In the memoir Down and Out in Paris and London, George Orwell describes a time in his life, before he gained fame for books like 1984, when he worked as a cook, suffering abuse from his head chef and enduring long, nearly impossible days of hard labor. The memoir is fascinating for its depiction of a young person coming up in the service industry and how, in the early 20th century, the job was damn close to slave labor.

The book is also a window into the life of a young writer struggling to exist in the world, at times confused and almost always broke. I read the book many years ago—when I was a little more confused and only slightly less broke—but I recently returned to it after coming across other examples of abuse and degradation in the kitchen: Anthony Bourdain’s scathing tell-all memoir Kitchen Confidential and the Netflix series Chef’s Table, in which famed New York City chef Dan Barber says, “Not that long ago, chefs were in the dungeons of the kitchens.” I wondered what it was like for Seattle chefs coming up as young cooks. Did they suffer some of the same abuses Orwell did, and how have working conditions changed over the past 75 years?

I asked three Seattle chefs of three distinct generations—Thierry Rautureau, Maria Hines, and Edouardo Jordan—what those early years were like, what they learned, what they had to endure, and how those experiences impacted their approach to cooking and coaching.

From a back corner booth in Loulay Kitchen and Bar, the downtown eatery Rautureau owns and operates, the James Beard Award-winning restaurateur sits with a hamburger in front of him, no bun, during the lull between lunch and dinner. Asked about the training he received as an aspiring cook in France, he makes clear his feelings about workplace abuse. “If you’re taking a 14- or 15-year-old kid, you’re supposed to be a teacher,” he says. “It’s just like the stuff that happened with the priests and sexual abuse; you have a person who you’re supposed to be teaching—and abusing that is a horrific thing.”

In 1973, at age 14, Rautureau finished his schooling and decided to take up a career in the kitchen. Working with food enticed him, and he knew it was a profession that could, and eventually did, take him around the world. But during his first apprenticeship in a French hotel, he met a frustrated boss who enjoyed inflicting mental and physical abuse on his employees.

“He was inept,” Rautureau says. “He wasn’t very good at taking the grind of the job. He struck us from time to time, slapped us around. Pans would fly through the air. One time I had a black eye and my mother asked, ‘What happened to you?’ and I told her I fell. Back then there was always the fear that your father or mother would hit you one back thinking you must have deserved the first one.”

Rautureau says he suffered a nervous breakdown after the first year. “I totally lost it,” he says. “I would never do this to anyone—I literally was shaking every day from the minute I got up at 7 o’clock in the morning to the minute I went to bed. It was really horrible. It messes with your mind, someone wanting to make you miserable. The [head chef] was built like a fucking armoire. There’s no way I could have touched him, he would have killed me.”

Rautureau managed to get away from that chef and went on to work in other hotels in France. Later he moved to the states, settling in Los Angeles before buying his first restaurant in Seattle 20-some years ago. Now he appears content, sitting in Loulay, as customer after customer and employee after employee smile and say hello when they see him.

Maria Hines, a James Beard Award winner and owner of Tilth, admits that her career, which started a couple decades after Rautureau’s, doesn’t contain any “Kitchen Confidential-type stories.” But, she says, she did struggle early on as a teenager working in both American and French kitchens. While she appreciates cooking culture for its “kinetic” pace and its creativity and diversity of people in the workforce, Hines, who worked multiple jobs while attending a culinary program in San Diego, was nearly overworked in the process. “Cooking is every single thing I did from the moment I woke up to the minute I went to sleep,” she says, “living and breathing my craft.”

Hines was determined to move here after learning about Seattle’s food scene from trade periodicals. She says she was impressed by our culinary culture and vastness of fresh ingredients. But before moving to the Northwest, she took a position on the line in France. “That was definitely the most challenging experience from a ‘how much can you handle’ standpoint,” she says.

She cooked 75 hours a week in a kitchen in Chambéry in exchange for room and board, she says. “They put me up in a non-insulated flat with one of those old army wiry cots with thick wool blankets and a light bulb that had a chain to turn it off and on.” After a week she was installed as a full-time cook and put on the service line, where she would run her station as tickets were called by the head chef. “I knew what he was calling out, but I didn’t know how many he was asking me to fire,” she says. “There was lots of yelling and screaming, frustration on his part, holding up fingers for how many orders. Then I took all the handwritten tickets off the spindle that night and translated—I learned the numbers up to 10, that way I could understand.”

She stayed there for three months with few people to talk to, “working my ass off. I had no money, so I’d hang out and drink really cheap wine in my cold-ass flat. It was lonely and it was hard.” Despite the difficulty, Hines, 43, says she recommends service-industry work to everyone. “You learn a strong work ethic, develop confidence, learn how to hold your own when things are really busy, learn how to work as a team, learn how to be organized and multitask, how not to complain and whine when it’s hard because it’s hard a lot. My advice for young people getting into the industry? Throw out the word ‘entitlement,’ just burn that word.”

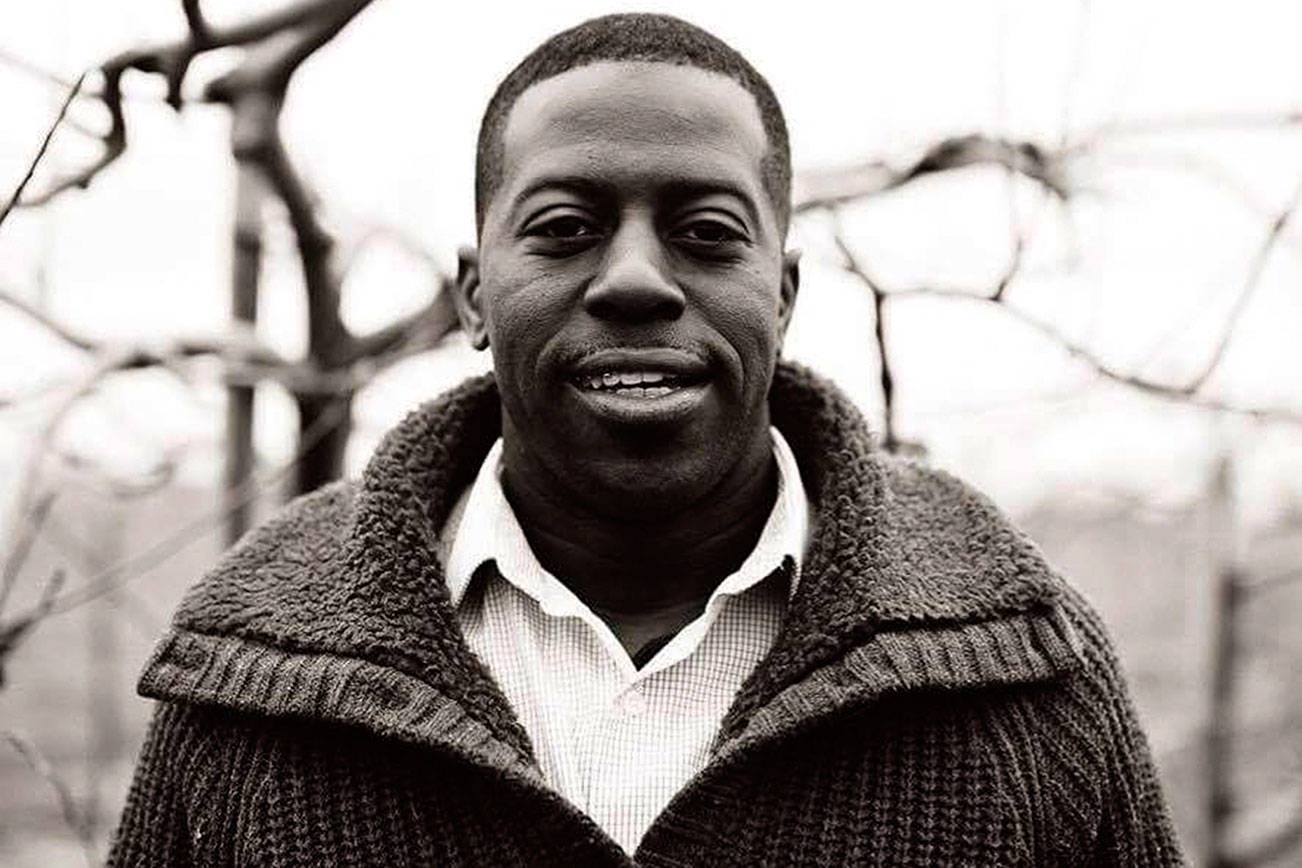

Edouardo Jordan, 35, the youthful chef behind Salare Restaurant in Ravenna, says he thinks things are a little easier for his generation than they were in the mid-20th century. Jordan, who started cooking at 9 with his mother in St. Petersburg, Fla., says he got serious about the profession after college. It was then he learned about the “intensity of cooking, mentally and physically,” like being on your feet 12 to 16 hours a day.

Instead of looking for a professional mentor, Jordan enrolled in Le Cordon Bleu College of Culinary Arts in Orlando after college. He intended “to get a better foundation,” though he admits that, given the chance, he might have done things differently. After finishing his training, he landed a job at Napa County, Calif.’s highly rated, Michelin-star-awarded French Laundry. “It was a well-oiled machine,” he says, “with some of the best cooks in the world.”

There was no physical abuse there, he says, no hitting or pot-throwing. “With our labor laws in the U.S., those things don’t really fly anymore,” he says. Indeed, laws have changed considerably in the last two decades alone. Now more than ever, kitchen workers are protected against wage theft, a lack of breaks in the workday, physical abuse, and sexual harassment from their superiors. Nevertheless, “there were chefs I worked for that were like sharks,” says Jordan. “They smelled blood and they attacked, they’d bark in your face and ride you hard for any minute mistake. I got yelled at—it didn’t send me home crying—but I was stressed. There are expectations you have to meet, time crunches, nothing’s ever right.”

But how did this stressful environment influence how he works with his cooks and other employees today? “You have to handle yourself as a leader,” says the young chef, who moved to Seattle from Florida with his wife, who is originally from the Emerald City. “I am just as tough on these guys as my chefs were to me, but I’m also like a father. I know how to shake a hand and have a beer with them at the end of the day. My goal is to have these folks be the best cooks and chefs in the city—to be able to walk into any three-star Michelin restaurant and stand next to these cooks and succeed.”