The Ferguson, Missouri, shooting death of Michael Brown and its ongoing national fallout provide a sadly auspicious moment in which to mount a play about Martin Luther King’s final hours in Memphis. Yet rather than preach, Katori Hall’s 2009 dramedy takes us down an imaginative rabbit hole behind the door of Room 306 at the Lorraine Motel on April 3, 1968. Burton Yuen’s whimsical pink curtains and bedspreads suggest fairy tale as much as newsreel in a play that seeks to uncover the regular man behind the icon—the stinky feet, smoker’s breath, and roving eye of the dreamer.

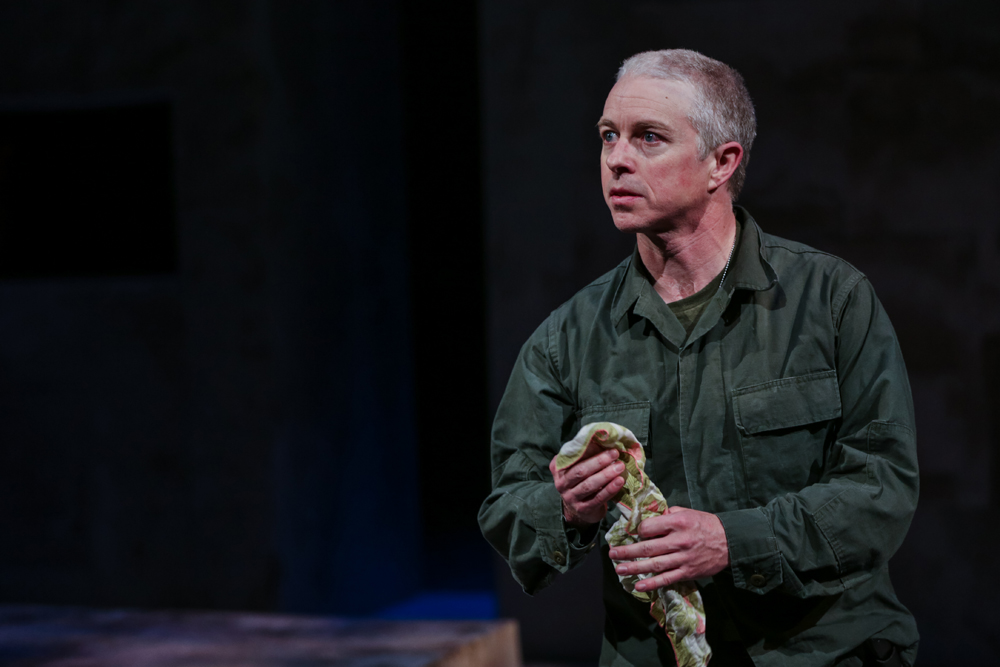

Reginald Andre Jackson brings a demeanor of intelligence, strength and road-weary fatigue to this MLK. Depleted as the battalion of dead paper coffee cups lying around the room, King sweeps in, beelining for the john whence we hear him pissing. “America is going to hell,” he intones. We hear the evidence: A 16-year-old black boy was killed by police the prior week during a protest King organized; the Vietnam War is a quagmire; and blacks are restricted in their comings and goings—even those of King’s stature.

But the revelation of both this play and this production is Camae, the earthy chambermaid who brings “Preacher King” his room-service coffee and recommended daily requirement of smart-mouth. Brianna Hill’s magical performance carries the uninterrupted 90-minute piece when the script’s devices wear thin (like King’s insatiable lust for cigarettes, which she reliably provides from her brassiere—King’s excuse to keep her in the room). Camae’s scrawny pluck endears, and Hill’s glorious upswept eyes channel pity, disgust, self-aggrandizement, affection, and mystery. Her comedic one-liners—like “Civil rights’ll kill you before those Pall Malls,” delivered in the non-code-switched Southern dialect she and King share in privacy—help distract King from his cares.

Director Valerie Curtis-Newton’s delicate touch lightens the inevitable telegraphing of a death foretold and neutralizes an irritating phone-call sequence that could ruin the play. (It’s a writer’s device of Hall’s that Hill helps save.) Toward the end of The Mountaintop, the set breaks apart like a future-filled egg, with display monitors folding resonant moments of history, lyric, and rhetoric into the motel story like stiff egg whites into lively batter. This marvelous mashup, an annunciation of sorts delivered by an uncanny messenger, readies the complex, conflicted human man for his final march. ArtsWest, 4711 California Ave. S.W., 938-0339, artswest.org. $15–$35. 7:30 p.m. Wed.–Sat., 3 p.m. Sun. Ends Oct. 5.

stage@seattleweekly.com