Yesterday, City Councilmember Sally Bagshaw released a draft resolution that would halt Mayor Ed Murray’s plan to coax and then evict the dozens or hundreds of homeless Seattleites camped in the area known as the Jungle along I-5. The draft resolution was released at an afternoon meeting of Bagshaw’s Human Services and Public Health committee, following a morning filled with dueling press conferences on the seventh and second floors of City Hall. Also, the ACLU says it will sue Seattle if the city evicts.

Murray Draws First

At an 11 a.m. press conference, Mayor Ed Murray backtracked on his plan, announced last week, to clear the stretch of unauthorized homeless encampments along the I-5 known as the Jungle. (The mayor’s timing appears to have been a successful attempt to beat the council to the punch. Sally Bagshaw’s office confirms that Monday, Murray’s office asked her for 48 hours to consider her draft proposal; she assented.) Murray told reporters that while he still considers the conditions in the Jungle to be literally the worst place in Seattle for people to camp, he does not have a definite timeline for when the Jungle will be cleared, voluntarily or otherwise. “We’re making this up as we go,” he said. Previously, the city said campers would have about two weeks to leave one way or another, according to Crosscut’s David Kroman.

“We’re not going to do a sweep,” Murray told reporters, adding that it would take a while for the city to “empty” the Jungle. Asked if that meant that campers who didn’t accept shelter could remain in the Jungle, or if he just didn’t like the word “sweep,” Murray responded: “Let me be clear. We’re going to continue to offer people services and we’re going to continue to offer people services [sic]. If we believe people are in a place where they are in danger, if you want to call it a sweep, call it a sweep. I call it trying to save lives.”

Murray also objected to the public narrative surrounding his actions toward the Jungle. “I know people want this story, because it’s the old story in Seattle, ‘Mayor bulldozes homeless, throws them in bad situations’,” he said. “But we’re actually having a very different dialogue.”

Councilmembers Respond

Immediately following Murray’s press conference on executive’s seventh floor, councilmembers Sally Bagshaw and Mike O’Brien hosted a hastily-er arranged press conference on the legislature’s second floor to respond to Murray’s comments. “I really want to say thank you to the Mayor,” Bagshaw said, “because he has come a long way toward moving the process to what we want to accomplish.” O’Brien concurred, saying that the “intensive” outreach by Union Gospel Mission, a religious nonprofit that’s partnered with the city, is “a good thing.”

Then they got down to brass tacks. “Until we have housing for folks, simply saying ‘You can’t be here’ just relocates them,” O’Brien said. Bagshaw agreed, calling for more 24 hour shelters instead of the “11 hour shelters” that kick guests out each morning. She also criticized how the mayor’s office has used one statistic—a reported ninety one calls to 911 for the Jungle so far this year—without context. “Our fire chief this morning, in front of our public safety committee, said that his people had responded 300 times to just [two] addresses down on 3rd Avenue,” she said.

Bagshaw’s Committee

And then the power went out, in City Hall and throughout downtown. But it was up and pumping again by 2 p.m., in time for Bagshaw’s committee meeting, which began with a litany of objections to evicting Jungle campers. “What does it say about the alternatives we are offering to people if being in the Jungle is preferable to those alternatives?” said Kris Nyrop of the Public Defender Association. Alison Eisinger, executive director of the Seattle/King County Coalition on Homelessness, recalled Isaac Palmer, a homeless man who was sleeping under the cover of blackberry brambles in 2007 when a city-contracted tractor-lawnmower chopped into his head and killed him. This, Eisinger said, is what happens when homeless people are driven further underground than the Jungle. Representatives of Columbia Legal Services presented the council with an alternative resolution which would only allow the city to evict campers if they can offer those campers real housing, not just emergency shelter.

On the other side, a commenter who identified himself as a representative of the Neighborhood Safety Alliance (whose conservative approach toward the homeless I’ve written about previously) called for campers to be evicted quickly.

Perhaps the strongest rebuke (councilmembers later called it a “threat”) to the mayor’s plan came from Jennifer Shaw of the ACLU of Washington, who said that her organization is “in the process of preparing litigation” against the city if and when it proceeds with the evictions. Shaw said she couldn’t provide further details.

Part of the impetus for the meeting was Bagshaw’s draft resolution, which we first reported on Monday. Her working draft is designed to quell the executive’s fears about the living conditions in the Jungle while also preventing mass evictions, at least in the short term. Saying that only five to ten percent of current Jungle residents are likely to end up in the city’s already-inadequate shelter system, the resolution proposes a “person-centered outreach continues in [the Jungle] to move people to safe and permenant spaces and clean [the Jungle] without ‘sweeping’ people.” It also proposes, as Bagshaw has before, bring porta potties, garbage cans, and needle recepticles to the Jungle. During the meeting, Murray’s public safety advisor Scott Lindsay told the committee that he doesn’t think that’s feasible.

Throughout the meeting, Bagshaw, O’Brien, Bruce Harrell, Tim Burgess and Lisa Herbold questioned several mayoral staff and Jeff Lilley, Union Gospel Mission’s president. Lindsay reaffirmed the mayor’s morning statement that the Jungle outreach “is not a two week process…There is no hard timeline.” Instead, he said, the mayor’s office will rely on UGM to decide how long to do outreach. Lindsay, Lilley, and Burgess each noted how helpful the threat of impending eviction has been by “provid[ing] motivation” for campers to accept UGM’s offers of shelter, as Lilley put it. Deputy Mayor Hyeok Kim emphasized that Murray’s plan does not “criminalize homelessness” and police will not arrest people simply for being homeless. Asked by Herbold whether police might arrest campers for trespassing on state property, Kim was unsure.

What the Jungle’s Residents Are Saying

Asked on Tuesday what they’d do if and when the city forces them out, residents of the Jungle had different plans for where they will go. Three residents agreed to give us an overview of their circumstances, and how they plan to better them.

I encounter middle-aged Brian Davis while he’s raking litter from the ground around his campsite beneath the thumping concrete of I-5. He says he’s been in the Jungle for almost two years. He doesn’t go to shelters because “they’re not very clean. They’ve got the bedbugs.”

What will you do if evicted? “Wrap up and find another spot, I guess, unless they come at us with some kind of housing,” he says. “That would be great.” Davis cautions, though, that other campers may be more reluctant. “A lot of people want to stay here…They’ve been here for a long time, and it’s their home.”

Jerry Dean is starting up a small, contained fire outside his tent in the grassy area just outside the dark cave of the I-5’s underbelly. The youngish man says he’s been in the Jungle for about six months, after losing his children. “[I] didn’t want to face my family or deal with anybody I knew,” he says, “so I just went where I could hide out, you know?”

Validating a claim made by UGM president Jeff Lilley and the mayor’s office, Dean says the pending eviction has convinced him to apply for enrollment with the Light Under the Bridge ministry program, which serves food to the homeless. “It’s known to heal people up, get them back to where they need to be,” he says. Dean supports the plan to clear the Jungle. “It sounds right,” he says, but cautions that Seattle may not have the manpower required to keep the Jungle empty. “There’s like a thousand different ways to get in and out of this place,” he says.

Paige Comca, 33, says she came to the Jungle to care for a friend who has seizures. She’s on methadone, and became homeless two years ago after a break-up with the boyfriend she lived with. Comca says she isn’t sure whether she’ll accept emergency shelter, camp elsewhere, or join an RV. Or maybe take another option: trading intimacy for shelter. But Comca hopes not. “I could probably find somebody to stay with, but it would likely be…a guy that would want something for it,” she says.

Right now, Comca’s goal is stabilizing her life. “I’ve always eyed that little fruit stand job at Pike Place Market, ‘cause I’ve got bad jokes for days,” she says, laughing. “Or if I could get an instrument again, I could very well make a decent living just busking on the street.”

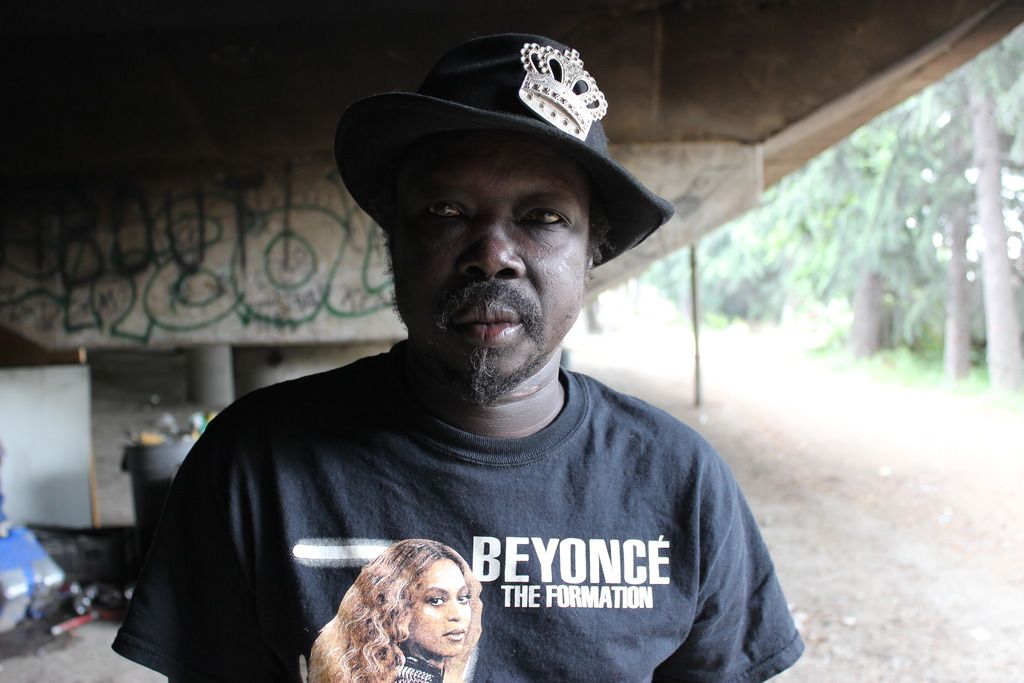

Asked where he will go if pushed out of the Jungle, Andrew Majak (pictured below) says that he’ll likely move under the West Seattle Bridge. Majak says he’s homeless because of immigration issues. His neighbor Charity says she’s uninterested in emergency shelter because she would “still…be homeless.”