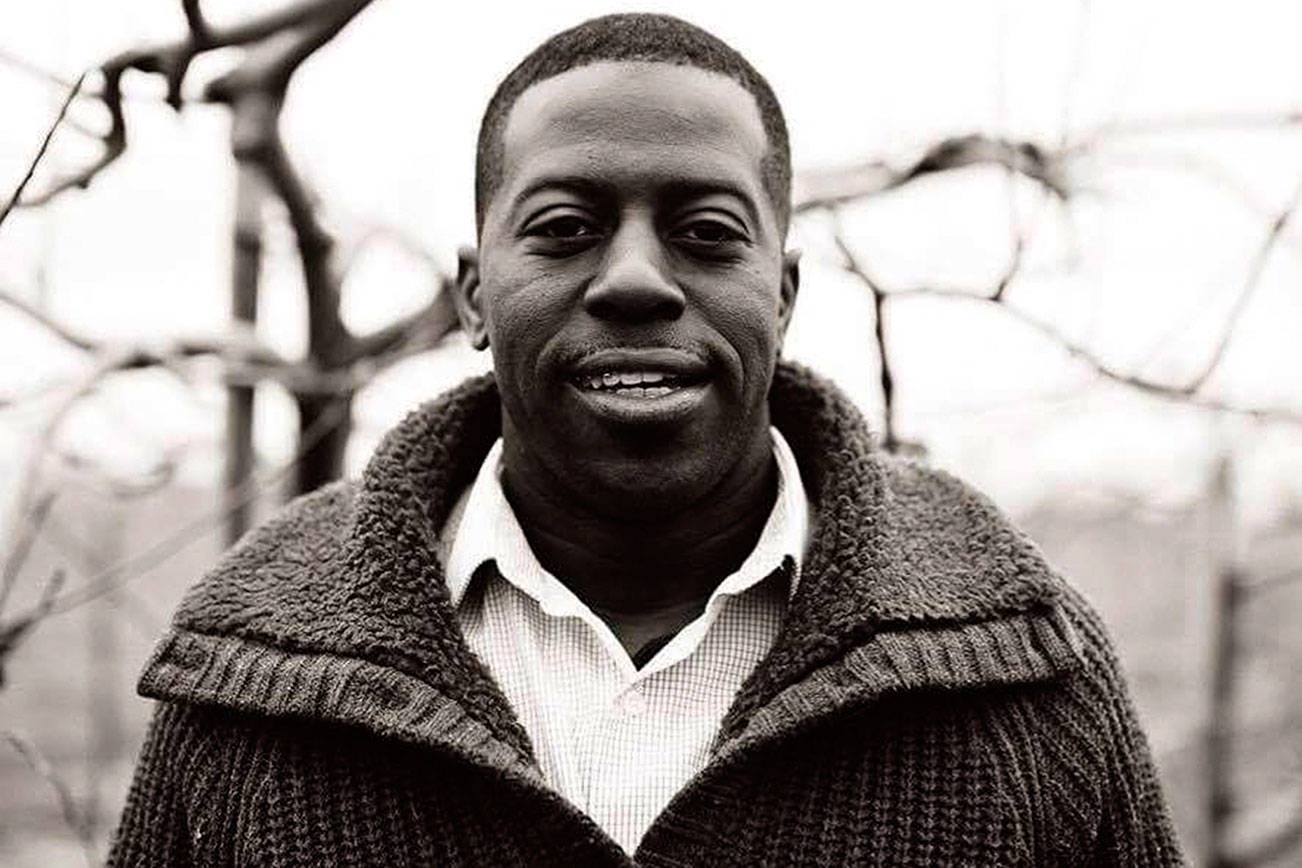

Larry Rock says that when he started in the brewery business, some customers would balk if he, an African-American man, jumped behind the bar to serve. “They thought I was up to no good,” he says. “Honestly, early on, people wouldn’t believe I was doing what I was doing, as far as customers. But once people got to know you, they see you’re passionate and you know what you’re doing.”

Rock was hired almost 30 years ago to be the original brewer at Pike Brewing, and has since spent portions of his long career with Hale’s and Maritime. His son also works in the beer industry, for Reuben’s Brewing in Ballard. They aren’t the only brewers of color in the region, but while Rock says the racial diversity in the Pacific Northwest brewing world has improved over the years, the change has been incremental.

At any given time there are 200 to 250 breweries in Washington and, obviously, many more in Oregon. But off the top of his head, Rock could name only a handful of brewers of color in the region. In Seattle there are only a few, including Manny Chao at the beloved Georgetown Brewery and Dan Lee at Odin Brewing. Rock, perhaps generously, cites nepotism as the cause.

“Believe me,” says Rock, “I’m thrilled to have this conversation because it’s something I’ve been talking about for years now. A lot of it comes down to who people’s friends are and who they know.”

He adds, “I’m not saying it’s a racist industry, but it’s an industry of familiarity. It’s really disappointing to me… . When you look at the overall beverage industry, there are very few minorities, even on the distributor side. You don’t see the outreach; people are comfortable dealing with who they know, and the majority of people in the beer business are white people.”

Lee, who was born in Korea but moved to Canada when he was 5, sees the lack of diversity as a result of language and cultural differences between Americans and immigrants. “When I think about what my parents went through and what they faced,” he says, “there’s always going to be racism—but to me the more fundamental reason is that a lot of immigrants didn’t have the language skills and cultural connections in a new culture.”

Lee, who got into the brewing world after taking a job with Miller Brewing in Milwaukee, notes that the world of brewing and sales requires specific skills to deal with a wide customer base. “Most of the people who came from [countries outside the U.S.],” he says, “these countries don’t have a rich tradition of brewing in the homeland—it wasn’t like people coming from Germany in the mid-1800s.”

While Lee says he hasn’t experienced any direct forms of racism, he has been mistaken for Manny Chao “on more than one occasion,” he says, laughing. He believes, though, the next generations of brewers will bolster the diversity in the field. But between now and then, he doesn’t want to see any “agency or some government official or some well-meaning person to artificially boost racial diversity—I want it to be organic.”

In addition to his call for increased face-to-face conversations in the industry, Rock says he would like to see more hands-on approaches to increasing diversity in the marketplace. At the top of his list is widening the appeal of the city’s beer festivals—those events where microbreweries show off their new wares to hundreds of thirsty ticket-buying attendees, often with live music and food trucks on hand.

“We need to make the festivals more diverse,” he says. “If I see any more folk bands or country rock there, I’m going to scream!” He laughs, though it sounds like a sigh. “We have to get Latin music, salsa bands, funk bands to draw in an audience. But, again, people are dealing with who and what they’re familiar with.”