The Central District is now home to the best French restaurant in Seattle. With the opening of L’Oursin(1315 E Jefferson St., 485-7173), JJ Proville, who has French and U.S. citizenship (and honed his culinary chops at Il Corvo and Art of the Table in Seattle as well as at New York City’s Gramercy Tavern), and Zac Overman, also a New York transplant and former bartender at Rob Roy, have created what looks like a classic brasserie. But the menu here extends far beyond the typical steak-and-moules frites, taking essential cues from the waters of the Pacific Northwest to inform French-focused cuisine.

What’s more, they’ve dedicated their wine list (and some of the beer list) entirely to organic vintages, many of which end up in some unusual but deeply satisfying cocktails. The Pourquoi-pas, for instance, takes as its base a concentrated sherry-like wine from Roussillon and combines it with spicy digestifs like benedictine. It has an inherent funkiness that grew on me (I ordered a second round). Meanwhile, a kir Normand swaps out the Champagne in the classic kir royale for an extra-dry cider from Normandy, preserving the bubbles but giving the sweet cassis an intriguing, yeasty bite. It’s rare that I begin a review discussing the beverage menu, but this one truly earns an early call-out.

That said, the tightly curated, boldly conceptualized menu is equally remarkable. There’s an emphasis on fruits de mer, but you’ll find more exotic items than just raw oysters; think instead of a whole sea urchin on the half shell served with toast, a dish that might scare a small child with round, black, spiky creatures engulfing the plate. Though I didn’t try it, I couldn’t help staring at our neighboring diners’ order. It’s truly a spectacle to behold, the creamy uni spread on toast like butter. I opted for the smoked scallops and varnish clams in a bright, acidic espelette oil studded with bits of rutabaga and cabbage (espelette is a chili pepper with only moderate heat that’s used as the primary seasoning in Basque cuisine). I’ve never had a smoked scallop, and these, cut in thin discs, have the smooth, tender consistency of a raw scallop, though of course they are actually cooked. Here and there the pleasant jolt of a tiny, sweet clam joins the blend of earth and sea on the fork.

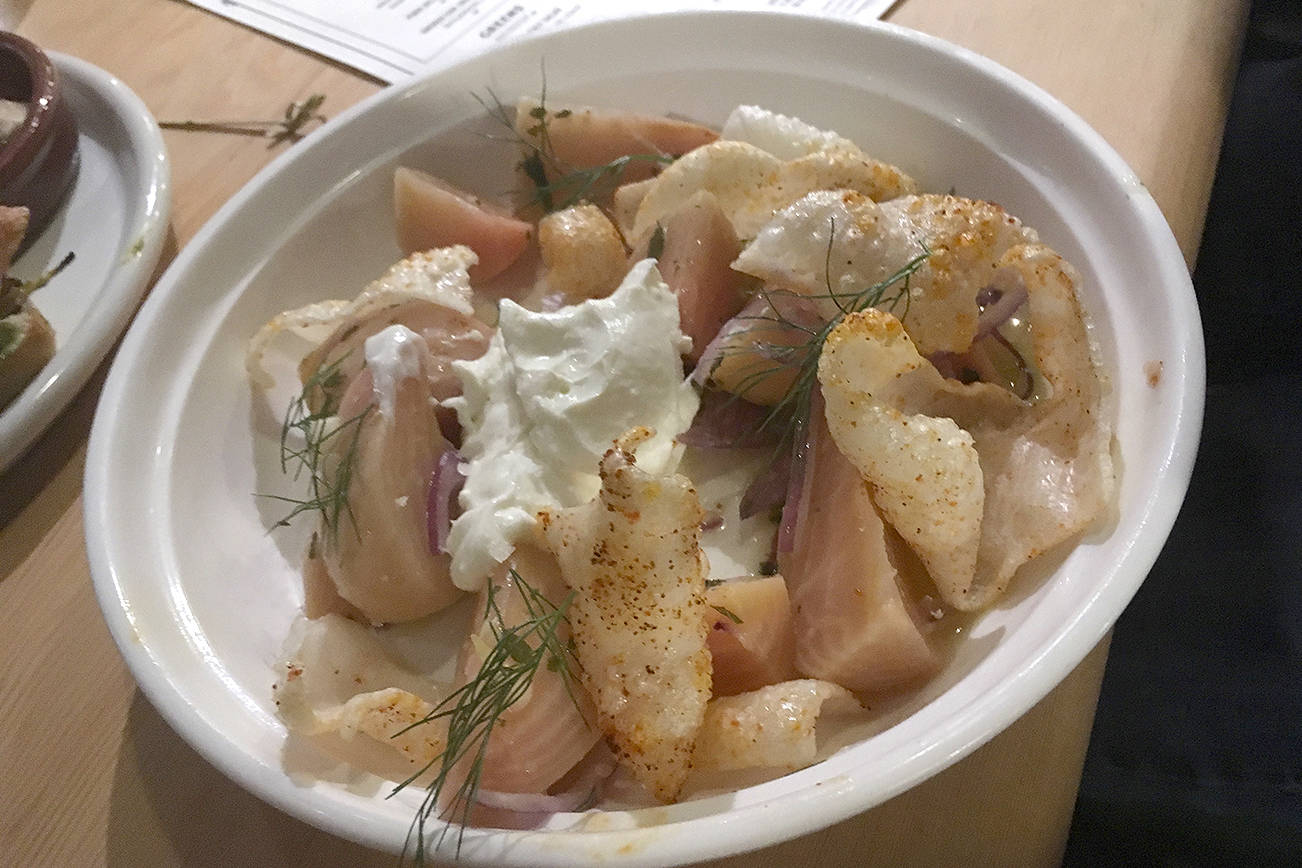

While L’Oursin’s scallops are unpredictably smoked, a typically smoked item, herring, here comes grilled instead. Two thin fillets from Alaska were delightfully tender and not the least bit fishy, unlike the herring I’m accustomed to. They’re served in a horseradish cream that manages to be light while still imparting its singular flavor—more like a broth than a cream, in which float thin ribbons of fennel and spheres of radish. It’s a great testament to eating lower on the aquatic food chain. A plate of grilled leeks comes in sizable chunks alongside thin pork-belly shavings, lusciously coated in a mustard sabayon and the leek oil that comes from charring the vegetable.

To round out the delicious smaller plates, we opted for two entrées. One was the roasted ling cod with radish, parsnip, hamhock beans (large corona beans), and a jambon de Bayonne (a French cured ham similar to the more familiar Spanish ibérico). The jambon is actually wrapped around the fish itself, which lies in, essentially, a smoky bean soup. The flavors are intense and lovely, though just on the precipice of eclipsing the taste of the fish. Every now and then my palate ferreted out the cod. The other was the poached Arctic char served with sunchokes, salsify, salmon eggs, and sea-urchin sauce. Skeptical about fish with fish eggs and uni sauce, I inquired about it before ordering, and the server assured us that it wasn’t very fishy. But although the fish is poached perfectly, to my tongue the dish was simply too briny, and we sent it back.

That blip was quickly forgotten, however, courtesy of the half chicken that, while not in the seafood realm that is the restaurant’s specialty, is a must-try. Served au vin jaune—stew-like in a hard-to-come-by white wine made from white grapes with green-skinned berries from the mountainous Jura area of France—it has a sherry-like flavor and is served with mushrooms and Brussels sprouts over a delicate, silk-smooth potato mousseline. Like everything on the menu, it’s seasoned pitch-perfectly—a rarity at even the best restaurants, where, inevitably, it seems, at least one item ends up under- or oversalted. I consider this a tremendous feat, which further enhances the intriguing, thoughtful menu.

The space, too, manages to give off that just-right lively French brasserie look, with yellow walls and elegant gold-rimmed chairs (the seats of which display lovely grained wood). Lots of mirrors and sconces and an inviting bar with the requisite chalkboard back on which drink specials are written in cursive complete it. The only difference: more room—with fewer crammed-together tables, the signature of this kind of French restaurant. If you know the type, you might be a little wistful for that bustling ambience; otherwise, you’ll simply appreciate the aesthetic and the space—and, more important, the all-around excellence that someone (besides Renee Erickson, who leans more toward room-temperature dishes and lighter fare) is finally bringing to a casual French dining experience in Seattle.

food@seattleweekly.com