Noel Lopez wasn’t typical of the street kids who hang around Westlake Park. He wasn’t a runaway or a throwaway. He had a caring family who were eager to help him. He wasn’t an aimless high-school dropout with few options. He’d attended a couple of years of college on a full scholarship, and later held a job as a parking valet and had his own apartment downtown.

He also wasn’t a kid. He was 25 in April 2008, the last time anybody saw him alive.

But Lopez was mentally ill. Diagnosed back in his hometown of Odessa, Texas, as bipolar, he began to spiral downhill after moving to Seattle five years ago.

That’s how he landed in the world of street kids—a world, it turned out, he was utterly unprepared for. Lopez didn’t understand the rules, or the consequences of breaking them.

On the morning of April 14, 2008, construction workers found his battered body at a job site on Seventh and Madison, just a few blocks from Freeway Park. Pools of blood were everywhere. Close by were the instruments that had been used to break his bones from head to toe and cause a hemorrhage in his brain: two-by-fours, an iron crowbar, and other heavy construction tools.

Lopez’s hair, cut into a Mohawk, had been spray-painted bright orange. The same paint had been used to scrawl several messages in one corner of the site: “I am God;” also, the word “Smurf” and the number 13, in Roman numerals.

The scrawls proved to be brazen clues that led straight to the murderers—and to guilty pleas just a few weeks ago. They were also cryptic signs of a subculture that roams downtown, with its own language, hierarchy, and—at times—brutal thirst for violence.

Manic and delusional, Lopez in his last months became so ill that he donned a Batman suit underneath his clothing. His family couldn’t get him committed to an institution because he was not deemed to be an imminent threat to himself or others. Instead he wound up being a victim himself, killed in a manner that the investigating homicide detective—a veteran of a hundred murder scenes—described as “extraordinarily violent.”

Lopez was born on Christmas Day in Odessa, Texas. He was Patricia and Gerald Lopez’s seventh son, a birth placement that according to folklore guarantees special powers. Young Noel did not take those auspicious signs lightly. “He thought he was magical,” Patricia recalls. And she tended to agree. “Everything came to him so easily,” she says.

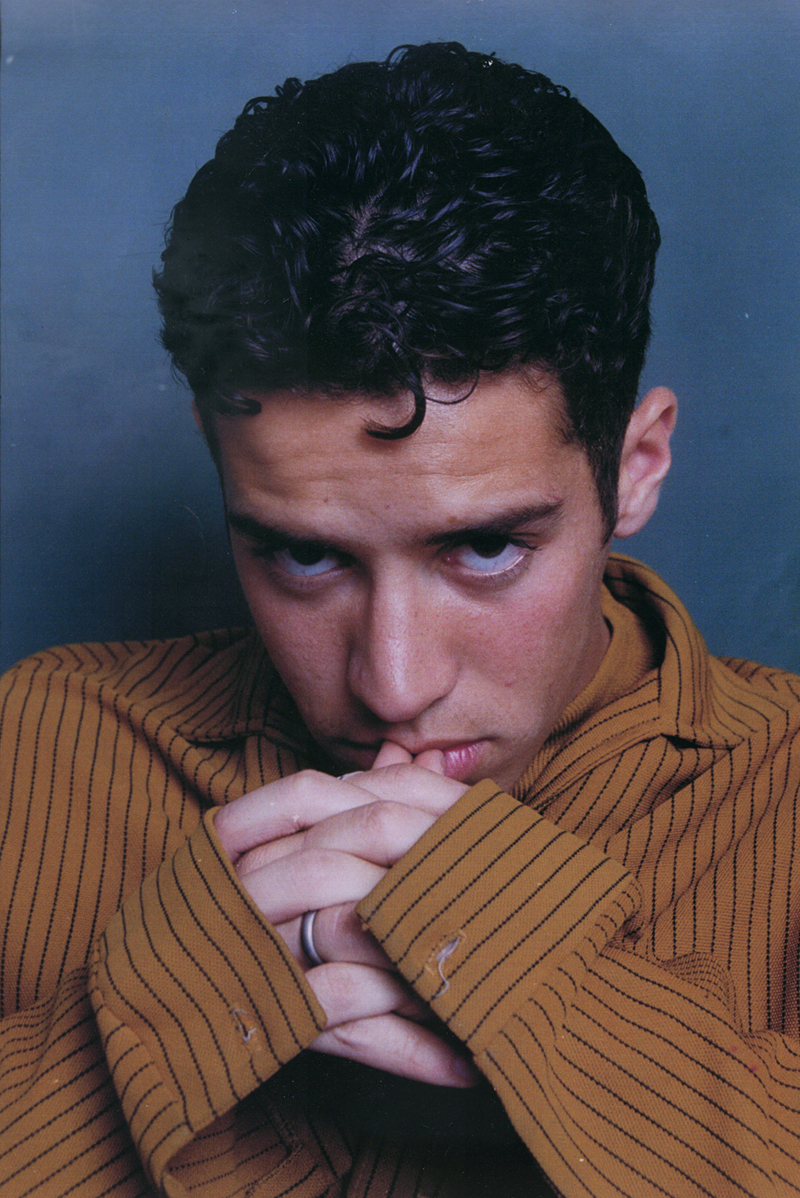

He did well in school, played soccer and the double bass, acted in plays at Odessa’s community theater, and won first place in a high-school artwork competition. He had dark-haired good looks and what his childhood friend, Dallas Kielhorn, called “a certain charisma.” “Everyone seemed to want to know him and be around him,” says his younger sister Amanda.

And he in turn wanted to be friends with everyone, whether they were white, black or Hispanic. According to his older sister Lita, that was pretty unusual in Odessa, a small west-Texas town known for its oil-and-gas-drilling industry, and as a onetime hometown of the Bush family. Lopez, like his siblings, crossed racial lines simply by being born. His father Gerald, a lawyer, is Hispanic. Patricia, a stay-at-home mom, is white.

Until Lopez went to Florida State University on a scholarship for Hispanic students, his family saw no signs of illness. But returning home after his freshman year, Patricia says, he seemed oddly irritable and impatient. “I didn’t take it seriously. I thought it was typical of college students.” By the following summer, however, it was clear something was wrong. He fought not only with his parents but with his siblings, to whom he had always been close.

“There was an aggressiveness I had never seen before,” Lita says, adding that he seemed “so moody and dark.” And he seemed to take the notion that he was magical much more seriously than before. “He thought he was a shaman,” his mom says. The family got him to a psychiatrist, who diagnosed Lopez as bipolar and prescribed medication.

Lopez decided not to return to college, instead accepting an invitation to stay with Kielhorn, who was by then living in Seattle and working as a house painter. Seattle was an artistic place and would be a welcome change from Odessa, Kielhorn told his friend. Kielhorn and his girlfriend drove all the way to Texas to pick Lopez up.

Once in Seattle, Lopez worked for Greenpeace as a successful canvasser, and “wholeheartedly believed that he was saving the planet,” Kielhorn recalls. But after a number of months, Kielhorn says, a roommate of Lopez called with bad news: “Noel was going off the deep end.” He had developed an obsession with Fight Club, the 1999 movie about a white-collar working stiff suffering from insomnia who seeks relief through fisticuffs. “Noel was trying to organize people to be a kind of underground force,” Kielhorn says.

Lopez was not so far gone that he couldn’t appear lucid. He wanted to be an animator and got himself admitted to the Seattle Art Institute. But then, according to Kielhorn, the symptoms got worse. Lopez would get a financial-aid check, and it would trigger a manic spending spree. “After the money was gone, he’d get depressed,” says Kielhorn.

More worrying was the company Lopez began to keep. He had moved into a first-floor apartment in Belltown, not far from the Institute, and had a habit of leaving his windows open and talking to passersby. Eventually he started inviting folks inside. “It got to the point where he was meeting some rugged people,” Kielhorn remembers.

“There’s something you should know about my family,” Lita says. “My parents were always taking in other people’s children.” They were usually kids whose parents couldn’t control them. Gerald and Patricia, devout Catholics who had produced nine well-behaved children and had originally wanted even more, were viewed as people who could straighten these youths out. Sometimes the newcomers would stay a week, sometimes a couple of years. The Lopez children jokingly referred to their house as the “Lopez Home for Wayward Youth.”

Lita speculates that that was why her brother started extending invitations. “He wanted to help.”

Lopez wanted to help one person above all others. “He told me there was this beautiful girl that was on the streets,” Kielhorn says. Lopez, then in his mid-20s, discussed with Kielhorn the possibility of adopting this girl, who was only 15. We’ll call her Eva.

But his interest wasn’t strictly paternal. “I know he had a romantic interest in her,” Kielhorn says. Indeed, court documents say he also talked about marrying her.

Meantime, Lopez started hanging out with his new friends in the places they congregated. One was Westlake Park, whose plaza offers several places to sit, socialize, and “spange” (which rhymes with “change” and means to ask for spare change). The other was Freeway Park, whose notoriously secluded walkways and alcoves offered a refuge from the downtown crowds—and a place, according to prosecutors’ theory of the case, for gangs of street kids to establish a name for themselves.

“I went to Noel’s place.” So says a woman who is known as Mama Voo and has, by her account, lived among street kids since she was 11. Although 29 now and living in a Capitol Hill apartment, she’s still a fixture of the scene—a large woman with nose and lip rings and, on a recent fall day, a purple bandanna wrapped around her head. She’d just approached a group of young people standing in front of the Starbucks on the plaza outside Westlake Center.

The kids yell “Nazi, Nazi!” and “6 up!” every few minutes—code for police and security officers on the horizon, prompting them to jump up from the building’s ledge, where they have been told not to sit. Meanwhile, Mama Voo explains what she knows about Lopez. She says Noel had been part of the downtown scene for six months to a year before his death. She and others would go to his place to play video games, “smoke a little bit of green, or just chill.” He would also let two or three people at a time sleep over, she says.

He struck her as “a kind-hearted” soul but “shy”—the “type of person you’d want to protect.” She says he didn’t talk much to the guys, who intimidated him. He was civil enough, “until he got some alcohol in him. At that time, he got kind of handsy.” Mostly he kept to the young girls.

She remembers one girl who “frequented his house on multiple occasions and took whatever he had to offer: pizza, a hot shower, a couch to sleep on.”

But she says that at some point, the two had a falling-out. One day at Westlake Park, she says she saw the girl sidle up to Lopez while he was sitting near the fountain. “Can I come over tonight?” the girl asked. “She looked all cracked out, like she’d been high for days.”

“No, I’ve got other plans,” said Lopez. “I’m going to a rave with some other kids.” She protested. He got mad. Then he stood up and started shouting: “Leave me alone. I don’t want to be around you.”

A couple of days later, according to Mama Voo, the girl started telling people “a bullshit story” about how Lopez had been molesting her.

“This was her way of getting back at him,” Mama Voo suggests. Also, she says, people on the streets throw around accusations all the time. “They like the drama,” she says. “You went to high school, right? That’s what it’s like out here.”

The crowd that hangs out in front of the Westlake Starbucks consists mostly of Juggalos, or at least of people who describe themselves as “down with the clown.” Juggalos are the cultish followers of Insane Clown Posse, a Detroit rap duo who dress up as freakish clowns and sing about killing people in gruesome ways. The Juggalos out here insist their affiliation is based on “family,” “loyalty” and “protecting each other”—but not violence.

They have little tolerance for the street kids who congregate just across Pine Street on “the stage,” a terraced platform beneath arch-like pillars. “That’s where the ravers hang out,” says “Rezen,” a 23-year-old with a dog.

“These kids are always high,” says Rezen’s boyfriend “Tank,” a 25-year-old wearing a cap with the ICP logo—a running man holding a hatchet. “They have to learn moderation.”

The Juggalos recognize that a number of ravers also consider themselves down with the clown. And they don’t like it. “It’s disrespectful to be a raver in a Juggalo family,” says a young man who calls himself L.A., adding that he better not see a person wearing the hatchet-man logo and “candy” (the brightly colored necklaces and bracelets that are ubiquitous in the rave scene). “We’ll tell them to take it off. If they don’t, we’ll rip it off.”

A 14-year-old raver who goes by “Zipper” relates how a friend of hers had his hatchet-man T-shirt ripped off, and another had her glasses taken off her face. Zipper and her friends keep their distance.

Lopez, true to his high school form, managed to cross social boundaries. “He was an everyone guy,” says Mama Voo.

Unfortunately, he also seemed to run afoul of the one cardinal rule that prevails in both sets: Older guys are not supposed to come on to young girls.

“That’s being a ‘chimo,'” says Flippz, a self-declared street mom, using the shorthand term for child molester. “That’s disgusting.” Say you’re a 20-year-old who comes on to a 13-year-old girl, says Flippz. “You get a warning.” After that, “yes, you’re going to get your ass beat.”

Tank, who has little respect for the young girls in the rave scene who “run around in their bras and panties,” has even less for the “creepers” who take advantage of them. “You touch little kids and you’re dead,” he says.

That’s one line Lopez may have sought to cross. Eva began telling her friends that Lopez had been coming on to her, and told one of her street “brothers” that she was scared of him.

One friend she complained to was 20-year-old Marcus Dennis. His street name: Smurf.

Interviewed later by police, Dennis offered a bleak autobiography. He said he had been “abused and tortured” by his mom’s boyfriends. He said he’d come to Seattle from Iowa to visit his mom because she was ill, but that “she didn’t have enough room with her boyfriend, so they dropped me off downtown.”

And so he began hanging out with street kids. Sometimes he slept under the Alaskan Way Viaduct, taking meals at the Union Gospel Mission and showers at the Chief Seattle Club. (Dennis told police he was part Native American.)

His shaved head might have made him seem tough, but he had a skinny frame and, according to Mama Voo, a prissy way about him. “Everyone picked on him,” she says. People called him a “fag” and “bitch.”

But Eva accepted him as her street brother. And complained to him about Lopez. “He keeps following her and, like, harassing her and trying to touch her,” Dennis later told the cops. He said other girls were complaining about Lopez’s advances as well.

The complaints made their way to another street brother, Steven Bauder, who went by the name of 13, or “XIII,” as it would later appear in bright orange paint. Six feet tall and bulky, with long straggly hair, he was a very different character from Dennis and fit into the street scene effortlessly. He called himself a Juggalo, and wore an ICP-style hatchet-man tattoo. He also sported a bracelet stamped with the initials CHID, which he said stood for “chaos, hate, independence, destruction.”

After high school in Portland, where he joined the wrestling team, Bauder spent about three years in the Army. The legacy of that experience can be seen in the way he spelled his last name to the cops in an interview, using a military phonetic alphabet: “Bravo Alpha Uniform Delta Echo Romeo.”

While he was in the Army in Texas, his mom died. She was only 40 and had had heart problems, according to Bauder’s stepmom, Jerrie Coppernoll. Maybe that’s what changed him. Something did, by his own account. In the Army, he told police, “I had everything I wanted and I lost it all and I fell apart.”

Bauder ended up in Seattle at age 21, apparently uninterested in an apartment or a job. “I’m a free spirit,” he told police. “That’s why I likes being homeless . . . If you have a job, you’re restricted to where you can go.” He said he slept at a particular squat under Freeway Park.

He seemed to like the respect he found on the streets. “I intimidate people,” he told the cops. That’s why he says he came to be known as an “enforcer.”

In the winter of 2007, Lopez, accompanied by Kielhorn, went home to Odessa for his brother Danny’s wedding, which was to take place on New Year’s Eve. “Noel got really excited,” Kielhorn remembers. “His manic side started building to a point I had never seen.”

Back home, Kielhorn says, “Noel started doing things that were really inappropriate.”

Lopez did not like then–President Bush very much. And it so happens that Odessa lays a special claim to the Bush family. It was the first place George H.W. Bush landed in Texas when he left the East Coast to seek his fortune in the oil business. With only one child at the time (George W.), Bush moved his small family into a two-bedroom, 800-square-foot rambler. The house still stands, next door to the Presidential Museum in Odessa.

Around 3 a.m. on December 27, someone set fire to the home. Firefighters quickly put out the blaze, but not before it had destroyed much of the living room and left a trail of soot and smoke. The house closed for a year for repairs. Odessa Fire Marshal Detra White says no suspect was ever identified.

Lopez told Kielhorn that he had done the deed: He had taken a tire and some phone books, set them aflame, and threw them in.

Kielhorn says Lopez never told his family. Even so, his parents and siblings were alarmed by his behavior during this stay. “He was able to control himself for the wedding, but by the time it was over, he was gone,” Patricia says.

“He’d loop from high energy to depressed to angry to ‘I’ve got some grand idea to rule the world,'” Lita says.

His parents had him committed to a state hospital. “I thought ‘Wow, Noel is going to be gone for a while,'” says Kielhorn. But Lopez could apparently still appear lucid when he chose to. Within days, Kielhorn says, Lopez had managed to convince the hospital to let him out, and he was back in Seattle in early January 2008.

He apparently wasn’t lucid enough, however, to keep up appearances at school and at work. The Art Institute asked him to leave (school spokesperson Mark Livingston declines to say why). He lost his valet job at the waterfront Marriott. And he was evicted from his Belltown apartment in March for failing to pay rent.

Lopez began sleeping on the streets, every once in a while spending a night or two at Kielhorn’s house. One day he showed up crying and badly scuffed up. He said the Juggalos were after him because of this girl he had been spending time with. “Those guys are going to kill me,” he told Kielhorn.

He apparently decided that if you can’t beat ’em, join ’em. On his last day in Kielhorn’s house, Lopez came out of the bathroom in the clown makeup that Juggalos sometimes wear. He had painted his face white and drawn dark circles around his eyes. His lips were painted into a frown. “I’m trying to fit in,” Lopez said.

A string of MySpace messages exchanged at this time among Bauder, then in Portland, and some girls, suggests that Lopez’s efforts were unsuccessful. The girls sought to incite Bauder to action, claiming Lopez was bothering them and trying to take over Freeway Park.

“You need to bead dude’s ass,” wrote a girl named Jinxy.

“I plan on it kiddo, no one fuks with my friends, I eard one of em tried to pick you up,” Bauder wrote back.

Jinxy: “Yeah and . . . he tried to be like this is my park and I was like mother fucker this aint your shit.”

Bauder: “Yeah, that’s MY park, and apparently he wants to fight me for the claim, which is a bad idea . . . ” As Bauder put it in an e-mail to another girl, “I am the king of freeway park . . . I’ll defend it any way I have to.”

On April 4, he returned to Seattle to do just that, he later told police: “It’s something that had to be handled.”

Meanwhile, the Lopez family made a last-ditch rescue effort. Kielhorn had called Lopez’s parents to let them know the danger their son was in. They dispatched an older son named Delano, then living in Wisconsin, to Seattle. Delano says he went looking for Lopez in Freeway Park but instead met two men—whom he would later identify at the trial as Bauder and Dennis—who said they intended to kick Lopez’s ass. Delano pleaded with them not to, saying, “He needs to be at a hospital.”

When Delano eventually found his brother, he was in bad shape. Lopez had lost his glasses and was delusional. “He said the lizard people that lived under the city would take care of him,'” Delano recalls.

Delano brought his brother to Kielhorn’s house and got a couple of counselors from King County Crisis and Commitment Services to come evaluate him. “They said that unless he was a danger to himself and others, they couldn’t commit him,” Delano recalls. So Delano booked himself and his brother into the Kings Inn, a hotel along Fifth Avenue downtown, and tried to talk him into returning to Odessa.

Speaking with Seattle Weekly from Ohio, where he now lives, Delano was reluctant to describe what happened in that hotel room. But clearly things did not go well. Two days later, Lopez walked out.

On April 13, Bauder, Dennis, Lopez, and a host of other street kids met at Freeway Park. At first the anticipated showdown was nothing more than a wrestling match. Dennis told police that Lopez had challenged him to compete “for the lordship of Freeway Park” as they were downing forties. “I just thought it would be fun,” Dennis said, adding that they were “trying to do that kung fu drunken fighting.” He said the match ended in a draw, whereupon Lopez challenged Bauder to the same.

Bauder described his fight with Lopez as a “no hitting, no kicking” wrestling match just “to see who wins.” Bauder said he did.

Later Lopez went to get more beer with Dennis and Bauder at a nearby grocery. Around 1:30 a.m. they ended up at a construction site (where the 7th & Madison midrise office tower was being built).

At that point, the fights became much more serious—and one-sided. In interviews with police, Dennis described breaking two-by-fours over Lopez and watching him crawl on the ground, crying and bleeding. When Lopez tried to get up several times, Dennis threw heavy construction equipment at him.

Meanwhile, Bauder told police, he punched and kicked Lopez, who was on the ground screaming “Stop!” Bauder also admitted to stomping on Lopez’s chest several times.

According to Bauder, the beating continued, on and off, for four hours. During breaks, he said, “we talked about him fucking up.”

Yet Bauder and Dennis both said during questioning that they didn’t expect Lopez to die. “He’s supposed to be alive so he can atone for his sins,” Bauder told cops, adding that dying was a “coward’s way out.” Both also insisted that when they finally left—after spray-painting Lopez’s hair (that was Dennis), tagging their street names, and declaring supernatural powers (Bauder said that might have been him, although he was too “shitfaced” to remember)—Lopez was alive. Each suggested the other might have returned to polish their victim off.

Not that they seemed concerned one way or the other. “I dunno if he survived or not . . . frankly I could care less,” Bauder wrote to Jinxy hours after the beating. To someone named Daimey he wrote: “The most satisfying thing in the world is whip kicking someone in the face and watching them fall over like a retard . . . Unless you left them in a pool of their own blood (and not some little puddle, I mean a fucking POOL), you didn’t REALLY kick their ass.”

Bauder’s correspondents seemed enthralled. “I heard you kicked the living SHIT out of Noel,” Jinxy wrote. “I love you so fucking much right now. I hope you threw a little extra in it for me.” “If I were with you right now, I would give you the BIGGEST FUCKING HUG I think you will ever receive in your life,” wrote another girl, named Heather.

Ultimately, all the victory laps run by the perpetrators did them in. The morning after the beating, both men showed up at New Horizons Ministries in Belltown, which has long catered to street kids. In the mornings, breakfast is served in a big common room, and afterward kids can use laundry machines, clean up, or crash on couches.

That morning, Dennis was carrying a pair of white sneakers coated in blood—”like a candy apple,” according to Tracy Cobbin, another kid who was there. Bauder’s right hand appeared to have a broken bone around a knuckle. “His face broke my hand,” Bauder kept saying, describing the beating he had just administered. Dennis chimed in too. As Eva, the girl whose complaints might have instigated it all, looked on, the two men laughed, bragged, and talked about hearing bones breaking as they hit Lopez with metal pipes.

Police learned all this from Cobbin. A couple of days after that memorable breakfast, Cobbin showed up at police headquarters unannounced and told all he knew.

Two and a half years later, Cobbin told the story again, this time from the witness stand. It was day three of the trial in King County Superior Court.

Dennis and Bauder had both admitted to beating Lopez pretty severely, but each claimed the other must have leveled the final blows. Judge Catherine Shaffer denied their request to be tried separately. Pointing fingers was going to be much harder with the two defendants sitting alongside each other.

So the main issue at the trial became whether Dennis and Bauder had intended to kill Lopez, since intent is necessary to prove first-degree murder. To argue their point, prosecutors had the MySpace exchanges as well as statements from Delano and Kielhorn about threats expressed to them.

And then there was Cobbin. Visibly nervous, the skinny 26-year-old appeared in court on Sept. 30 wearing baggy sweats and a white stocking cap. Just before he took the stand, a somewhat ragged-looking man in a sweatshirt and jeans—a friend of Bauder’s—whispered menacingly: “Sell out!” Police escorted the man out.

Cobbin began by giving a picture of his life on the streets in 2008. He worked as a ride operator at the Seattle Center Fun Forest three or four days a week, a job that apparently couldn’t cover his room and board. He sometimes stayed at a University District shelter called ROOTS, but it was often full. So he would go back downtown and walk around all night, feeling it wasn’t safe to close his eyes, until it was time for breakfast at New Horizons. He then described what he’d heard said that one morning.

Asked by prosecutors why he had come forward, he said: “I put myself in the victim’s family’s shoes. I felt I was just as much a part of it if I didn’t say anything.” (Cobbin’s attorney declined to make him available for an interview, saying he was out of the street life now, with an apartment and a young family, and feared retribution from the world he once lived in.)

All this seemed to be enough for the defendants and their attorneys. During a weeklong recess that followed Cobbin’s testimony, Dennis pled guilty. Shortly after the trial resumed, Bauder pled as well. (They took an “Alford plea,” meaning they don’t admit guilt but concede that there is enough evidence to convict them.)

Prosecutors had intended to argue that the crime was “gang-related,” which would have allowed them to seek a sentence of 30 years to life. Instead, they are seeking 25 years. Sentencing is set for Jan. 7.

On the street, a number of people seem to be siding with the more popular Bauder. “Smurf was the one that disfigured [Lopez] and left him in the rubble,” contends Mama Voo, voicing a commonly held theory. “He thought this was his chance to prove that he was somebody.”

Meantime, few have much sympathy for Lopez. Many street kids, particularly those, like Tank, who never met him, hold to the rumor that he was a chimo. Says Tank: “I honestly think he got what he deserved.”