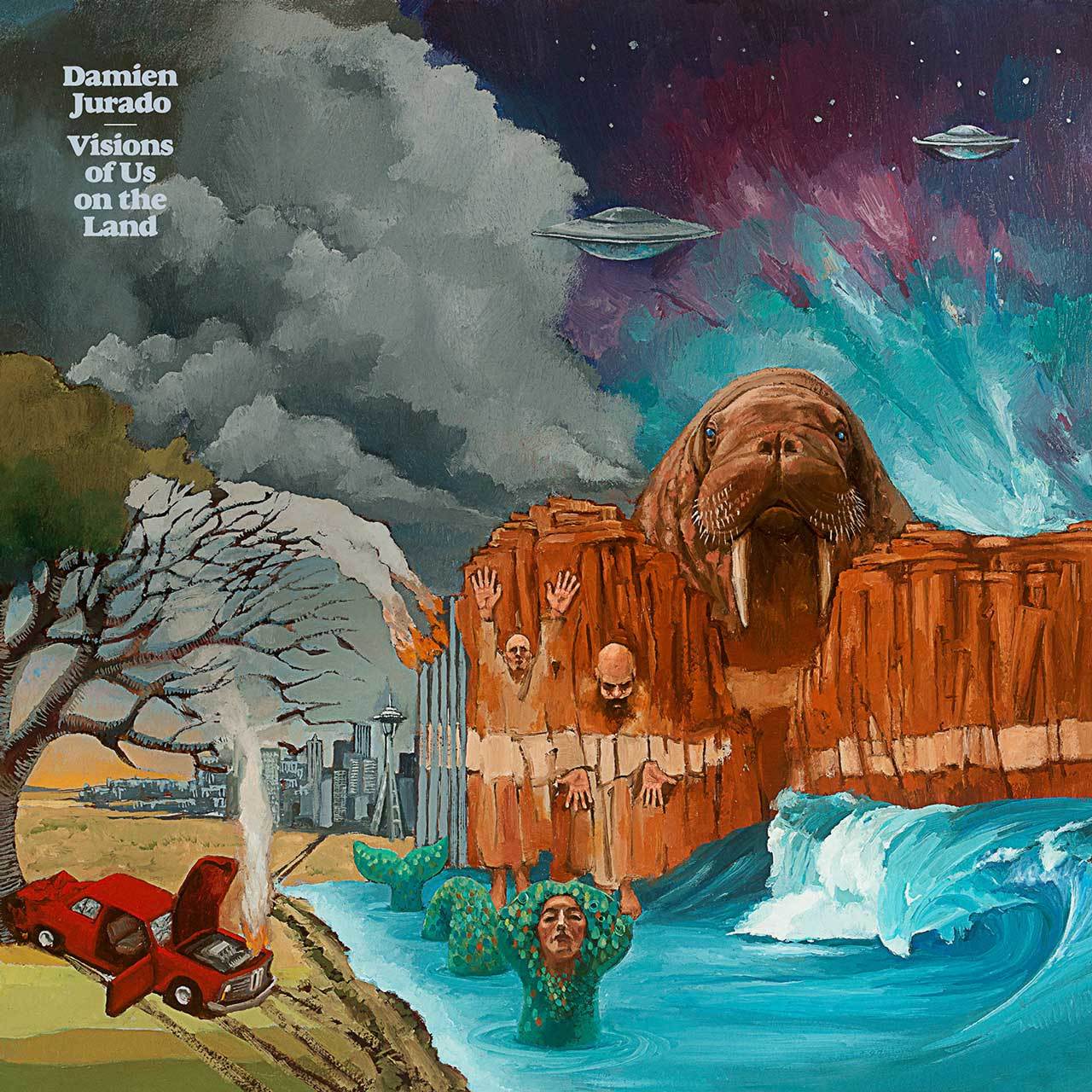

When he released Visions of Us on the Land last week, Damien Jurado completed a journey. It was one that started four years ago when the Seattle songwriter released his 10th studio album, Maraqopa, the first of what would end up being a three-album cycle, The Maraqopa Trilogy. Jurado says that at the time he didn’t know he was at the outset of a massive artistic undertaking, but it is clear from the wild, squalling electric guitar that snakes through that album’s first track, “Nothing Is the News,” that he was setting out for new terrain.

Jurado did possess something of a map to this new land, a dream that inspired that first album and the one that came after, Brothers and Sisters of the Eternal Son. The latter album, a baroque work of psychedelic pop released in 2014, pitched the oft-understated balladeer into a shimmering, fantastical world. It was a striking work, not just for the new sounds that Jurado was bringing in, but for the story. The titular brothers and sisters here are a doomsday cult that Jurado’s hero discovers in Maraqopa, the small town that serves as a place of refuge after he crashes his car in the first album. The entire album is spent in the grips of this cult as it searches for “resurrection signs.” It is a world and an album steeped in Christian theology—a theology that proved to be something other than fictional for Jurado, who during the release concert for the album at Seattle’s Neptune Theatre declared his faith in no uncertain terms by leading the room in a “worship song.” He had joked earlier in the night that he was a cult leader. Everyone laughed, but the reality was clear: This was more than just a dream.

And that is a big deal. Jurado had emerged from Seattle’s alt-Christian scene of the ’90s, but his faith was only occasionally mentioned in song. By 2008’s Caught in the Trees, it was completely absent. For the secular listener, a born-again stance from a singer whose appeal is found in his soul-bearing songs could well be a deal-breaker. So the stakes are high for this latest album, which begins with Jurado’s hero still in the grip of the cult.

Musically, Visions of Us on the Land picks up where Brothers and Sisters left off. This is the fourth album that Jurado has recorded with producer Richard Swift, a partnership that has transformed the artist. Since working with Swift, Jurado has introduced bright synthesizers, deep grooves, strange sounds, and the occasional lacerating guitar part, as well as production that casts the singer’s plaintive vocal as an eerie echo. In the hands of Swift, Jurado’s songs, previously lonely landscapes, have become densely populated, sometimes with people, other times with ghosts. Swift’s influence has also brought out Jurado’s fine-tuned sense of rhythm, an underappreciated aspect of Jurado’s earlier work that allowed him to play long solo-acoustic sets without coming off as redundant. Early on Visions, it is the percussion and that sense of rhythm that sets the mood. And it is a tense one, as the two openers describe, in broken lines, an ugly scene. Set to an anxious beat and swelling strings, “November 20” recounts a death, or a drunk, a show gone off the rails. On “Mellow Blue Polka Dot,” a strumming, rattling, haunted thing, the situation becomes clearer. “Stick around,” Jurado sings. “It gets worse, in your shoes, here’s your curse.”

All is not great in paradise, it seems, and over the course of the first 10 songs of this 17-track, 52-minute work, Jurado tells a tale of disenchantment. It’s an uneasy, sometimes ominous series of songs that never really open up to let the light in. Even when they settle into a groove, as on “QACHINA” and “ONALASKA,” the mood is overcast. And when overstuffed with buzzing guitars, slapping hand drums, and Jurado’s cawing backing vocal on “TAQOMA,” the sound becomes disorienting in its darkness. But Jurado, uncommonly comfortable in this space of disillusionment, turns in two of the most beautiful, tender ballads of his career. “Do we still go on, long after rewind,” he sings in the contemplative, doubting “Prisms.” “Who’s to really know, once the exit’s closed.” The 10th song appears to act on that doubt. It is a lament sung over lightly picked guitar, a piano tracing Jurado’s vocal. “Tried my hand as a brother, failed as a man and a friend,” he sings. And later, “Lord take the weight, I won’t need it.”

And so, on this album, Jurado is trading the role of true believer for defector. It is, in this way, a mirror image of Maraqopa, an album in which Jurado suffers another disillusionment. But it is a kind of faith in music that is lost in Maraqopa. Throughout the album Jurado is squabbling with fans and journalists who want something from him that he cannot give. He doubts the power of music to provide any real meaning, deeming it all “ghosts of words in a song.” At the moment of his spiritual awakening, on the track “This Time Next Year,” he explains that “To find you wear a golden crown/To be in light, transcending sound/To be lifted from the ground.” He has transcended sound, he says, and as proof he goes the entirety of the next album, Brothers and Sisters, and the first 10 tracks of Visions without mentioning his craft.

That changes with track 11, “Walrus,” a fantasia of twinkling bells, wandering horn, and lively organ set to a clippity-clop beat and a funky bass line. “I’ve gotta go back to the city,” sings Jurado, his tone slightly sinister but free at last. “Walrus” feels, compared to the previous 10 tracks, like a different world. “Found my place, near the back of the pen,” Jurado sings. “Dig myself from the hiss of the tape again.”

The rest of the album is pure light, musically and lyrically, with Jurado singing sweetly from a different kind of place filled with love, memory, and song. The God for whom his hero sacrificed music in the beginning is not mentioned here, but you can sense a presence. On the final track of Maraqopa, the hero surrenders his musical agency by exclaiming that “We are songs to be sung.” Here, on the glorious, cinematic single “Exit 353,” he amends that thought, or maybe evolves it. “Are we all not lost in song,” he sings, “feeding back until we’re found?”