A lot of things felt wrong to Leah Griffin when, in April 2014, she tried to get help following an alleged sexual assault. She arrived at Swedish Medical Center in Ballard in crisis—exhausted, disoriented, and bleeding—but was told that they “don’t do rape kits here.” If she wanted forensic evidence collected for a possible prosecution, she’d have to go to Harborview on First Hill. When she reported the attack to the police at the North Precinct, she waited for two hours in the lobby, crying, before any officers agreed to take her statement—in a private room only because she demanded it—and when she ultimately met with King County prosecutors, she felt she was blamed for the rape, and criminal charges were never filed.

A few months later, once she’d muscled through the worst of it and the shock had turned to rage, she channeled her frustration into hundreds of e-mails, phone calls, and complaints to anyone and everyone with the power to make decisions about any of it: state legislators, U.S. senators, every member of the Seattle City Council and the King County Council, the police chief, the state hospital association, the Joint Commission, local reporters. “There were so many problems with how my case was handled, there were so many issues I wanted to address,” she says now. She wanted to do “everything I could to figure out who it was that had the authority to do anything about any of these problems.”

Among them: Rep. Tina Orwall (D-Des Moines), who ultimately helped launch several bills in Washington state designed to address some of the problems Griffin faced—including one that established a task force on which Griffin now serves—and U.S. Sen. Patty Murray, whose staff in September 2014 listened to Griffin’s litany of complaints, from hospitals not providing sexual-assault forensic exams to police and prosecutors’ seemingly callous treatment of traumatized victims. “I just laid it all out there,” Griffin says. “And the thing that her team really picked up on was this lack of access to rape kits in hospitals.” Speaking now after several years of advocacy experience on all of these issues, Griffin believes that “this is a problem that nobody even knows exists. Everyone I talk to about it is shocked that it’s the case that you can go to an emergency room and they don’t have the resources to collect evidence.”

Murray, who spoke briefly with Seattle Weekly from Washington, D.C., says she was indeed shocked. After Griffin went to a hospital in Seattle, assuming she was doing what was needed for a criminal investigation (and for her health), “the first thing she was told was, ‘We can’t help you here. You have to go somewhere else,’ ” Murray says. “Just the thought of that happening to somebody who’s just been attacked is horrendous. I, like probably most people, found it incredible to believe that that’s what’s happening.”

Lucy Berliner, director of the Harborview Center for Sexual Assault and Traumatic Stress, says she remembers a visit from Murray around that time—early 2015. “She came by here when she was hearing about this whole situation. It was so interesting. It just never occurred to her that it wouldn’t be possible for everyone looking for a [rape] exam to get one.”

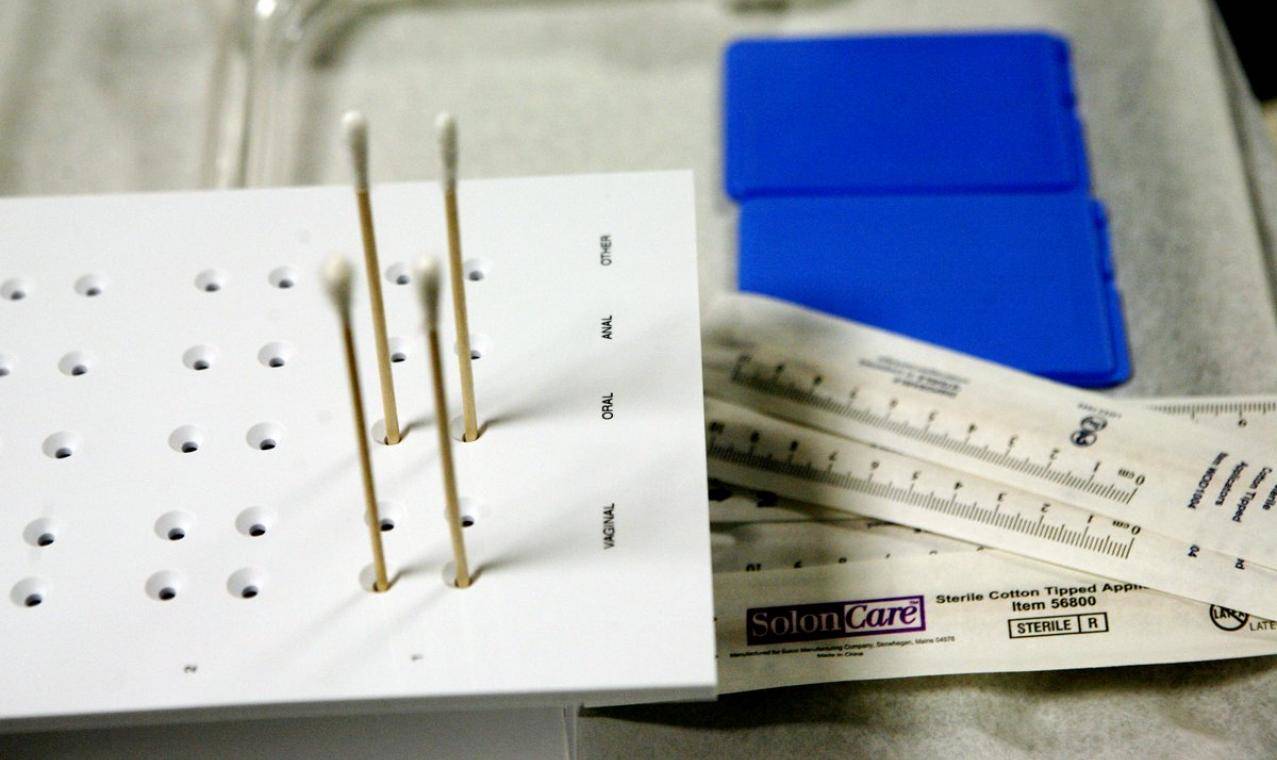

And so, spurred by Griffin’s experience, Murray started making moves. She wanted to know what the state of things was both in and outside of King County, so she asked the Washington State Hospital Association to survey its member hospitals. The report found that most Washington hospitals—79 percent—can technically provide forensic exams for survivors. However, in part due to the difficulty of maintaining a consistent pool of trained Sexual Assault Nurse Examiners (SANEs), nearly three-quarters of hospitals surveyed refer patients to other hospitals at least some of the time. That can mean the difference between having forensic evidence for prosecution and not having it, as sometimes that evidence is no longer available even a day later. “It’d be like your house getting burgled and the police show up and there are fingerprints everywhere, but they don’t have a fingerprint kit,” explains Griffin. “Everybody would say that’s absurd. But that’s what we’re doing right now for rape.” Some Washington hospitals have no protocol in place at all to help those patients.

“It’s costly—it’s definitely a costly endeavor to cover every hospital,” says Terri Stewart, coordinator of Harborview’s SANE program, which has expanded in recent years to include 25 trained nurses who are contracted to work at five different county hospitals, including Swedish First Hill, Valley Medical Center, and the UW Medical Center. The plan next is to get to Northwest Hospital, and eventually to Swedish’s Ballard location. But that takes time, money, and expertise. “SANE programs are hard because our nurses all have other jobs,” Stewart says. “There’s a lot of turnover. Right now we have two nurses on call, pretty much every shift. But we still aren’t at the point of having two nurses 24/7/365.” Still, she says, “I think King County is a lot better positioned than where we were.”

All in all, things look better for survivors in Washington these days—but less so across the nation. The vast majority of U.S. emergency rooms do not have access to SANEs, according to the International Association of Forensic Nurses; CEO Sally Laskey says only about 17 percent do. And when Murray, following her request for a Washington survey in 2015, requested a national report from the Government Accountability Office, that report found not only a lack of trained SANEs, but also a startling lack of data around the issue, period.

In May 2016, Murray introduced the Survivors’ Access to Supportive Care Act (SASCA). It would, among other things, provide the resources to conduct a detailed national survey of the kind done in Washington to determine where the gaps are. It would also implement federal standards of care (none exist right now), a grant program to expand access to SANE training, a national task force to address the quality of the exams, and a national best-practices clearinghouse so that health-care providers can improve the quality of care.

SASCA was referred to the U.S. Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions last year and went nowhere. This year, Murray is reintroducing it to Congress, with Griffin’s help. “She is the primary driving force,” Murray says. To pass bills at any level, lawmakers need stakeholders, and Griffin has been willing to tell her story, over and over and over—including in front of Congressional staffers in Washington, D.C.

“Leah is someone very unique, who’s got a heck of a lot of courage, and the willingness to make things better not just for herself, but really for everybody around her,” Murray says. “I have tremendous admiration for her.”

Griffin says advocacy can be a coping mechanism, too—“a way to turn something terrible into something really positive.” Earlier this year she became determined to fly to D.C. and agitate for the bill. She figured she’d just go, and try to set up meetings with lawmakers herself. But Murray got wind of her plans and gave her a huge boost: Once Griffin did head to the Capitol in late June, she was stacked with meetings. She attended four or five meetings a day for nine days straight—and everyone was into it. “I was really encouraged by how supportive the Republican staffers were,” she says. “Because this bill has a funding element, I assumed that if there was going to be opposition, this is where it would be. And I didn’t encounter that at all. … There was nobody that just said no. There was nobody that was critical. It was positive.” Despite all the divisiveness and polarization on every other issue, Griffin says, “It feels like if anything could pass this Congress, it is this.”

Although SASCA didn’t move last year, things are different this year: For one thing, in April, four members of Congress launched a Bipartisan Task Force to End Sexual Violence, a group that has already hosted roundtables on addressing the rape-kit backlog and on national access to SANEs. A Congressional staffer told BuzzFeed News that such a task force is “more important than ever under the current administration.”

Griffin, for one, is hopeful—and stubborn. And she’s still angry. “I think anger is a wonderful motivator. I don’t have as much rage as I used to have, but I still have anger. And I wanna fix this.”

sbernard@seattleweekly.com