When the resources are available, artists frequently turn to the creation of spectacle, from the majesty of sacred architecture to Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s surreal interruptions of landscapes. At its most useful, spectacle grabs attention and directs it to a profound question (or an easy answer, in the case of propaganda). At its laziest, its scale alone provides the majority of the content (e.g., a lot of large inflatables from the likes of Paul McCarthy and Jeff Koons).

The monumental form reflects a monumental ego, and even when it offers audiences some participatory or immersive effect, it satisfies only a hunger for a novel experience, an egoic pursuit of its own. Of course, the experience isn’t complete without getting hard, Instagrammable evidence of the event and sharing it to one’s networks, where it might conceivably set one apart and satisfy the capitalistic call for individualism—just like thousands of others who had the same experience.

All this tension around and desire for spectacle and novelty makes Yayoi Kusama’s Infinity Rooms a quintessential artwork for our time and Kusama herself its quintessential artist. It is no wonder that during its two-year tour, an exhibition of her Infinity Mirrors (ready to open at Seattle Art Museum this week) has been selling out almost as soon as tickets are available. If you are lucky enough to already hold a ticket for the show at SAM, congratulations. If not, you might still get one if you go early enough in the day during the week. Limited tickets will be released each morning. For those who don’t know Kusama’s work, the obvious question is “Why all the buzz?”

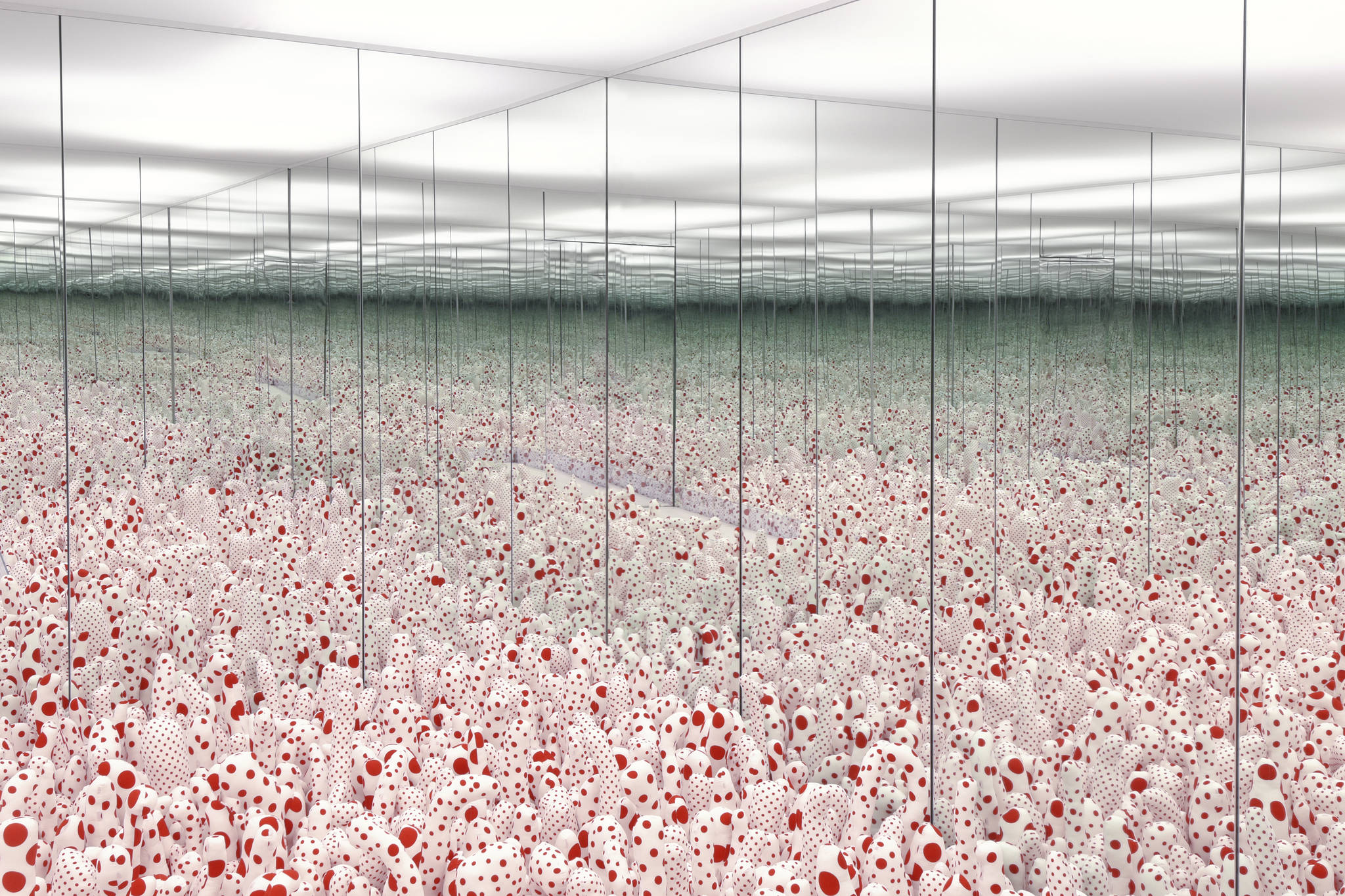

Kusama’s Infinity Rooms are a unique sort of spectacle because they turn the typical model outside-in. Rather than relying on large-scale forms, they are small structures that create the illusion of infinity— mirrors on all sides and hanging lights or masses of sculpture on the floor to further confound the sense of depth. The added twist is that if you step back far enough, even the largest structure reveals itself to be finite, whereas you can never penetrate to the end of a small Infinity Room.

This notion is what ties the Infinity Room format to Kusama’s other calling card: dots. The earth itself is a dot. Everything is a dot. In Kusama’s worldview, everything is atomized into dots in an incomprehensibly large universe, and the sense of a singular continuity (i.e., ego, monument, institution) is “obliterated” by her dots. For example, in the manifesto supporting her 1968 performance series, The Anatomic Explosion, staged across from the New York Stock Exchange, Kusama exhorted in all caps: “OBLITERATE THE MEN OF WALL STREET WITH POLKA DOTS ON THEIR NAKED BODIES.” She made such proclamations while spray-painting dots onto nude dancers. Now she designs dotted iPhone covers and T-shirts. Look for them in the gift shop.

To note Kusama’s acquiescence to the charms of capitalism over time might seem sardonic, because if Americans crave anything more than novelty, it’s authenticity. A challenge to Kusama’s authenticity would be as dull to read as a hagiography of her. There is no shortage of the latter. The art world cannot completely shed a sense of religiosity, and Kusama’s voluntary commitment to a mental hospital (since 1977) and her lifelong aversion to sex is a perfect modern analogue to monasticism. Critics have even dubbed her “the high priestess of polka dots.”

We neither need praise nor suspect Kusama. The Infinity Rooms speak for themselves, in many ways. The real critical query should be into how they are turned back into mere spectacle for its own sake—something simplistic, or even solipsistic.

Kusama’s “All the Eternal Love I Have for the Pumpkins.” Courtesy SAM

Kusama’s paintings debuted stateside in Seattle in 1957, at Zoe Dusanne Gallery. She soon moved to New York, where she was embraced by the likes of Georgia O’Keefe and her large paintings were compared with those of Jackson Pollock. Such comparisons grossly missed the point, though they didn’t hurt her career. Whereas Pollock’s action painting emphasized performative creation, Kusama was already trying to capture infinity with repetitive strokes that suggested endlessness beyond the edge of the canvas. This use of abstraction to point one’s mind to infinity dates back at least as far as Islamic art, but also had kinship with some of Kusama’s contemporaries, notably Agnes Martin.

In the early 1960s, Kusama started making soft sculptures (generally phallic, dotted forms) which she would arrange in groups she called “accumulations.” That was also the peak time for “happenings” in the New York City art scene. Happenings are at base a performance, but because they involve the audiences in ways that feel spontaneous, they break the barrier between artist and audience within the artwork itself.

In a conceptual climate that sought to directly involve audiences, the creation of Kusama’s first Infinity Room in 1965 was a logical next step for the artist: total immersion in a glimpse of infinity. That room, Phalli’s Field, was brightly lit and filled with one of her phallic accumulations. A famous photograph by Eikoh Hosoe shows Kusama sprawling among them in a skin-tight red outfit.

Contrast that with a newer work, The Souls of Millions of Light Years Away, which is lit only by hundreds of small, glimmering lights, placing viewers in what appears to be an endless sea of stars. It’s not the best place for a photo op, but that won’t stop people from seeing it primarily through their phone, if my past observations are any indication. What a journey! The illusion of infinity is created within a small box, and then reduced again to a finite, pixelated image, ready to be hashtagged and shot into the cloud. And reflected over and over, receding into the void, the image of the self as visual echo shouting: “I’m an individual… I’m an individual… I’m…”

Kusama’s “Aftermath of Obliteration of Eternity.” Courtesy SAM

Kusama’s “Aftermath of Obliteration of Eternity.” Courtesy SAM

It is often noted that any artwork is as much a mirror as a window. Kusama makes this literally so, and given that you have only 20 to 30 seconds in an Infinity Room before the docent shuffles you out and brings in the next group of two or three viewers, chances are you will not have time for a real epiphany. What you see in there will already be a reflection of where you are. If you are already the pensive sort who can’t help but ponder everything between the microscopic and macroscopic, these rooms are a beautiful, memorable visual aid, but unnecessary; you already have the self-negation thing down. If you are an egoist, you’ll find yourself in the most magical dressing room, with your favorite person in every direction. No need for a selfie stick. It’s panoramic you (and two other people).

But if you are a child (or are able to step back into a childlike state), I say go go go. You’ll probably spend two hours in lines for a few minutes of wonder, but that’s more than one gets out of a feature-length film—and unlike in a theater, it is acceptable to talk with your neighbor during the dull parts. And if you are in love, go. This may sound schlocky, but it’s the truth. After all, the Infinity Rooms are simultaneously self-negating and self-centering, just as Kusama’s dot motif sees a unified whole among discrete particles. Isn’t that a fine definition of love between humans?

Go with someone you love: parent, child, lover, friend. Instead of holding up your phone and looking at a pixel of infinity, hold their hand and commit the moment to your own memory rather than the cloud. After all, as long as we’re here on this pale blue dot, what do we have to connect with but each other, the closest image we have of the divine? The rest is just… dot dot dot. Yayoi Kusama: Infinity Mirrors, Seattle Art Museum, 1300 First Ave., seattleartmuseum.org. $35. Fri., June 30–Sun., Sept. 10.

visualarts@seattleweekly.com