A handful of activists staged a “Slow Internet Walk” from the Comcast’s downtown office to City Hall to protest slow internet speeds in Seattle, and to call for municipal broadband—city-run internet—as the solution.

It wasn’t your average march, at least in terms of speed. “It took us over an hour to walk what should have been 20 minutes,” said Devin Glaser, Policy and Political Director of Upgrade Seattle, a campaign for equitable public internet, who joined the group of activists on the slow, rainy trek to City Hall. “But I think we’re all used to that experience when you’re expecting something to come quickly and then it downloads slow, it stops, it stalls, it fails on you.”

The mission of Upgrade Seattle and activists is to press the city to build a municipal broadband network that would be run as a public utility — sort of like what Seattle City Light already does, but for broadband. Like many major cities, Seattle’s internet is operated by large for-profit corporations like Comcast, CenturyLink, and Wave. Those calling for municipal broadband to Seattle see it as an equity issue.

“This is something that actually is critical for families,” said Laura Bernstein, an activist with the Seattle “Yes in My Backyard” urbanist movement who joined the walk on City Hall. “I used to be a teacher—I think that kids that have access to the internet at home, it’s another way to be set up for success, and if you don’t have that internet access you’re not on a level playing field.”

In the lobby of City Hall, the activists met with city councilmembers Kshama Sawant and Rob Johnson, who jointly proposed an amendment to the city budget that would allocate $300,000 to municipal broadband last Monday. The money would pay for a 10-year implementation plan. Glaser presented the two councilmembers with handmade awards made out of CDs.

“Municipal broadband is something we all agree on, working people, small businesses,” Sawant said. Sawant was met with a loud cheer when she finished her remarks with “Let’s keep fighting.”

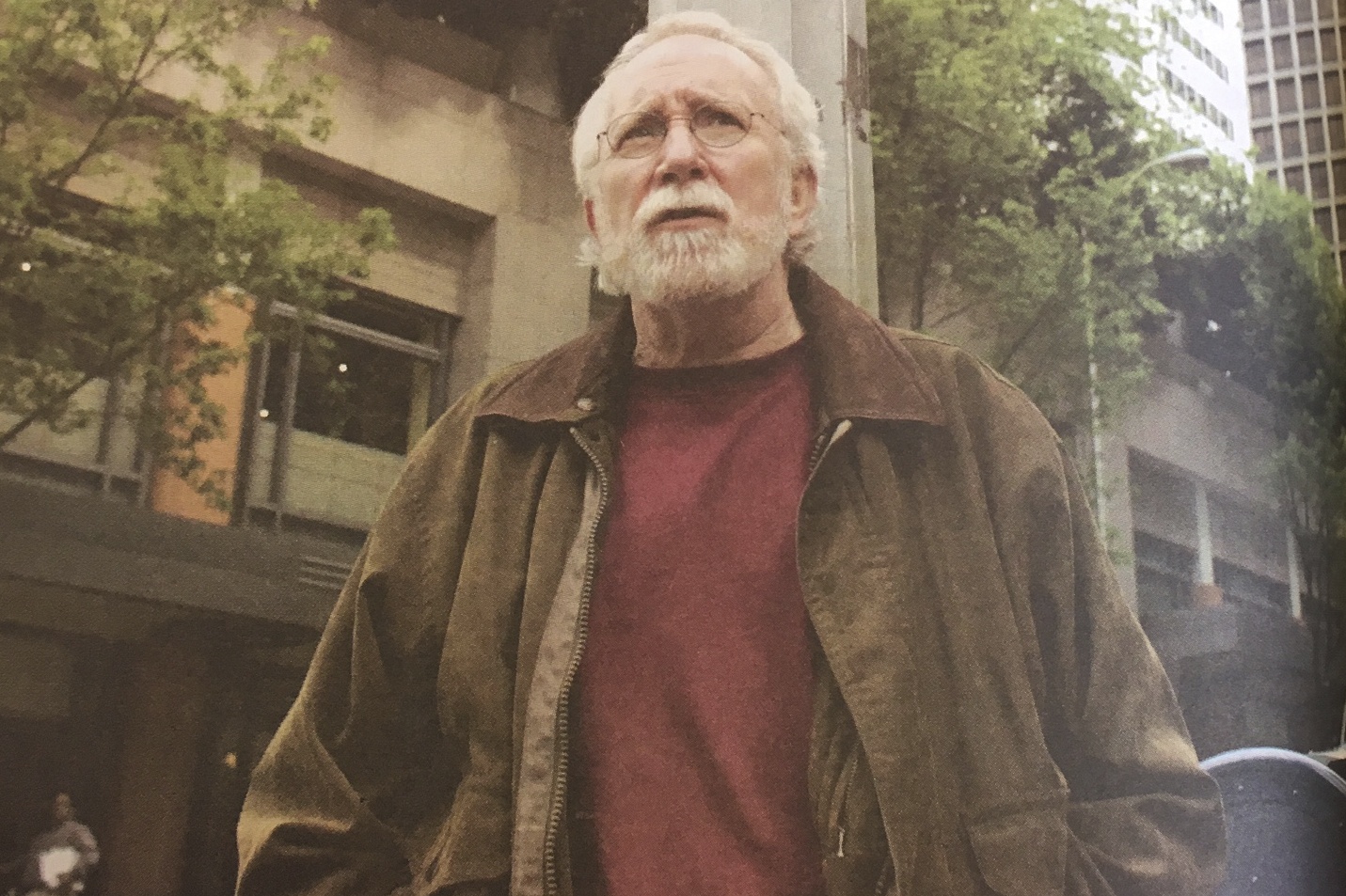

Glaser from Upgrade Seattle wore a crown made of cables on his head, with the two ends sticking like devil horns. Around his neck he carried a router.

“It’s actually been a really great two-week period for municipal broadband,” he said. Glaser cited not only Sawant and Johnson’s amendment, but also the fact that, on October 17, the City Council unanimously approved the City’s 2035 Comprehensive Plan for the next 20 years, which included a dedication to broadband.

“It’s a commitment, it’s putting it into our DNA as a city,” Glaser said.

Sawant and Johnson’s amendment will still need to be approved by Tim Burgess for the budget. If it isn’t approved, Glaser said Upgrade Seattle and the activists will put pressure on City Council members to vote on it separately, with the hope that at least five will. And if it’s passed, he believes, it will be a step forward toward figuring out the ins and outs of how municipal broadband will actually work.

“Say next year there’s a new federal grant from a new presidency who’s putting money into cities again, we would actually say, ‘Hey we could take that money and we have a product for it…We actually know day one, week one who’s got a job, who’s hiring, where we’re building.”

A city study conducted in 2015 concluded that building municipal broadband would cost between $480 and $665 million, which was deemed too expensive to build while staying within budget. However, Glaser points to another finding from the study — that a majority of Seattleites would support it.

“So people already want this and they should be reminded that it’s an option, because the political will is there and the imagination’s there, it’s just connecting those dots for people.”

If Seattle does build a municipal broadband network, it would be the largest city to achieve this. Only small towns like Chattanooga, Tennessee and Cedar Falls, Illinois, have succeeded.

“We would set a precedent,” Glaser said. “It fits Seattle’s reputation as an innovative city.”