If the staff of the Italia Motel has an ethos, AJ—tenant, de facto security guard, and occasional crack smoker—has just articulated it. Brother to Mike, the Italia’s general manager, AJ had just hours before cast a wary eye in my direction as I pulled out of southbound Aurora Avenue traffic and into the motel parking lot. Tallboy of Natural Ice in hand, he then rejoined the growing crowd inside Mike’s in-motel apartment, followed closely by a diminutive but feisty prostitute affectionately referred to as “Li’l Bit.” Now sitting on the concrete step in front of Room 4, imparting nuggets of wisdom between sips of beer, AJ proceeds thusly: “Look here—everybody in this city has got a vice. But don’t nobody else care about that shit as long as you keep it to yourself.”

As if on cue, Keely, the room’s momentary occupant, bursts through the open door to escape the latest shouting match with Eric, her “old man.” It’s a cool Wednesday evening, and the pair has just run out of crack. Tan, with a raspy voice and a mound of scraggly bottle-blonde hair tucked underneath a blue trucker hat, Keely is one of the youngest and most put-together women walking the notorious Aurora Avenue stroll, which is not to say that crack addiction has left her unscathed. At 29, she looks harder than a person her age should. And Eric, who claims to be a former professional snowboarder, has the kind of drawn face one earns only by years of drug abuse and questionable life choices.

The couple had been flopping with an older man at the Hotel Nexus, a 10-minute drive north and, luxury-wise, half a world away from the fading structures that dot Aurora from the ship canal to North 46th Street. But Keely and Eric’s host up and disappeared, taking the entry key with him and forcing Keely to return to Aurora, where she accompanied her friend, a stick-figure brunette named Mercedes, as she trolled the strip for johns.

Keely claims she isn’t a prostitute, just a middlewoman. For a cut of her client’s take, she’ll facilitate a “date” with a pro, or hook up a potential buyer with crack, marijuana, speed, or any of the various other social lubricants available along the Aurora corridor.

On this evening the couple’s need was shelter, which can be had at the Italia for $50 a night. That secured, Keely takes to the bathroom, produces a small white pebble of crack from her sweatshirt pocket, and begins packing it into a thin, smoke-stained glass tube. Her eyelids close as she draws in the smoke. Less of an enthusiast than his girlfriend, Eric takes one hit, then backs off. On this night at least, his vice of choice is beer.

Eerily calm for a person who’s just taken a mighty rip from a crack pipe, Keely moves toward the door and the waiting strip. It was relatively early, and there was more crack money to scare up.

Room 4 is arguably one of the Italia’s nicest—but that doesn’t mean it’s nice. Unforgiving light from the ceiling fixture makes the walls appear a shade of white normally seen only in the complexions of terminal tuberculosis patients. And there’s a hypodermic needle on the counter next to the bathroom sink, a forgotten remnant of some previous tenant’s stay. Keely and Eric argue while navigating the narrow path carved by a thin double-size mattress lying atop an even thinner box spring resting on the bare floor.

As she gets up to leave, Keely doesn’t let Eric know where she’s going, or whom she’s going to be with. Nor does she have a cell phone to call him in case something goes wrong. Eric accuses her of fudging the truth about not turning tricks. “There are better ways to make money,” he says.

Red-faced and still riding a crack-induced high, Keely replies: “Well, you’re not gonna fucking go out and do it, are you?”

AJ, Keely’s occasional smoking partner, shoots Eric a pitying look as Keely storms out. AJ shakes his head and gets up to make his rounds.

After years of complaints from neighborhood residents and hundreds of calls to the police for service, the city has declared war on the seedy motels of Aurora Avenue North—five of them, anyway.

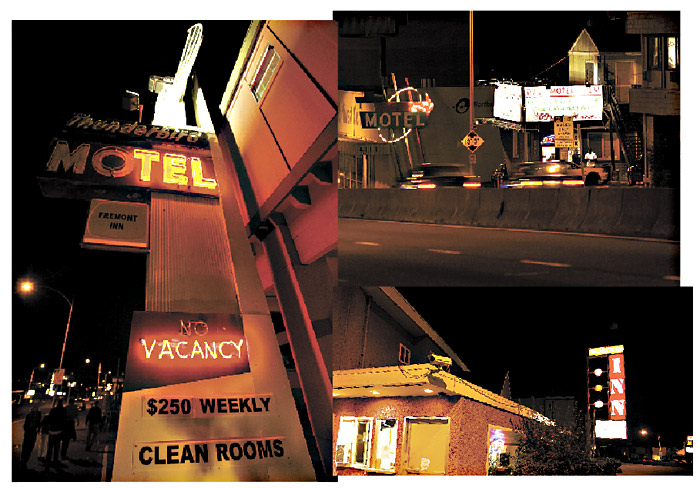

The Italia, along with its conjoined twin the Isabella, the Fremont Inn (formerly the Thunderbird Motel), the Wallingford Inn, and the Seattle Motor Inn (better known by its former name, the Black Angus Motel) have since 2007 all been owned and operated by Dean and Jill Inman, a Bothell couple whose business licenses the city of Seattle now seems determined to revoke.

On August 21, the Seattle City Attorney’s office filed 152 criminal charges against the Inmans for what it classified as a “variety of tax violations.” As of August 31, the city had not yet determined exactly how much in back taxes the Inmans owe, but court documents indicate that shortly after they purchased the properties—all of which, save for the more northerly Seattle Motor Inn, are located within a five-block area just north of the Aurora Avenue Bridge—the Inmans began to either fall behind on, or simply neglect to pay, a litany of municipal taxes.

The Inmans have also managed to fall behind on their electric bills. Last week, city officials threatened to cut off electrical service to all five of their motels, citing the $38,000 owed the city for utilities. The Inmans subsequently paid the required minimum of $11,000, but only after city outreach workers and police officers began knocking on doors at the motels to inform residents that they would soon be cutting off the juice. Then there is the still-unresolved matter of crime. Aurora has long had a reputation as a haven for drug sales, prostitution, and other criminal activity, and city officials and residents of the increasingly posh neighborhoods near the motels both say the problems have only worsened since the Inmans took over.

Officials began meeting with the Inmans in 2008 to come up with a solution to curtail the criminal activity around their properties, but say the Inmans have ignored the problem. “We’ve been attempting to work with them for a number of years, to no avail,” says Alex Fryer, a spokesperson for Mayor Nickels’ office. “We want to see an improvement in the public-safety aspect of the neighborhoods surrounding those businesses, and an improvement in the conduct of the businesses themselves.”

Days after the city brought down the hammer, however, illicit transactions and those who facilitate them remain.

The Inmans would not directly field questions related to this story, instead choosing to release the following statement through their attorney [this is an excerpt of that statement; see the full text here]: “My response to the charges is that of bewilderment, confusion, and disbelief that the city intends to use such force and scare tactics to close my legally operating businesses. I have always made myself very available to the city, the police department, and the neighbors to discuss any of their concerns. I have not received any complaints, phone calls, or e-mails for a very long time indicating anyone was concerned about any of the properties…People come to low-rent motels after evictions, on public assistance, with children, who are homeless—and oftentimes this type of shelter is someone’s last stop before sleeping on the street. To be sure, there are problems on Aurora and my motels are not The Four Seasons, but I see it day in and day out: There is a great need for this type of shelter.”

“Criminal activity at the motels is simply not tolerated,” the statement continues. “The police are called and suspicious activity is reported, left to the proper authorities to handle…When someone purchases a room for a night, they have also purchased privacy and the space is theirs to use. Should they choose abuse drugs or alcohol behind their door is out of my control. I simply will not discriminate and have had many conversations with the City and the police to this effect.”

Spencer Anderson moved into his century-old colonial in 2006, the year before the Inmans closed the deal for the Italia and Isabella, both of which are within spitting distance of Anderson’s property line. The previous owners had run the facilities as apartment complexes, he says, renting mostly to college students. “It was illegal, but it made for a safer neighborhood,” recalls Anderson.

Then came the Inmans.

Both Anderson and Erik Pihl, transportation chair of the Fremont Neighborhood Council, recall that initially the Inmans said all the right things. According to Pihl, a meeting held shortly after the Inmans purchased the Wallingford Inn turned into a love-fest, with the couple assuring concerned neighborhood residents that they planned to operate in a responsible manner. As renovations to the Wallingford Inn began, the lettering on the marquee out front read “The Party’s Over, Under New Management.”

But despite the promises, residents say criminal activity continued. “They said they were going to run a clean operation, but that quickly went out of the window,” says Pihl.

In the months that led up to last month’s crackdown, police, representatives from the City Attorney’s office, and neighborhood residents all sat down with the Inmans to discuss the issues at their motels. When that proved fruitless, says Anderson, a loosely organized group of members of FAWN (Fremont and Wallingford Neighbors) and other neighborhood residents came up with a plan to drive the Inmans out of business with a flood of lawsuits, a move allowed by state nuisance-property law. However, municipal officials advised against it, asking the group to hold off while the city pursued its own resolution.

In 2007, Mayor Nickels launched his “Clean Up Your Act” program. While not targeted directly at problem motels or their owners, the program was intended to give the city more leeway to penalize owners who allowed their properties to slip into significant or hazardous disrepair. Unfortunately for residents living near the Inman motels, the program is driven by complaints from residents of the properties, not neighbors, and according to spokesperson Bryan Steven of the city’s Department of Planning and Development, the agency charged with enforcing building-code violations, the city has not received a complaint from any tenant of the Inmans’ five properties since they took ownership in 2007.

City Councilmember Tim Burgess, who chairs the council’s public safety committee, is currently in the process of drafting a new ordinance that would allow the city to revoke the licenses of business owners who are found to allow criminal activity at their properties. Meanwhile, although police make trips aplenty to the motels, the seedy atmosphere persists. Around the corner from Anderson’s house can usually be found a line of steam-filled cars gently rocking in the night. “It’s not something you want to see while walking the dog,” he says.

In Pihl’s estimation, the Inmans don’t feel as if they know how to curtail the shady activities occurring at their motels, nor are they all that interested in trying. “It’s a matter of strong management,” says Pihl. “As far as we can tell, they’re not close to the hotels. And to deal with these issues, you have to be present.”

The city’s recent crackdown may force the Inmans to pay more attention. In the meantime, says Anderson, the couple should “pay for properly trained security. I realize that money is an issue, but as far as we’re concerned, if you decide to buy five hotels on North Aurora, you know what you’re getting into.”

The Marco Polo Motel stands as an example of the sort of tightly run ship Anderson is talking about. Pull into its parking lot and you’re treated to a reminder of a bygone era, when the construction of Interstate 5 was decades off and weary travelers on Highway 99—then the West Coast’s chief north-south route—were drawn into auto-courts and motels by large neon signs.

Unlike the Italia, which is located directly across Aurora, the Marco Polo still has a sign that works. Inside the office, the day manager, a middle-aged Asian man who declines to give his name, describes in a heavy accent why the Marco Polo seems immune from the problems that plague the Italia.

“We don’t tolerate it,” he says. “When we see something going on that shouldn’t, we kick those people out. And they know they can’t get away with it here.”

“You are at the center of the world, bruh.” Charles, a recently hired Italia employee, says as he leans against the door of his green sedan parked in front of the motel’s office. “They got crack bitches, dope-fiend bitches, pimps, pussy, crank, coke, weed; whatever you want, you can get it right here.”

Minutes ago, a man carrying a gold bowling bag walked silently up the stairs and disappeared into a corner room. Moments later, he leaves just as silently as he came, sans bag. Over his glasses, Charles shoots a knowing look.

There are at least two species of guests at the Inmans’ motels: permanent residents who pay by the week, and those who need a warm place to spend the night (or, depending on their needs, only an hour or two). Charles is part of a third group: Employees who stay in the motels rent-free. He arrived in Seattle nearly a month ago after fleeing Manhattan, Kansas, and the woman who had just become his second ex-wife. He later caught on at the Seattle Motor Inn, which he says was at one time the worst of the Inman motels.

“There were drug dealers hanging out on the balconies and slangin’ right out in the open,” he says. Police documents bear that out. According to reports, there were 168 calls for service to the 12200 block of Aurora, where the Seattle Motor Inn is located, from January to July of this year. But that still pales in comparison to the criminal way station that is the Italia/Isabella/Fremont Inn triumvirate. During the same period, police were called to the 4100 and 4200 block of Aurora 289 times.

In April 2008, Seattle police made 32 arrests at the Inmans’ motels, seizing 11.7 grams of marijuana, 42 grams of cocaine, and four drug scales—all within the span of 16 days. And in the early hours of August 1, a guest staying in Room 19 at the Fremont Inn stabbed another man after he had refused to stop banging on the door. (The victim lived, according to police reports.)

The 15-room Isabella is technically run as an apartment complex. Though larger, the rooms are in no better shape than the Italia’s, a fact cited by one occupant as the reason that she and her family are moving out.

Sabrina Rene, along with six other members of her extended family and an indeterminate number of pets, lives in a one-bedroom apartment on the Isabella’s ground floor—but not for much longer. Rene moved in a month ago, joining the rest of the clan after a 15-year stint living in Alaska. Relatively cheap rent ($1,100 per month) and the inability to muster enough cash for a security deposit on a proper residence have kept the family there since February, she explains. But they’ve recently found a landlord willing to forgo requiring a deposit in exchange for their work in renovating a three-bedroom West Seattle house the family plans to move into later this month.

“This isn’t an ideal place for a lot of reasons,” says Rene, standing among pet cushions and patio chairs, one of which contains her snoozing father-in-law, that have spilled out from the apartment and onto the balcony. “It’s not a big enough space for this many people. And there are all kinds of issues with the apartment that need improving, but there’s so much drama around here with the fights and the shootings that the manager can’t get to them because he’s so focused on trying to keep control.”

Rene herself once worked as a hotel manager in Aberdeen, Wash. Much of her time, she says, was spent contending with the pushers and prostitutes who frequented the place. “It was bad,” Rene reminisces. “But maybe not as bad as this.”

Inside the office that the Italia and Isabella share, Mike, general manager of both properties, holds court.He’s dressed like a teenager—oversized black T-shirt, baggy jeans, wool skullcap—but with his graying stubble looks to be in his mid-40s. In an easy Southern cadence, Mike imparts the intricacies of the check-in process to a new female employee ensconced behind the front desk with a bottle of Mike’s Hard Lemonade. Towering over her, Mike appears almost grandfatherly.

His transfer south from the Seattle Motor Inn is recent. At the behest of the owners, he recently moved into the apartment connected to this office, thereby making him manager, handyman, and chief security guard. According to his brother AJ, Mike is not shy about throwing punches when necessary.

None of the employees can say with certainty how many physical altercations occur at the motel. But do they happen often? Says Charles, with a grin: “Is a pig’s pussy pork?”

At 11 p.m., the foot traffic around the Italia slows to a trickle, as curfew has taken effect. Guests retreat to their rooms with whatever entertainment they’ve secured for the evening, and the college dorm–like atmosphere that was ceases to be.

Out of a combination of worry and frustration, Eric decides to search for Keely, who still has not returned to the room. Before he can shut the door, Mike, standing on the stoop outside the front office, issues a warning. “Y’all can’t hop from room to room, they’re trying to shut us down,” he says, nodding in the general direction of what may or may not be a police surveillance van parked at the Marco Polo across the street.

Eric nods in affirmation, but presses on across the avenue. At this late hour, it’s grown quiet enough to safely—albeit illegally—cross the normally busy, high-speed thoroughfare. Eric is headed to see Johnny, an ex-convict who stays at the Wallingford Inn a few blocks north. If Keely were looking to score, she might end up there, Eric says, or rent a $60 room of her own “just to piss him off.”

For the prospective tenant whose preferred diversions require some level of secrecy, the Wallingford Inn has one distinct advantage over the Inmans’ four other motels: Most of its rooms face away from Aurora, rendering them invisible to passing traffic. Inside his second-floor apartment, Johnny is wired. Stocky, shirtless, and covered in tats, he flits around the room, pausing only to puff from his crack pipe and groove to the blues-rock pouring from the speakers. He hasn’t seen Keely, he says, and after taking a last pull on his pipe, he exits, leaving Eric on the couch to ruminate on his predicament.

Prior to moving to Seattle, he and Keely lived on a houseboat in Tacoma, which they lost due to what he explains was the latest in a “long line of fuck-ups.” Covered head to toe with a variety of colorful, intertwining tattoos, Eric claims he was once sponsored by the likes of snowboarding outfitters K2 and Burton. Then he went to prison on a narcotics bust, but not before he lost his sponsorship to Oxycontin addiction and what he calls “general asshole-ish behavior.”

In January, he woke up in a hospital bed, not remembering how he’d gotten there. An overdose of Oxy had done the job. He decided then that he and Keely were going to get clean, he says. Eight months later, they are stuck bumming lodging from strangers.

With his head dangling over the back of the couch, Eric admits that if not for Keely, he’d have gotten his shit together a long time ago. He’s had enough. His parents have begged him to return home to Snohomish County, where they’ve guaranteed him shelter and a decent-paying job. But what would that say about him as a man, he asks, if he were to ditch Keely while she’s struggling with her own addiction when she remained at his side while he struggled with his?

Hours later, Keely materializes, trying to elude Mike on her way to the Isabella. A sleepy Mike lets her slide with a weary shake of his head, and Keely walks up a flight of stairs into the dark of Room 28.

Mercedes has returned from her “date” and is sitting on a bed in the back room. Keely retreats to the bathroom for another hit of crack, and the smoke wafts gently into the bedroom. In the dim light, it’s clear that Mercedes, like her friend, has remnants of beauty. But her attitude has gone foul, and her face is gaunt. There’s sleep to be had.

Just before sunup, Keely returns to Room 4, where she and a waiting Eric fly into yet another muted argument. A car horn sounds outside, and Mike, roused from his apartment, stands outside the office door with an aluminum baseball bat resting on his shoulder. Keely runs out the door into the car’s passenger seat, and it speeds out of sight. Eric shakes his head, pulls down his ballcap, and returns to bed.

An hour later it’s daylight, and Keely still hasn’t returned. Still reeling from their last crack-fueled argument, Eric is resigned to leaving her to her adventures, adding the obvious: “There are a bunch of scandalous motherfuckers living in these hotels.”