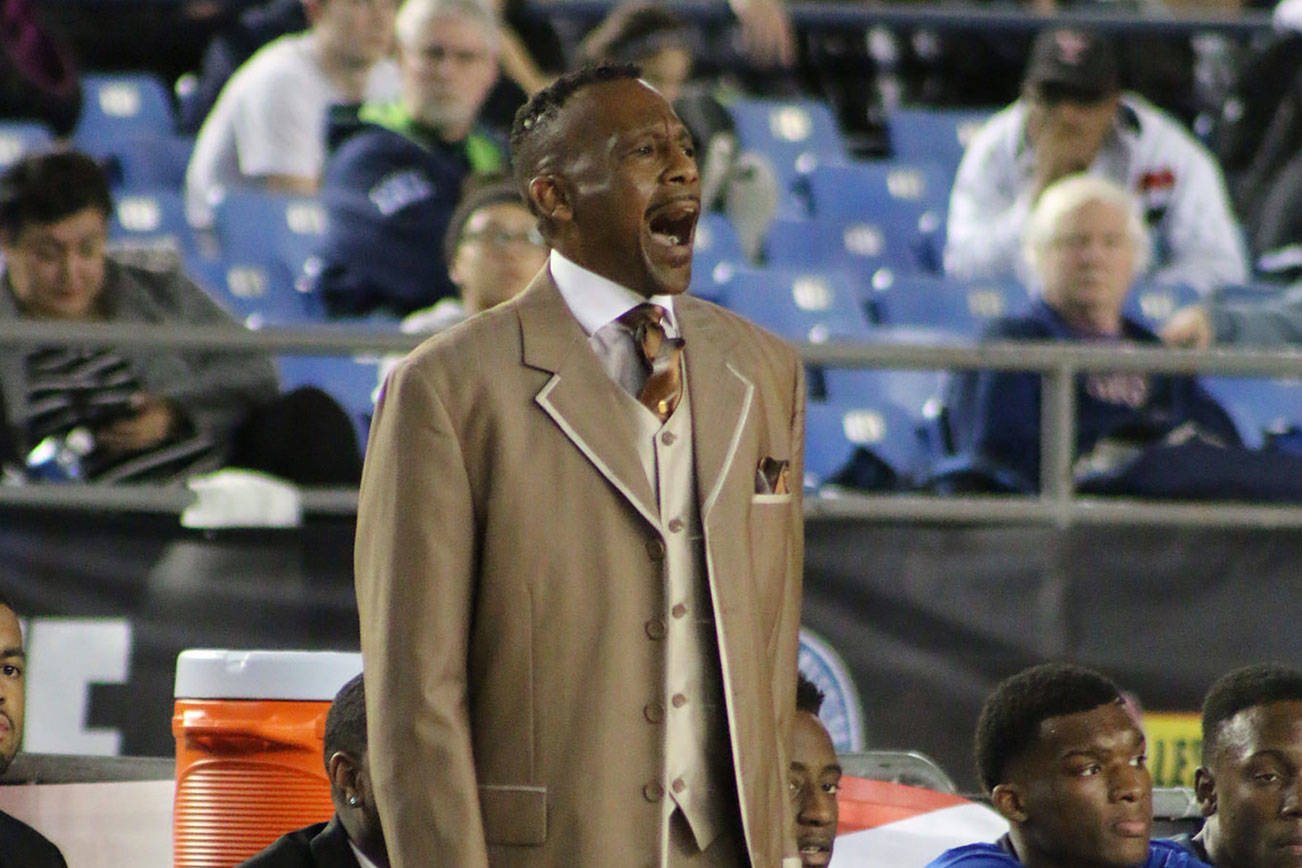

King County Assessor John Wilson is not the elected official who typically comes to mind when one thinks of local affordable-housing advocates.

The assessor’s primary job is identifying and assessing the value of taxable property. But housing advocacy is what he’s engaged in—at least when it comes to modular housing construction on publicly owned land to help battle the regional affordability crisis.

“We have the land,” Wilson said Aug. 13 in his seventh floor office in the King County Administration Building in downtown Seattle. “The question is do we have the will to truly work as one region and move on this?”

The idea of using publicly owned land for affordable-housing development is not new. The notion always gets brought at election-season candidate forums, and at times the theoretical policy tool has united the unlikeliest of allies, such as socialist Seattle City Councilmember Kshama Sawant and for-profit developers, who both have endorsed the proposal in the past.

But the prospect of building affordable housing on surplus public property has been stymied by a previously longstanding state law that required local governments to sell unused land at full market value. This law made it more difficult for nonprofit affordable-housing developers—the organizations that build and operate much of the regional affordable-housing stock—to acquire land for development, especially since land values in the Puget Sound region have skyrocketed. “Clearly part of the problem that we’ve had building enough affordable housing is simply the price of land in the city in particular, but also anywhere in proximity in the county,” Wilson said. “Land’s become so expensive that it’s really hard to make affordable housing [projects] pencil out.”

Back in 2015, shortly after his election, Assessor Wilson and his staff went to work scrutinizing their database of all publicly owned properties throughout the county that could potentially be used for affordable-housing development. This scrub included not only county-owned land, but also properties owned by the City of Seattle, Sound Transit, and the University of Washington. They found roughly 300 parcels larger than 20,000 square feet and within a quarter-mile of transit hubs.

These properties, as Wilson put it, are what’s left over from major government construction projects. “It’s stuff that was bought for a large capital project usually, often for staging areas or things like that, and the agency gets done with it and then they go ‘Oh yeah, we may need that’ or ‘Yeah, we’ll get around to selling that,’ and they never get around to selling it,” he said.

But the troublesome state law requiring that agencies get compensated for the market-rate value of transferred land still got in the way of these initiatives. Wilson said the statute has led to many of those parcels staying “dormant.”

During the 2018 legislative session, state lawmakers passed House Bill 2382, which undid this rule and now allows local governments to sell surplus property at below-market value—or transfer it for free if it is used for affordable-housing purposes. That prompted Wilson to revisit the list of surplus properties his office had compiled years earlier. In March he asked Tim Overland, managing partner at Overland Real Estate and a member of the board of Bellwether Housing (an affordable-housing nonprofit), to look at roughly 180 of these publicly owned sites from the perspective of a real-estate developer to identify issues that would prohibit the near-term development of affordable housing. Overland narrowed the list to 26 government-owned empty sites that could be developed.

Additionally, he partnered with Blokable, a budding construction company based in Vancouver, Wash., that specializes in modular housing—a type of residential construction in which units are prefabricated in warehouses, then transported to and installed at the project site. They came up with cost estimates for housing projects at three of the sites best suited for development. On one site—a roughly 12,000-square-foot lot on Bellevue Avenue East in Seattle’s Capitol Hill neighborhood owned by Seattle City Light—Blokable and Overland estimated that building a 31-unit modular apartment complex would cost roughly $7 million in capital construction.

Compared to traditional “brick-and-mortar” affordable-housing developments, modular housing projects are significantly cheaper. According to Kelli Larsen, chief program officer for Plymouth Housing, the ballpark range for capital construction costs of non-modular affordable-housing projects is between $25 million and $30 million. For example, the construction costs of Anchor Flats—a new 71-unit Bellwether Housing project in South Lake Union that received City of Seattle funding in 2017—were estimated to be around $23 million, according to records provided by the Seattle Office of Housing.

Additionally, the construction timeline for modular housing is considerably faster than traditional projects, advocates say. “It’s going to be three or four times quicker than conventional construction, which would take one to two years in the construction phase alone,” Overland said. “Modular construction is really the only way that we are aware of that could fast-track the construction process.” By comparison, at a Blokable development in Edmonds, a single unit was installed and practically ready for a tenant in the same day.

King County is getting in on the modular housing game as well: County Executive Dow Constantine announced on Aug. 21 that the Department of Community and Human Services recently placed an order for 29 modular units to build several affordable housing projects throughout the region with ambitious completion timelines of roughly one year.

“It looks kind of attractive to find a way to do that in a factory and truck them in and place them on site,” said Dan Malone, executive director of the Downtown Emergency Services Center, a homeless housing and services provider. “At a minimum, it looks like it can be done a lot faster, and it might be able to be done less expensively.”

Wilson said the smaller size of the parcels that were identified as suitable for affordable housing development are better suited for modular housing development. “If you’re going to try and build traditional brick and mortar stuff [on these parcels], it probably doesn’t pencil out for you. You probably need a larger mass.”

Despite the appeal of modular housing, the public land that Overland and the Assessor’s Office identified still needs to get into the hands of those who can bring affordable-housing projects to fruition. And, according to Wilson, it’s been tough getting local agencies to move quickly on getting connected with nonprofit developers and service providers. “What we’re doing for the moment … is trying to match-make between agencies and nonprofits to say ‘Look, can the two of you talk? Is there a potential deal here?’” Wilson said.

Overland had identified eight publicly owned parcels as priority candidates for affordable-housing development. In addition to the Capitol Hill parcel owned by Seattle City Light, one is located adjacent to the construction site of the new King County youth detention center in Central Seattle and is owned by the county, while six are owned by Sound Transit and located near Link Light Rail stations in Southeast Seattle. But so far, only the county has tentatively committed to transferring its property for affordable-housing development.

Cameron Satterfield, a spokesperson for the King County Facilities Management Division, wrote in an email that once the new detention center is completed in 2020 (the parcel is currently being used as a parking and staging area for construction workers), the agency will start fishing for potential partners for affordable-housing development on the parcel. “Given the location, it’s likely the surplus property will be suitable for affordable housing. Then, the county could either enter into a partnership with a developer to build affordable housing, or offer the property in a [request for proposals] to a developer for affordable housing,” he wrote.

Similarly, Sound Transit spokesperson Kimberly Reason wrote in an email that while they’ve been contacted by the Assessor’s Office about the parcels, they haven’t received any specific plans or project proposals from him or his staff. “Sound Transit is interested in hearing more about the ideas in question and seeing if and how they fit into Sound Transit’s Equitable TOD program. We need to receive and review the concepts before we can comment further,” she wrote. Sound Transit recently codified the changes in state law into their own internal policies requiring that the agency first offer surplus property around light-rail stations to affordable-housing developers.

Seattle City Light spokesperson Scott Thomsen told Seattle Weekly that the agency needed the Bellevue Avenue lot for equipment that will help reroute power in case some other portion of the grid gets damaged. “We have plans for that property. That’s not one that we are looking to sell,” he said.

In Wilson’s mind, local agencies need to get serious about quickly mobilizing their surplus property for affordable-housing development. “With a couple of the public agencies we’ve talked to over the past year, we’ve gotten a kind of ‘Oh, that’s an interesting idea, but that wouldn’t work for us,’ and then you kind of say ‘Well, what about that property?’ ‘Oh, um, can I get back to you on that?’,” he said. “One of the challenges that we will have here as a region is, ultimately, do we have the will to solve this problem?”