THE MOST STRIKING THING about Musicology (NPG/Columbia), the first Prince album available at brick-and-mortar “wrecka stows” (his term, from 1986’s Under the Cherry Moon) since 2001’s The Rainbow Children, and the subsequent U.S. tour that comes to KeyArena this Monday and Tuesday is that they constitute the ultimate rarity in his career lately: an event. For a while there, everything the guy did was an event—Dirty Mind shattering taboos as much musical as lyrical, Purple Rain the world-swallowing phenomenon, single after single remaking what you could get away with on pop radio, Sign ‘O’ the Times the last great R&B album before hip-hop began its wholesale hijacking of pop music, black and white alike.

Obviously, Prince got used to this. He spent much of the ’90s acting as if he were still an event maker, even as the actions—from the name change to writing “Slave” on his cheek in eyeliner to issuing a triple CD to a world that had barely nibbled at the two separately released discs he’d put out in the 14 months before—seemed less and less significant. His faithful fans were rewarded with a lot more good music than he was commonly believed to have made during that period—1995’s The Gold Experience and ’96’s Emancipation, the aforementioned triple, are a lot better than their reputations would suggest.

But when he returned with 1999’s cameo-festooned, completely unmemorable Rave Un2 the Joy Fantastic, and then the disastrous Rainbow Children (a preachy concept album about the Jehovah’s Witness faith that sounds like Kenny G—excuse me, that’s Najee, his Afro-American counterpart—soloing all over it: what a great idea!), even someone who adores Prince as much as I do had to get off the bus. By contrast, Musicology‘s strategy is . . . surprise! There is no strategy! It announces itself by not announcing itself at all. Musicology is just Prince, making Prince music (meaning by himself, mostly), all in that old-fashioned Prince style we all used to love so much. Remember that?

Actually, you probably won’t, at least while this album is playing—except when he deliberately quotes himself, that is. The bridge of “A Million Days”—”It’s only been an hour since you left. . . . You’re the perfect picture of what love should look like”— recalls both “17 Days” and “The Beautiful Ones.” Even the chorus of “Call My Name” is self-referential: “I just can’t stop writing songs about you,” he sings, in self-mocking acknowledgment of both his compulsive nature and his reputation for repeating himself—which he does later in the chorus, with the lines “I know it’s only been three hours/But I love it when U call my name” echoing “A Million Days.”

But while it’s easy to compare the sonic sparseness of Musicology to minimal classics like Dirty Mind, Sign ‘O’ the Times, and 1986’s “Kiss,” the new album sounds nothing like his earlier work. Indeed, a lot of it is rooted more in his ’90s work than his ’80s. The title track is a variation on the spare groove of “Sexy MF,” from 1992’s I’m Going to Change My Name to the Title of This Album (And Lose Most of My Fans in the Bargain), which itself was based primarily on late-’60s James Brown numbers like “Ain’t It Funky Now.” Many of Musicology‘s bass lines are slapped and plucked, a style that Prince has utilized since early in his career, but even more so as he began moving away from the colder, electronic textures that marked his ’80s work in favor of the looser, jammy style of more recent albums. It also seems reasonable to credit part of this shift to Prince’s long association with Larry Graham, the former Sly & the Family Stone and Graham Central Station bassist and current Jehovah’s Witness, whom Prince has credited with indoctrinating him into the faith.

That faith was what Prince was most famous for not long before Musicology‘s release. In October of last year, the Minneapolis Star Tribune, the newspaper of Prince’s hometown, reported that he’d been knocking on doors in the Minneapolis suburbs, accompanied by Graham. On Yom Kippur, the most important holiday on the Jewish calendar, Prince and Graham visited a Jewish couple in the suburb of Eden Prairie during a football game, staying 25 minutes and leaving the couple a pamphlet. The famous visitors were unfailingly polite, but the couple was annoyed—the Minnesota Vikings had just gained possession of the football, and they missed the action.

For a while, the account of this event was one of the most-forwarded e-mails in the music industry; I received it no less than a dozen times, usually from people who knew I had just finished writing a short book on Sign ‘O’ the Times. Having just expended a huge amount of energy in a comparatively short time to finish writing 28,000 words about him—about an artist whose work has been more crucial to me in more ways than nearly anyone else’s—I found the e-mails depressing. This honest expression of faith, however ill advised or timed, seemed to cement Prince’s reputation as a has-been.

Even if Musicology wasn’t made to specifically ward off that perception, it’s certainly been marketed that way. Prince is his own man, always, and if he appears calmer and more relaxed than ever on this album and in his public appearances, good on him—it certainly doesn’t seem pernicious. But it is calculated, and it has largely worked. That, and the fact that along with the Pixies’ reunion and people actually taking Morrissey seriously again (it was a mistake the first time, people), Prince’s new surge is evidence of ’80s revivalism—particularly ’80s college-rock revivalism—at its baldest.

It’s also just desserts, because even if he’d kept knocking on doors and done nothing else, Prince has already been everywhere over the past few years. Alicia Keys turned his old B-side, “How Come U Don’t Call Me Anymore,” into a hit in 2001; the Neptunes’ nimble funk-and-roll is unthinkable without Prince’s example—listen to their production of No Doubt’s “Hella Good,” Jay-Z’s “I Just Wanna Love U (Give It to Me),” or Britney Spears’ “I’m a Slave 4 U,” for starters. Basement Jaxx’s and OutKast’s most recent albums pay such explicit homage to the guy (Jaxx’s “Right Here’s the Spot” name-checks “Delirious” and “All the Critics Love U in New York,” while “She Lives in My Lap” pays Sign‘s “The Ballad of Dorothy Parker” the sincerest form of flattery) that they practically owe him royalties.

The critical plaudits that have greeted Musicology seem out of proportion with the modesty of its actual music. Part of that has to do with the goodwill that he’s accrued just by getting famous again—finally, a maker of fun music the press can take seriously. (I will love calculated, pre-tested, manufactured pop as long as I draw breath, but anything is better than Hillary fucking Duff.) Still, everyone else has weighed in on the title track’s most eyebrow-raising line, so let’s try it ourselves, shall we? “Wish I had a dollar 4 every time U say/’Don’t U miss the feeling music gave U/Back in the day?'”

Well, I certainly miss the feeling Prince’s music gave me back in the day, though the feeling Musicology gives me, as muted and mild as it frequently is, isn’t too bad, either. But I’m not feeling especially cynical about music right now, even though most of what crosses my desk is mediocre to horrid. I am, however, pretty certain that the kind of musical conservatism Prince gives the rah-rah to here is something I’d prefer to leave as far behind as possible.

That conservatism was presaged by the many comments on 2002’s three-disc concert box, One Nite Alone . . . Live!, and last year’s Live at the Aladdin Las Vegas DVD to the effect that we’re hearing “real music” played on “real instruments,” which is pretty ironic coming from a guy who as much as anyone popularized the use of drum machines and synthesizers in pop. It’s what’s most disappointing about Musicology. But to some degree, it’s also what’s most satisfying about it. Over the last dozen or so years, Prince has become a chopsman, valorizing technique over ideas, but for the most part, Musicology keeps the instrumental flourishes as straightforward as the melodies.

My favorite song on the album isn’t one that’s been talked about much in the reviews I’ve seen. “What Do U Want Me 2 Do?” sounds at first like an afterthought. It’s a simple pop song with a popping bass line, airy drum machine programming (like a sparer “Ballad of Dorothy Parker”) abetted by what sounds like live cymbal work, and jazzy guitar. The lyrics find Prince the happily married musician spurning an advance from a fan: “Can’t U see this ring?” Like most of his best later work, it breaks no ground. But it’s enough to make you wonder what the album he’s allegedly planning to record for Blue Note might be like. If nothing else, the fact that there’s a reason to look forward to a new Prince album feels like its own reward.

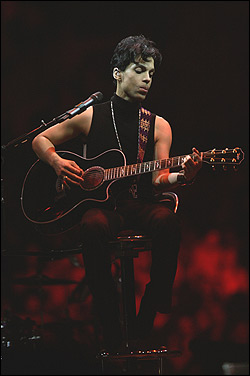

Prince plays KeyArena at 7:30 p.m. Mon., Aug. 30–Tues., Aug. 31. $49.50–$75.