Dürer, Rembrandt, Hogarth, Goya, Picasso… R. Crumb. It’s an odd mix of artists from over five centuries to feature in one show, but Seattle Art Museum pulls it off in its latest exhibition, Graphic Masters. The works (over 400 pieces, half of which are by Crumb) can keep one busy for at least an afternoon—and I recommend that you not attend at peak visiting hours, as taking one’s time and getting close to the work is the only way to appreciate the details. The museum has a few magnifying glasses on hand in each gallery, but if you come on the weekend, you may want to bring your own.

For visitors not well-versed in printmaking methods (e.g., woodblocks, engraving, etching), SAM provides small, illustrated pamphlets on the subject, titled “Graphic Content”—one of the better decisions made in the exhibition planning, as it allows guests to refer to the guide as they examine the works instead of crowding around wall texts that might have detracted from them.

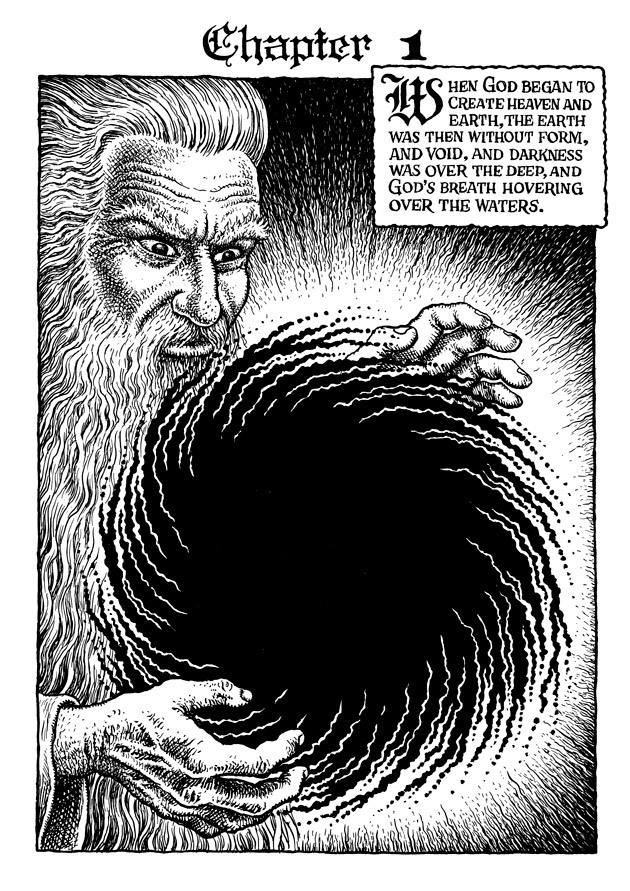

Graphic Masters is not a thorough survey of any one artist, nor is it an exhaustive look at the medium’s technical aspects. The artists are featured chronologically and bookended by Biblical themes: Dürer’s Large Passion and R. Crumb’s Book of Genesis. Excepting Rembrandt, there is a complete series of work from each artist. Moralizing is common among them. Goya and Hogarth are satiric, while Crumb’s Genesis presents the Abrahamic mythology (one translation of it, anyway) drenched in sweat and grime, closer to how the actual Bronze Age probably felt … but certainly influenced by Hollywood.

The limited number of works by Rembrandt (which were among the highlights of SAM’s 2013 Kenwood House exhibit) cover various myths, but are also quite intimate, much like Picasso’s Vollard Suite. This latter series doesn’t vary much in its content—replete with erotic scenes, minotaurs, and nymphs—but this specificity just deepens one’s appreciation for its archetypes and sensuality as one lingers from one piece to the next.

Goya, meanwhile, lingers on themes of deception, prostitution, and all manner of human folly in Los Caprichos, his series of 80 etchings and aquatints. Its second half is especially devoted to superstition, represented by witches, demons, and bestial priests. The didactic text next to plate 43, “El sueño de la razón produce monstruos” (“The sleep of reason produces monsters”), recognizes its particularly iconic status, but visitors will find dozens of dark gems in this series. They stun with both their technical mastery and their unflinching grotesquerie.

Though Goya was a court painter, he was not a partisan for royalty. His real loyalty was to humanism and the Enlightenment, and the very format of Los Caprichos can be seen to reflect that. In essence, Goya modernized the Emblemata book, a genre created by Alciati, the father of legal humanism in France. His picturesque emblems expressed ideals of justice and temperance, often through well-known myths and legends. It sparked a small craze for such works in Western Europe in the 16th and 17th centuries.

By the 18th and 19th centuries, the genre was a little quaint, but new techniques, pigments, and papers had expanded the possibilities of printmaking, allowing it to come into its own as an art form, not just a means of rapid reproduction. Goya used these new techniques to create more complicated tableaux, but went even further by shunning the sanitized myths and axiomatic wisdom common in old emblem books. Instead he drew from the contemporary world and metaphorical chimeras, and made the accompanying texts equally sinister and cryptic. Some are more overtly critical of institutions, including the Spanish Inquisition, and it was fear of reprisal by the Inquisition that led Goya to pull Los Caprichos from publication shortly after it was released.

Goya’s works are too ambiguous and dreamlike to simply be called political cartoons, but they were a sort of protest, certainly. Compare them with Hogarth’s series A Harlot’s Progress and A Rake’s Progress, which became popular satiric works when they were published in the early 1700s. Hogarth was clever, an exceptional engraver, and much more the cartoonist. These print series were based on paintings by Hogarth, narrating the downfall of two individuals degraded by greed, lust, and booze. In the 18th century, when Hogarth and Goya were active, growing density in cities was breeding larger networks of corruption and a class of arrivistes.

The iconoclastic Goya left his critiques more open-ended, while Hogarth was very much part of the establishment and interested in reforming viewers. There is a more direct link between Hogarth’s work and works like Dürer’s Passion. Instead of dogma, Hogarth conveys lessons in ethics, temperance, and social norms; instead of saints, he goes for savage caricatures. Their common ground, however, is the use of sequential imagery to tell a story in which each scene can be understood independently and as part of the full sequence. For this, Hogarth is recognized as a major influence on the genre of sequential art as a whole.

The way the exhibit begins with Dürer and and ends with Crumb takes on new meaning in this light. Crumb at first seems an outlier in that he’s drawing, not etching or engraving, and the reproductions are made by modern printing processes. Using only black ink and Wite-Out, his tonal ranges and shading are limited, much like Dürer’s use of woodblock printing. The museum space unfortunately demands a linear layout, but the show is not linear in its curation; you can find all sorts of formal and thematic connections between the artists. The contributions from the curatorial team admirably resist imposing a single reading on viewers. The team is also to be commended for creating a digital catalog that can be brought into the exhibits by visitors in wheelchairs, who could not otherwise see some of the works, which are in a few spots hung a bit high, simply for lack of room.

After completely nerding out at The Getty Center’s Noir exhibit earlier this spring, Graphic Masters was a great way to experience a print show. Noir focused on the technical advancements that shaped printmaking in the 18th and 19th centuries, and included some of Los Caprichos; this exhibit’s focus is more plainly on the artworks themselves. Showing complete works by these six artists illuminates the intellectual advancements and skills that made a means of fast reproduction into a regarded art form—objects of charm, satire, and protest, indicative of their times but still stirring to this day. Graphic Masters, 1300 First Ave., seattleartmuseum.com. $12.95-$19.95. 10 a.m.-5 p.m. Mon., Wed., Fri.-Sun.; 10 a.m.-9 p.m. Thurs. Ends Aug. 28