Choreographer Donald Byrd has been working with thorny issues for most of his career. The history of race relations in America, the ongoing conflict between Israel and Palestine, the Holocaust—these and many other volatile topics have been part of the repertory he’s made in Seattle as the director of Spectrum Dance Theater. But as he unpacks these emotional subjects, he uses highly technical and abstract movement as the raw material for his choreography. Byrd has been mixing passion and structure for quite some time, and they are both part of Shot, his newest work for the company.

Shot is an examination of violence in America—specifically the unsettling number of police shootings with young black men as their targets. The program opens with a roll call of the deceased and a montage of cell-phone videos that catch some of their last moments. These are home movies of chaos, raw footage, and sound recordings, and their staticky nature adds to the general sense of dread and disorientation as we realize what we are seeing and hearing. While these recorded images, projected on the façade of what looks like a police station, are repeated sparingly during the rest of the work, the initial blitz, ending with a voice saying “This world is a mean world to live in” knocks us flat.

This opening sequence resonates as the cast assembles, and the next sections are indeed as sharp as a gunshot. In a series of small ensembles and solos, they establish the movement vocabulary for the work. Sharp and quick, isolated gestures pile atop each other with a sense of urgency. This is mostly abstract material, rather than mimetic or acting business, until they reach the end of their phrase and retreat with their hands up. This recognizable gesture stands out at the end of so much abstraction.

Text figures throughout Shot, both excerpts from the cell-phone videos and scripted commentary. As we begin to realize that the central video at the beginning of the show is of the September 2016 death of Keith Lamont Scott in Charleston, N.C., we listen to his wife’s chilling recording of that whole event. As she tries to mediate between her husband and the police, her chant, “He better live,” shifts from a demand to a prayer. Later in the work, several dancers sort themselves out behind two police barricades, shouting at each other, a verbal exchange that devolves from disagreement to virulent name-calling.

Byrd continues to use technically skilled performers and a high-intensity approach to his choreography—his dancers regularly whip off multiple turns and other kinesthetic challenges with an urgency that underlines whatever they’re doing. They approach both the narrative and the more abstract material with the same fervor.

Byrd himself appears in Shot as a kind of instructor or preacher, seeming to read from a prepared text about “the talk” that parents, particularly African-American parents, have with their children as they start to enter the world independent of their families. Through a long list of details, the central goal is always the same—to get home alive. Byrd’s no-nonsense delivery reinforces his introduction, that these are “rules for survival” and we had best pay attention to them. When he reappears later in the work to repeat some of them, he seems exasperated that we hadn’t internalized them long ago.

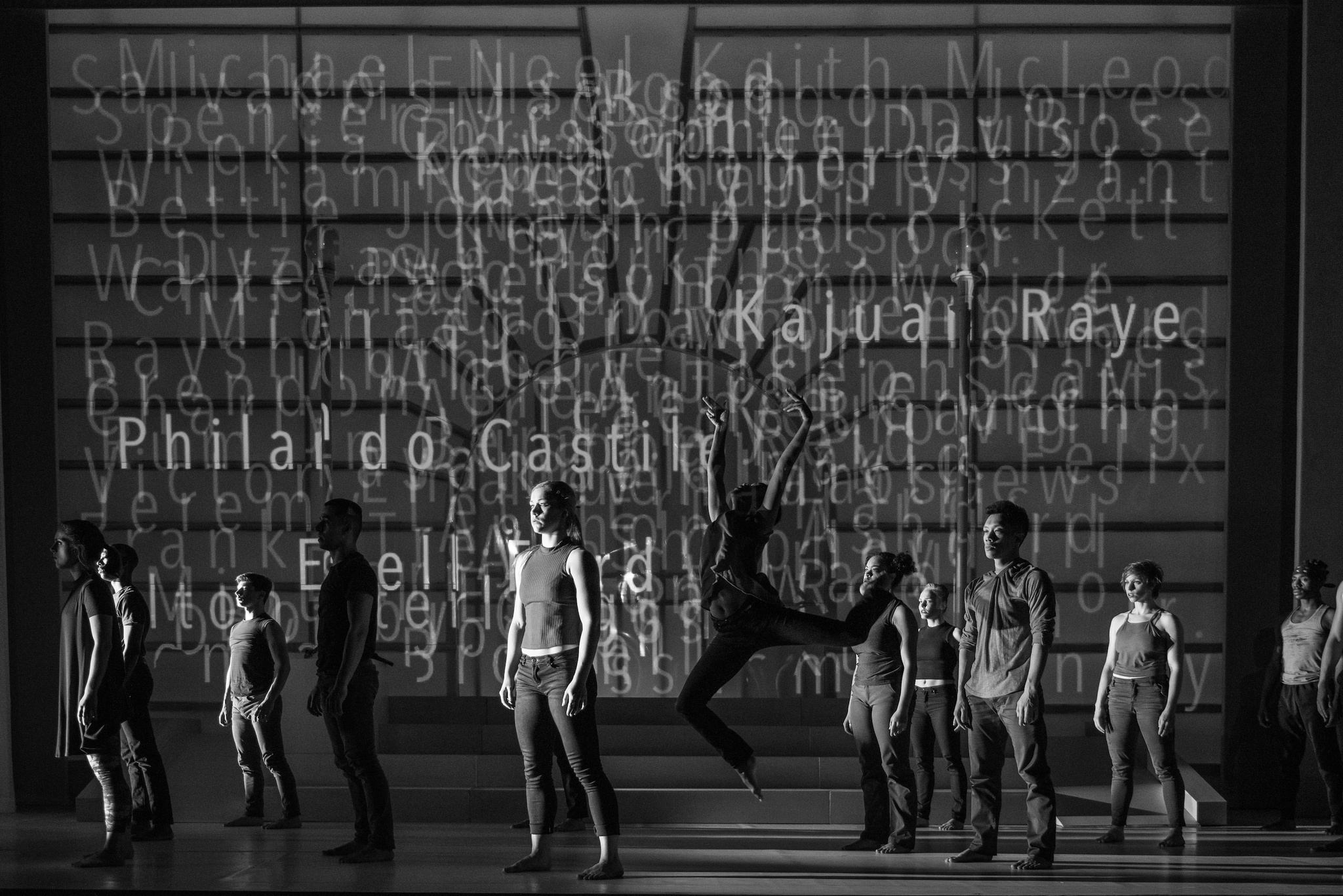

The opening roll call repeats toward the end, with names projected on the set and a fresh series of solos. In a post-show discussion, Byrd explains that the dancers were assigned individuals to research; while these solos aren’t dramatizations of those people, they are supposed to honor them in some fashion, and recognize that someone who was alive is now dead. The material starts elegiacally, but the accumulation of names intensifies the dancing and makes us a part of that memorial assignment. Eventually we return to the video of Keith Scott, this time with dancer Nia-Amina Minor speaking the text. The fact that we know what will happen does not make it any easier to hear the event unfold, nor should it. Spectrum Dance Theater, Leo K. Theater at Seattle Repertory Theater, 155 Mercer St., spectrumdance.org. $21–$42. Ends Sat., Feb. 4.

dance@seattleweekly.com