The age-old dilemma of whether to preserve sad history or plow right over it undergirds many of August Wilson’s plays, including this, the fourth of 10 in his touchstone “Pittsburgh Cycle.” The dilemma tugs like an undertow beneath the lore-rich three-hour saga precisely because both options are valid, commendable, imperative, and mutually exclusive. At the center of what escalates into a property war sits a blood- and tear-burnished family piano representing both the tortured past and the potentially promising future of an African-American clan in 1936. If you can’t simultaneously afford both future and past, which do you choose?

Berniece Charles (Erika LaVonn) wants to keep the past—including the piano—close. For her, the magnificent instrument—carved to depict her ancestors during slavery—is like a revered elder for whom multiple lives were sacrificed. For her brother Boy Willie (Stephen Tyrone Williams), eager to invest in land their family used to work as slaves and then sharecroppers, the piano represents a ticket to economic independence. On William Bloodgood’s drably respectable living-room set, the exquisitely rendered instrument shimmers with otherworldly power.

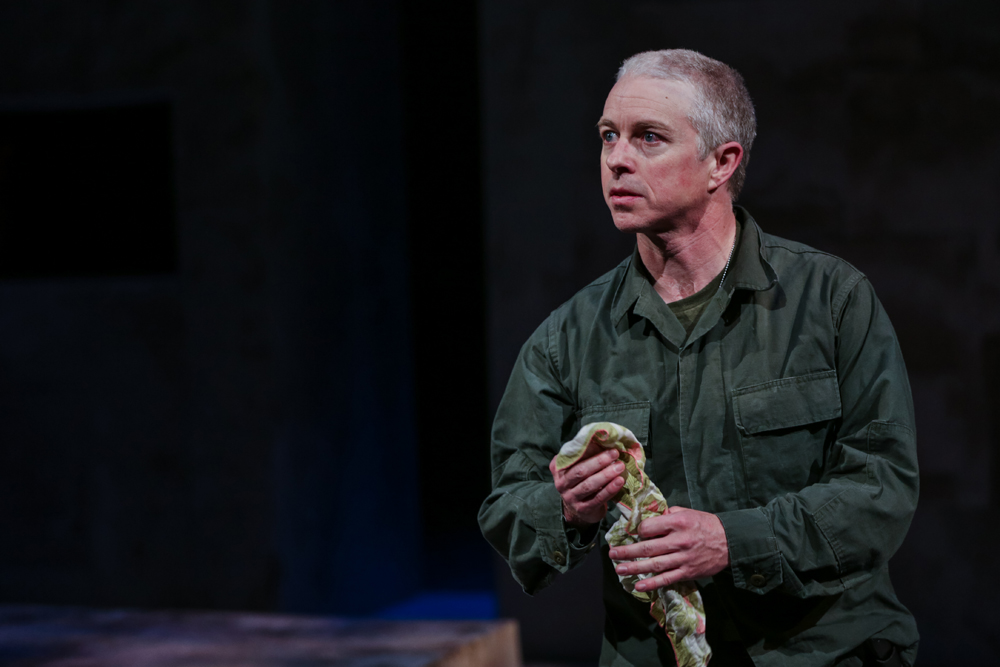

Berniece’s home churns like a busy tidepool. Uncles Doaker (Derrick Lee Weeden) and Wining Boy (G. Valmont Thomas) impeccably tell labyrinthine stories yet exemplify the career limitations for black men of the era. Willie’s friend Lymon (Yaegel T. Welch) pines and prostrates himself for women; preacher Avery (Ken Robinson) courts a stony Berniece; and good-time gal Grace (a very wiggly Allison Strickland) calls on Willie. Director Timothy Bond—formerly local, now with Syracuse Stage—orchestrates breezy informality, and some of the richest chords involve bursts of harmonized blues and pot-banging percussion by composer Michael G. Keck.

Still, as in real life, there are laggy times. Perhaps too heavily, Wilson’s 1990 Pulitzer winner relies on supernatural elements to shake things up and resolve the plot. There are ominous noises and electrical blackouts, plus offstage manifestations of a ghost—the white landowner, recently drowned in the well—at the top of the stairs. These occult tendencies can feel like a bit of a deus ex machina cop-out, given our emotional investment in Berniece and Willie, whose unresolved sibling conflict concludes with a didactic lesson from beyond. But it doesn’t ruin the pleasures of uniformly fine acting, a changed historical context since the last local staging in ’93, and the sense of enduring kinship. Audience and performers still steep in the glow of that tempestuous heirloom.

stage@seattleweekly.com

THE PIANO LESSON Seattle Repertory Theatre, 155 Mercer St. (Seattle Center), 443-2222, seattlerep.org. $17–$102. 7:30 Wed.–Sun. plus matinees. Ends Feb. 8.