Danni Askini slept on the floor of a Stockholm apartment during her first four weeks of exile from Seattle. Sweden’s summer sunlight cast an unwaning glow on boxes strewn about the spacious rooms, illuminating the emptiness of her temporary quarters. The vacationing owners had allowed her to stay at their place before they moved to another home; a gracious gesture that Askini, a transgender activist and the former executive director of Seattle’s Gender Justice League, had come to rely on as she attempted to get back on her feet in a new country.

Yet the isolation was deafening. Askini, 36, had deactivated her social media accounts and stopped using her cell phone out of fear that her location would be tracked or that she would face further harassment. Her limited Swedish proficiency and inability to open a bank account made basic purchases — and seeking legal and social services — a challenge. The only glimpses of the outside world came every other day when she would make phone calls to her mother, husband, and best friend in Seattle.

“I was trying to not spiral into despair,” Askini said as she reflected on her first few weeks in Sweden. But recurring thoughts of abandonment, frustration, and alienation kept her up at night. Accustomed to elevating the marginalized voices of others, the tables had turned on Askini. In Seattle, Askini had helped spearhead a lawsuit challenging the Trump administration’s transgender military ban, along with founding a nonprofit. She also ran for a state House seat in the 43rd Legislative District in 2016 before dropping out of the race to pivot her focus to fighting against I-1515, an initiative designed to limit access to bathrooms for transgender people. Now she was the one seeking help. “I feel erased,” she said, deflated.

Her escape from Seattle began in July, following the doxing of her family members, as well as death and sexual violence threats from white nationalist and neo-Nazi groups that escalated between May to late June, according to a United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights letter that detailed the allegations of her ordeal. The letter that redacted the names of the alleged groups stated that Askini had received over 12,000 hate emails over a two-week period. (Seattle Weekly has chosen not to describe the threats in detail so as not to jeopardize Askini’s asylum claim.)

Askini’s fear that her life was in danger grew along with the increasing harassment. She had strong ties to Sweden, having previously held a 10-year residence permit in the Nordic nation and having an ex-husband who still lived there. All that was required for Askini to take a sabbatical overseas for a few weeks was the renewal of her 2007 passport, which had expired in 2017.

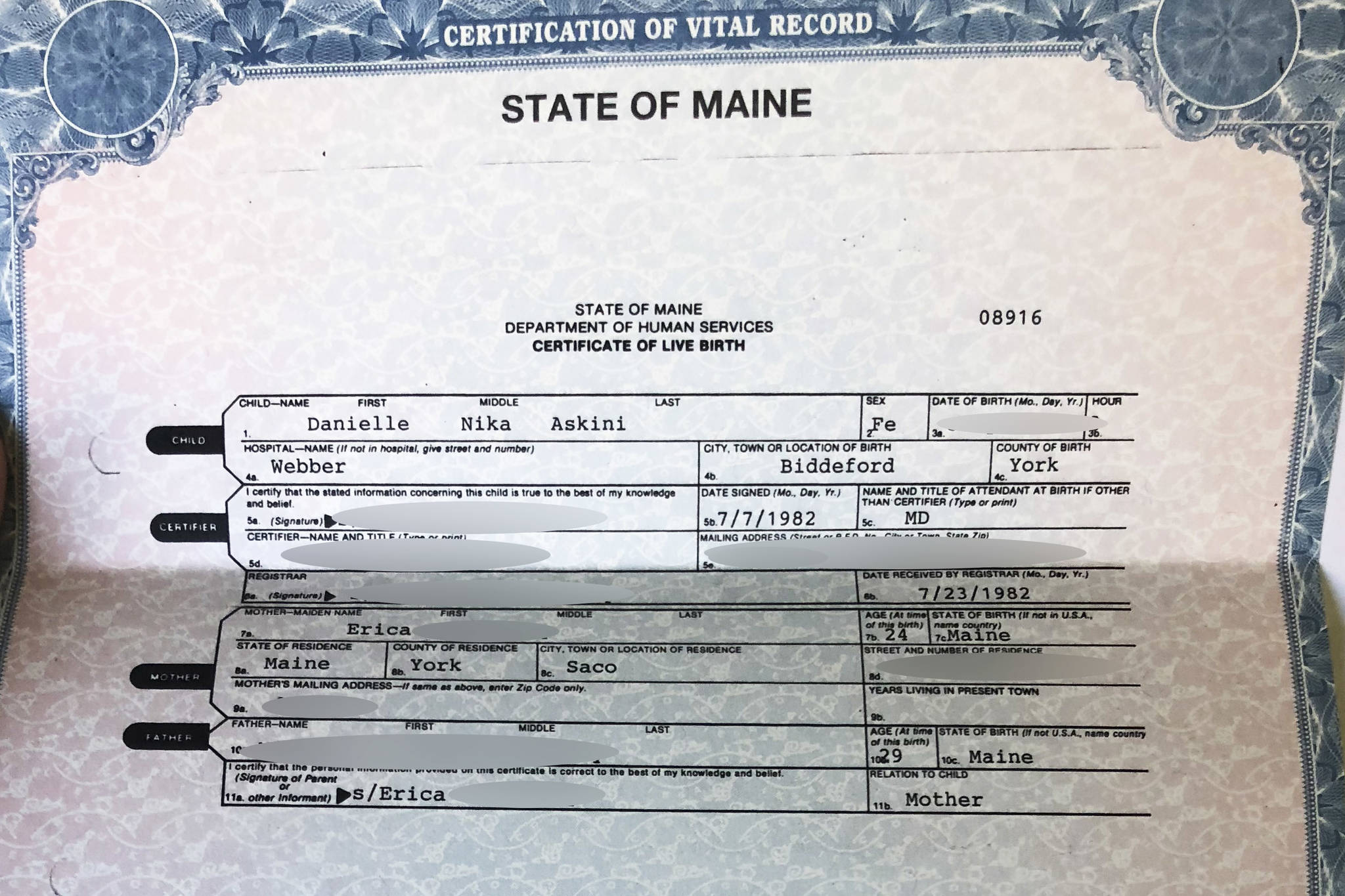

But when she attempted to apply for a new passport in late June, the U.S. Department of State Seattle’s passport office asked Askini for her previous names and proof of her U.S. citizenship, according to Askini and the letter. Although she had legally changed her name and gender marker nearly two decades previously and was born in Maine, Askini was allegedly told by a U.S. State Department official that her 2007 passport was fraudulently obtained and that she had not “established citizenship” because she’d failed to show proof of her completed gender reassignment and all previously used names. Her original birth certificate was ordered sealed in 1999, and the State of Maine Office of Vital Records had issued her a new birth certificate with her gender marker changed to “female,” as shown in a copy of the document sent to Seattle Weekly.

In a panic, Askini worked with two lawyers and the Maine Attorney General’s Office to unseal her birth certificate and child welfare records there — remnants of a life that she’d left behind long ago. Then with the help of U.S. Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-WA), Askini secured an emergency two-year passport that allowed her to travel to Sweden in July.

Now Askini says she is stuck in Sweden and fears that she will be imprisoned upon her return to Seattle, or worse: detained in a U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement detention center if the State Department does not accept her proof of U.S. citizenship. As a result, Askini is attempting to claim asylum in Sweden, although she believes that her chances are slim. The Swedish government denied her request for a lawyer and her appeal to be granted representation, according to a copy of a Swedish Migration Agency rejection letter that Seattle Weekly received from Askini. Her asylum claim hearing that was originally set for Nov. 19 will be rescheduled.

“I am a Trump refugee,” Askini said. “His presidency has caused the situation that put me here.”

At the crux of her tribulations lay what Askini believes is the U.S. State Department’s discrimination against her as a trans woman, a bias emboldened by the Trump administration’s rhetoric regarding marginalized communities. Recent actions by the administration to roll back transgender protections bolster her claims, she attests. Just last month, a New York Times article revealed a memo detailing that the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) plans to limit the definition of gender as either male or female, which would be determined by genitalia at birth. “The sex listed on a person’s birth certificate, as originally issued, shall constitute definitive proof of a person’s sex unless rebutted by reliable genetic evidence,” the memo stated, according to an Oct. 21 New York Times report. HHS will propose the new definition to the U.S. Department of Justice by the end of the year. If accepted by the department, the definition could be used by other government agencies.

The U.S. State Department wrote in an email to Seattle Weekly that the department was prohibited under the Privacy Act from responding to Askini’s specific allegations about the rejection of her passport, but noted that there has not been a recent policy change in adjudication of transgender applicants. A 2010 department policy change only required applicants to provide certification from a physician proving treatment for gender transition; previously, gender markers could only be amended with documentation that proved sex reassignment surgery.

“The passport adjudication policies that have been in place since 2010 remain unchanged. The Department of State is committed to treating all passport applicants with dignity and respect, including transgender individuals,” a Department of State official wrote.

In regards to the HHS memo, the official added that the Department of State could not “comment on another agency’s alleged communications.” When asked whether Askini could be detained in an ICE detention center upon her arrival in the U.S., the official again noted that it could not comment on her individual case, but that “in general, a passport issued for less than the full validity period (10 years for those 16 and older and 5 years for children under 16) may be used for international travel just like a fully-valid passport. This includes travel to and from the United States.”

U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), the federal agency that manages and controls entry into the country, could not address Askini’s specific case. However, a CBP spokesperson wrote Seattle Weekly in an email: “Determinations about admissibility are made by a CBP officer based on the facts and circumstances known to the officer at the time of the inspection. However, if the traveler is a U.S. citizen and presents a valid U.S. passport, issued to them, they will be admitted to the U.S.”

Yet Askini doesn’t want to take the chance of returning to the U.S. without a guarantee from the federal government that she will not be accused of having fraudulently obtained her 2007 passport, a felony offense that could lead to 10 years of incarceration. “I still don’t know — does the State Department think that I have committed a crime? Have they referred it to the U.S. Attorney’s Office?” Askini pondered, noting that the department also hadn’t addressed her concern.

Her fears are compounded by statistics on abuse in correctional facilities: a 2009 National Prison Rape Elimination Commission report revealed that incarcerated transgender people are at an increased risk of sexual abuse.

Moreover, Askini no longer has a passport in her possession. She attempted to apply for a new 10-year passport a month after arriving to Sweden in July, but the application was deemed incomplete on Sept. 26, according to email correspondence between officials at the U.S. Embassy in Sweden and Askini’s attorneys. Askini had submitted her temporary passport along with her mailed application that was to be returned to her in Sweden, but she said the passport never arrived. In the meantime, Askini’s 90-day visa was soon set to expire.

Email correspondence between Askini and officials at Sweden’s U.S. Embassy that were sent to Seattle Weekly detailed her escalating frustration and fear that she was not safe anywhere. Stuck in Sweden without a passport or a visa, Askini said that she had no choice but to apply for asylum. On Oct. 3, she sought asylum and was later granted an asylum seeker card that will allow her to stay in Sweden while she awaits her request for sanctuary to be processed, according to official documents from the Swedish Migration Agency. The agency will then determine whether she is eligible for a residence permit after conducting an investigation and a hearing in which she will explain her reasons for seeking asylum. Asylum investigation wait times have increased in recent years, owing to a record number of people who applied for asylum in the country in fall 2015. For that reason, Askini said she believes that the Swedish Migration Agency’s denial of her petition for counsel and speedy scheduling of a hearing forebodes an unfavorable outcome.

In total, she said that she’s talked to 16 lawyers to try to address the legal quagmire.

Amid it all, she’s kept a keen sense of humor; it’s how she has coped with stress since she was a teenager. Even if she’s not granted asylum in Sweden, she said she plans to continue appealing and then try her luck with other countries: “Like Oliver Twist, I’ll hold out my bowl and ask for more porridge from Canada, Australia, New Zealand,” she quipped.

She’s not the only transgender person to be denied a new passport in recent months. A July report by the LGBTQ-focused publication Them detailed the ordeals that Askini and another trans woman named Janus Rose faced in renewing their passports. The article stated that Rose had received a passport with a female gender marker last November; then she attempted to renew it after recently legally changing her name. However, a U.S. Department of State official allegedly told her that her passport couldn’t be renewed without a new doctor’s note, according to Rose’s July 25 tweet.

Aside from a few articles that addressed the phenomenon, Askini said that her claims have largely been ignored. A few days after the release of the Them article, NBC News reported that Askini and Rose’s situations were unique and not reflective of a trend or change in policy. The National Center for Transgender Equality also released a statement on Twitter in July that cited the recent instances of the passport office rejecting the renewal of transgender people’s passports as “unusual circumstances and bureaucratic mistakes.”

NCTE has investigated recent concerns about passport processing for transgender people. Our full statement below: pic.twitter.com/OTjogXdH5H

— National Center for Transgender Equality (@TransEquality) July 28, 2018

The reactions have left Askini feeling deflated. “I’ve shared my story countless times with millions of people to try to humanize trans people,” said Askini, adding that her high-profile presence came with a risk. “I painted a bullseye on my back five years ago when I started Gender Justice League and it took five years for that bullet to catch up with me. And now it’s here, and where the fuck are people?”

Askini’s downward spiral was sudden. In Seattle she ran a nonprofit, had a car and an apartment, and was recently married. Now she lugs around her possessions in trash bags and suitcases as she crashes on various acquaintances’ couches in Sweden. Her mental health has also taken a dive in the past few months, she said, the trauma of harassment and sexual abuse driving her to forego sleep to walk around Stockholm at night.

As a result of preparing for her asylum hearing and trying to live day-to-day without her support system, Askini has had to step down from her leadership at Gender Justice League. She’s unable to complete the projects that she’s been working on for years, such as the Coalition for Transgender Prisoners and the Coalition for Rights and Safety for People in the Sex Trade, while living abroad. Instead, she focuses on administrative tasks, writing grants, coaching, and managing the other employees at Gender Justice League to run the organization without her.

Along with dealing with the trauma of the recent alleged harassment, Askini has also had to relive the physical and sexual abuse that she experienced as a minor when she unsealed child welfare documents in Maine to try to renew her passport. “To have that … drudged up from the past as if who I was when I was 15 is somehow more authentic, and more valid than who I am as a 36-year-old woman,” she said.

Askini’s sudden departure from Seattle without a return date in sight has left a gaping hole in the trans community that she’s advocated on behalf of for a decade, say her friends and family. Sophia Lee, the board chair at Gender Justice League, noted that others in the organization had to assume additional roles to shoulder Askini’s workload. “We had to change a lot of the dynamics within the organization to try to make ends meet,” Lee said. In the wake of Askini’s absence, the nonprofit created a new organizational structure that will be unveiled Dec. 6 at the Gender Justice Award fundraiser. The loss of Gender Justice League’s founder has personally affected Lee, who has had to take on additional office hours and speaking engagements, write more blog posts, and encourage the board to be more active in the organization.

It’s also caused a general sense of paranoia to ripple throughout the local LGBTQ community as people wonder if something similar could happen to them. “A lot of the issues that occurred affected Danni specifically, but it has been felt throughout the community,” Lee said. “We have a lot of people reaching out, worried and asking what happened with Danni’s situation to draw parallels to themselves to see if they’re also in danger.”

The separation has also deeply affected Max Aubain, Askini’s husband, whom she married a few days before fleeing for Sweden. Over the past few months, Aubain said he’s had to put off “everything” from his career, to friendships, to starting a family with Askini. Their communication has been relegated to video chats and emailing, and sometimes he learns news about her life through Facebook. “It’s been extremely difficult,” Aubain said. “I don’t think I’ve ever faced something this difficult in my life.”

If Askini is granted asylum, then Aubain would try to move to Sweden too. In the meantime, they try to maintain a sense of normalcy by sharing the funny things that happened to each other throughout the day, the future trips they’ll take together, and the apartment that they’ll share when the events of the past few months are over. “We have been trying to look toward the positive future as best we can,” Aubain said. For now, his advocacy has concentrated on providing Askini and the rest of her family with emotional support. He’s had to transition from working full time to part time as a patent agent for a law firm so he can send Askini her belongings and help her with other logistics.

Although Askini feels that she has largely been erased, some organizations, politicians, and supporters have increasingly voiced their concern about her safety. A Gofundme legal fund that began in August had raised $20,403 of its $20,000 goal by Nov. 21. Last month, the Seattle LGBTQ Commission tweeted that the group was “highly concerned about the well being” of Askini.

“Danni has made a huge impact on the trans community here and in the U.S. in general,” Seattle LGBTQ Commission Co-Chair Jessi Murray told Seattle Weekly. “She’s done so much for our community that I really hope we can do something to stand up for her rights as well.”

URGENT: The @SeattleLGBTQ Commission remains highly concerned about the wellbeing of #Seattle resident and prominent trans activist and human rights defender, Danni Askini, who had to flee the U.S. due to threats against her safety. pic.twitter.com/bnJstkqpNo

— Seattle LGBTQ Commission (@SeattleLGBTQ) November 17, 2018

The commissioners encouraged Seattle City Councilmember Lisa Herbold to draft a recently passed resolution that affirms the city’s commitment to the United Nations Declaration on Human Rights Defenders in response to the targeting of local activists including Askini. The Transgender Law Center also released a statement that detailed the organization’s concern about Askini’s treatment by the U.S. State Department.

Yet the proclamations haven’t brought Askini any closer to returning. Askini’s mother, Erica King, said that her absence has especially taken a toll on the family this month: “Thanksgiving is her favorite holiday, and she won’t be here to make holiday dinner for us. I go to bed every night and I pray for her to be safe. That’s the most important thing to me,” King told Seattle Weekly as she broke into tears. Her main point of contention is that there would be any disbelief surrounding the validity of Askini’s Maine birth certificate. “If they can do this to her, then they can do this to any American citizen,” King warned.

mhellmann@seattleweekly.com