In a review of Matt Dillon’s Pioneer Square restaurant two years ago, I wrote that “ultimately I like The London Plane. Only maybe once a month. And maybe only on, say, a Wednesday, and a sunny one at that.” The restaurant—which is also a larder, bakery, and flower and novelty shop—has gone on to win awards and national acclaim, and its palate-cleansing, Mediterranean take on a tight curation of vegetable-forward dishes continues to be a lovely lunchtime sanctuary.

Now he’s opened a wine bar in Capitol Hill’s Chophouse Row building called Upper Bar Ferdinand (1424 11th Ave.) and is again serving a limited menu that, this time, looks more to the East—specifically to Japan. His skill at creating open, airy spaces punctuated by precious, unusual displays of food and flora is evident here as well. The high wooden rafters and a remaining band of concrete wall, strung with lights, echo the whole architectural concept behind Chophouse Row—a mini-replica within the greater whole—and are both arresting and soothing. Within the deconstructed space, a log burns in an open fireplace, cured meats hang behind glass, and bay leaves overflow from large vases and trickle down walls, as do bunches of dried garlic and chili peppers. Large jars ceremoniously suspend things like aquatic-looking cauliflower mushrooms in the ancient practice of fermentation. The only “real” decoration is a blue-and-white-dotted Japanese-style cloth curtain that hangs from the upper balcony, along with midcentury modern wood chairs with light blue leather seats and wooden tables with one sky-blue stripe. There’s an undercurrent of purposefulness to the subtlety, and even the serene, seemingly taciturn staff are in fact incredibly eager to elucidate the unconventional menu.

Much of the food, like at The London Plane, is served cold or room-temperature—but here the focus of the changing menu is more on seafood. Six of the 10 plates when we visited derived from the sea, and they arrived on Japanese-inspired pottery, dishes that recalled those I have eaten from during 10-course Kaiseki meals in Kyoto: small plates that when grouped in an artful pageantry made sense, but that here, on their own, can feel a bit too singular. The line-caught halibut, cured on kelp with wild plum and thyme, is served in eight slices, each topped with a drop of the plum sauce and a tiny, lilac-colored thyme flower and served on a bed of kelp. While the fish is certainly fresh and the kiss of thyme evident, it’s nearly impossible to extract the flavor of the plum. The dish is served with a bowl of broth made from onion, soothing sips of salinity that you crave all the more for the intended, but ultimately unsuccessful, understatement of the halibut.

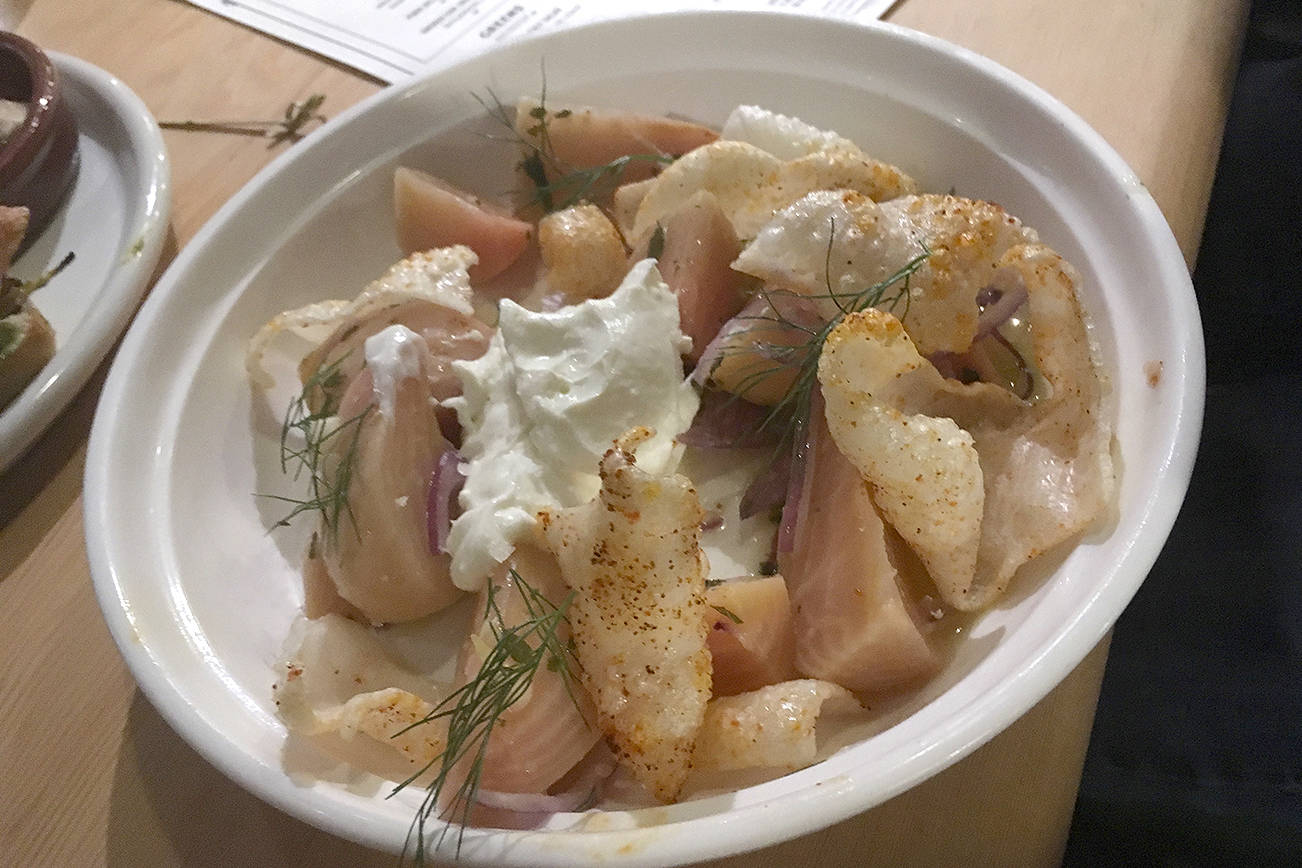

The raw, thicker slices of King salmon in a chilled whey “soup”—the whey, similar to buttermilk, brings acidity—is much better, the meaty grilled morels a woodsy match for the rich, marbled in-season salmon, both enlivened by leeks and wisps of dill. The steamed Vashon oyster custard is the most obvious nod to the Kaiseki meal and its chawanmushi course, a delicate egg custard typically seasoned with a fish stock, mushrooms, and bites of seafood studding the creamy base. In this preparation it’s appropriately silken in texture and well-attended by oysters. A side of fermented beach vegetables—various seaweeds and kelp—is a good, crunchy foil. At this point in the meal, however, we desired something heartier, and that bears underscoring. This menu is not meant to be treated as a meal (lest you leave hungry and with an underwhelmed palate), but as quiet gifts from the sea or earth to accompany a glass of wine or sake.

The oven-roast chicken with peppers preserved in cider honey and vinegar sounded like just the thing, though, to shake up our taste buds, and indeed it’s a half chicken cut into pieces and served beside one big, beautiful, pliant red pepper, all floating in an astringent, superbly seasoned broth. Yet the chicken, while moist and yielding, does not fully capture its essence. Despite rigorous dipping into the liquid, it remains on the bland side. Interestingly, the potato, yogurt, and salmon egg dip is aggressively briny and salty—served with grilled sourdough—and would have been a welcome addition to the table if our palates hadn’t already been subdued. And this is where Dillon loses me: In his reverence for the beautiful ingredients he sources, he often fails to allow the vinegars and broths and preserves he’s painstakingly crafted to coax forth the natural richness of the proteins. His restraint is but one step shy of perfection, and the tongue is left wanting.

Whereas at The London Plane the various housemade spreads and oils accentuate the rustic vegetables and meats, here the resulting labors of love seem overly tamed, particularly given the effort that goes into their creation. I believe in his process, and the commitment to quality; I just yearn for a little more exuberance on the plate.

nsprinkle@seattleweekly.com