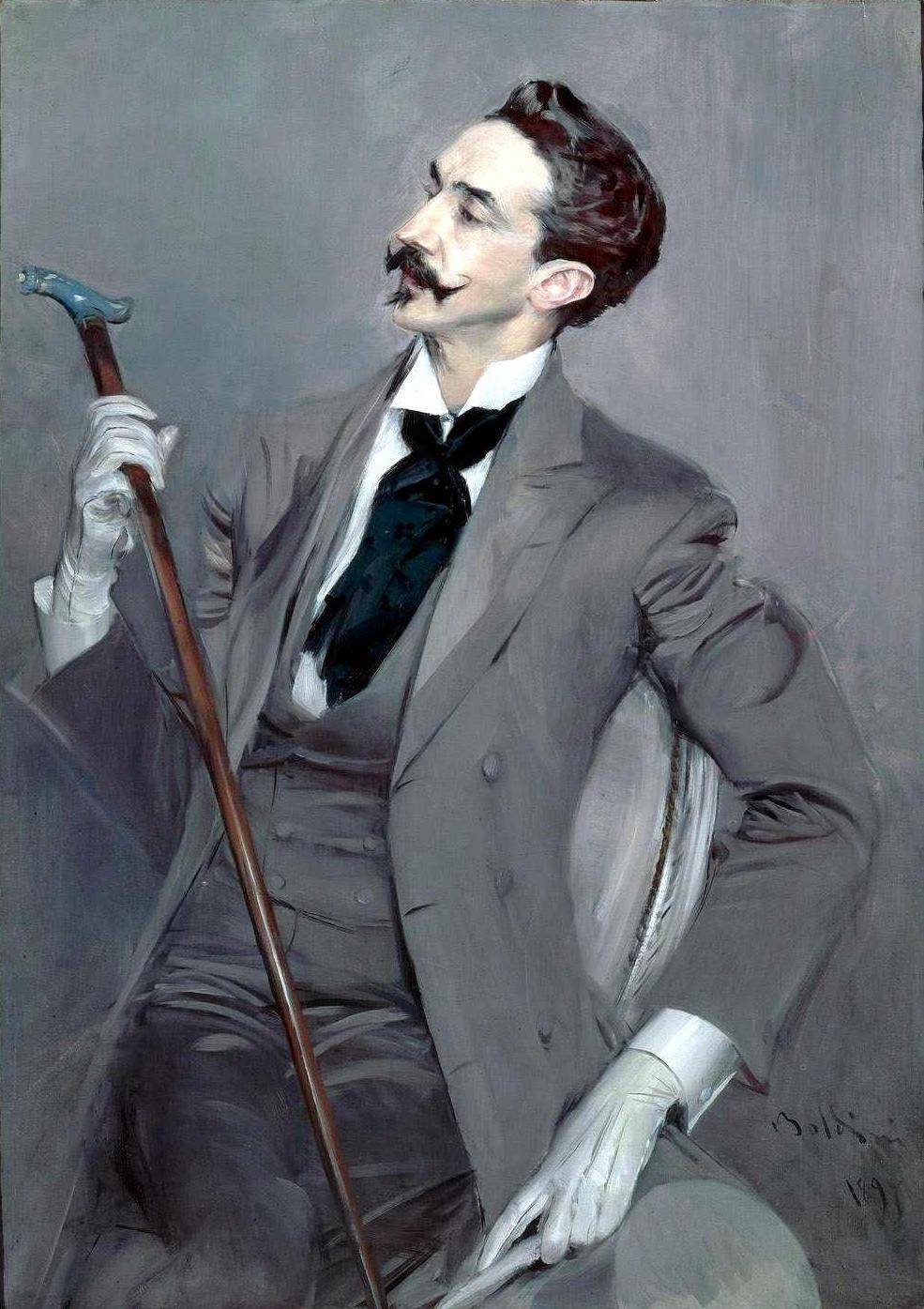

“Jeez, he looks familiar,” I thought at first glance of Brandon J. Simmons, a cast member in Book-It’s production of Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray. Not because I’d seen him elsewhere on- or offstage, though he keeps busy in Seattle as an actor, director, and writer. I recognized Simmons from a book cover: a paperback edition of Wilde’s plays, which turns out to be a portrait of poet Robert de Montesquiou (1855–1921). Draped over a round-backed chair, impeccably dressed and mustachioed, with an air of amused hauteur—it’s too deliciously similar to be coincidence. Isn’t it?

Though they were the same age and Wilde frequented Paris, there’s no record Montesquiou ever met him, and no reason to think Wilde had him in mind when he created Lord Henry Wotton, the role Simmons plays—stunningly—in Picture. Wilde didn’t need a model; there’s a Wottonlike character, the upper-class dandy who gets all the wittiest lines, in practically everything he wrote, and considering Wilde’s own reputation as a brilliant conversationalist and epigrammatist, the Wottons in his plays are alter egos as much as anything else. (He admitted as much, saying that “Lord Henry is what the world thinks of me.”)

Montesquiou is, however, said to be the model for someone else—the period’s most decadent fictional character, Des Esseintes in Huysmans’ A rebours (1884). It tells the story of a hypersensitive, easily jaded nobleman’s obsessive search for new experiences both high and low, which is just the shadowy path that Dorian Gray goes down in Wilde’s 1890 novella, egged on by Wotton’s hypnotic proselytizing for a life lived purely for pleasure and sensation. Wilde’s mention of the earlier book in his own is a tribute from one controversial author to another. Both books disgusted Victorian moralists, of course, even though Dorian comes to a bad end. The means to this end is the Twilight Zone premise on which Wilde built his tale, which has made it probably the best-remembered piece of Victorian literature outside of Dickens: The young Dorian wishes that his portrait would age instead of him. (Transposed from a minor key into major, this could be a topsy-turvy Gilbert and Sullivan plot.) He retains his beauty; beauty is power; power corrupts; and Dorian’s sins, including cruelty, murder, and blackmail, show up reflected in his gradually uglifying painting. Disarming his critics, Wilde claimed that in Picture, rather than being immoral, “I think the moral too apparent”—namely that “all excess, as well as all renunciation, brings its own punishment … Is this an artistic error? I fear it is.”

This production’s sly, fold-upon-fold Montesquiou connection—echoing onstage a portrait of a man who was alluded to in a book described in a novel about a portrait that echoes a man—is just one of the ways Book-It, even in its simple staging, builds Wilde’s fictional world. Clad in white in Act 1 and black in Act 2, Chip Sherman’s Dorian moves chillingly from naivete and susceptibility to sociopathy, assuming command of the show, casting his spell over it, just as Dorian does his friends. One of these is the painter of the portrait, Basil, captivated and then crushed by Dorian; Jon Lutyens plays him affectingly, his consuming guilt the flip side of Dorian’s icy callousness. Guilt over what? The love that, if it dare not speak its name, comes pretty darn close. The source for Book-It’s script, by the way, is Wilde’s less equivocal first draft of Picture, before the magazine that published it de-gayed it (leaving enough hints, though, to make the book damning evidence at Wilde’s 1895 trials for “gross indecency”) and before Wilde later expanded it to novel length. My favorite among adapter Judd Parkin’s additions is having Dorian say “I am what I am,” a black-humored twist on the campy gay-pride anthem from La Cage aux Folles.

For those who know this final expanded version, Book-It’s staging leaves out Wilde’s spliced-in subplot in which the brother of a woman Dorian betrays seeks revenge. Anastasia Higham makes the most of her brief appearance as this woman, an actress Dorian momentarily falls for. I’ve long been fascinated by actors asked to portray bad actors—think Sarah Jessica Parker in Ed Wood—and Higham is amusingly excellent, then dreadful, in her two Shakespeare soliloquies. The chorus, delivering Wilde’s language richly and musically as well as playing miscellaneous small parts, are Ian Bond, Imogen Love, Michael Patten, and Jon Stutzman. And Simmons is genuinely superb as Wotton; exquisitely poised, effortlessly magnetic, and avoiding the cliches of mere foppishness, he’s the devil on Dorian’s shoulder, and even amid this splendid cast you can’t take your eyes off him.

The Picture of Dorian Gray

Thru July 1 (Wed–Sun) | Center Theater at the Armory, Seattle Center | $26 and up | book-it.org.