In our shared mythology, the mother is the saint of selflessness. The mother was born to mother, whose aspiration to nurture is ceaseless like a rushing torrent. The mother may have labor pains, but the mother’s love is not work, since in our shared mythology, love is positioned as the inverse of work. For the mother, the enactment of love is its own payoff.

The mother is also the saint of devalued caretaking work. The longstanding degradation of women’s work and the separation of domestic work from cultural and economic contribution has sparked the scholarship and activism of many. Notably dubbed “the mother of materialist feminism,” Silvia Federici argues that Marxist critique seldom accounts for how the sexual division of labor and unpaid housework played a key role in the process of capitalist accumulation. Further, the romantic idea of effortless feminine care has been brandished to exploit the labor of mothers and occupational mother figures.

For her curatorial debut at The Alice Gallery, artist Satpreet Kahlon asked seven artists to choose a piece of handmade craft by a mother in their family, then create a new piece of fiber work in response. The result is the remarkably intimate exhibition from which we rise. Nicole Barakat responds to her grandmother’s crochet piece, replicating the stitch patterns with her own hair. In another piece, Markel Uriu sculpts a vestment like ones her grandmother wore as a minister. “I wanted to showcase the labor of maintenance,” Uriu explains. “Boro fabrics were articles of clothing that were repatched as they wore out, resulting in intergenerational patchworked pieces of clothing and textiles.” Her vestment hangs in the gallery next to the wooden bird her grandmother chiseled while in a Japanese internment camp.

The show’s intimacy is expressed both in subject matter and use of materials. That the handicraft piecesseem stark against the gallery’s white walls speak to craft’s historical relegation to the bottom of the hierarchy of art. An extension of women’s exclusion from cultural and economic spheres, decorative handicrafts have been long deemed everyday, utilitarian objects, and therefore trivial, non-conceptual, and certainly not art objects.

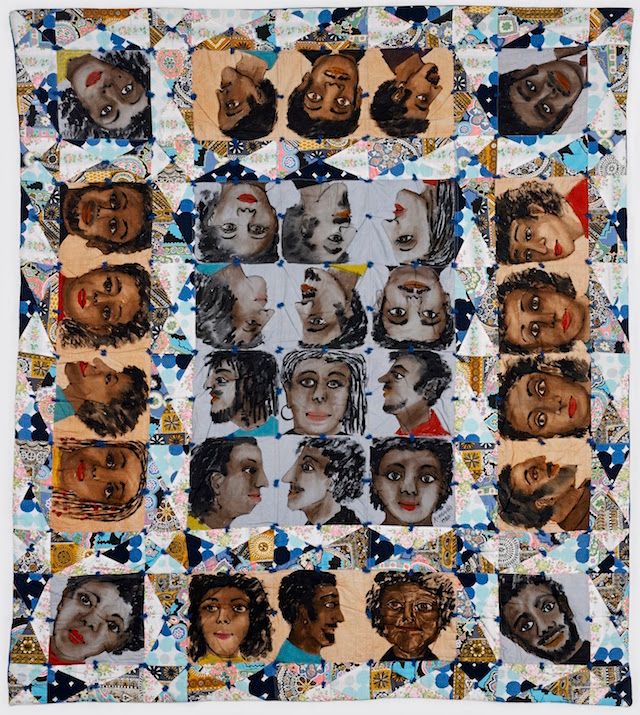

In the ’70s, some feminist artists gained attention for the concerted elevation of household craft techniques, arguing that this feminized domestic work upholds familial bonds, thereby measurably sustaining the wage-labor workforce. I think particularly of Faith Ringgold, who incorporated her family as subjects and collaborators in quilt pieces such as Echoes of Harlem and oil paintings like For the Woman’s House. Ringgold has stated her motives: to honor the women in her life whose uncredited work made possible her career in the arts, as well as uphold her family’s tradition of creative collaboration. As Ringgold does, from which we rise recognizes familial forebears long unacknowledged.

Faith Ringgold’s “Echoes of Harlem.” 1980.

The curator’s own mother, Kulwinder Kahlon, made work responding to her mother, Manjit Kaur. Satpreet tells me that for her grandmother, particularly during the period of tumultuous change in Pakistan during the Partition of India, embroidery work was about retaining a feeling of sophistication in the family. Kulwinder stitched patches from memory—one for every different stitch she learned from her mother. Exhibitions at The Alice Gallery often feature a writer in residence, and this show’s writer, afrose fatima ahmed, created on-the-spot poems in response to each pair of works. Beside Kulwinder’s patches is a poem called pigment: “my inheritance was a palette/laid with hues so vibrant.”

Hand-threaded pillowcases, wrapped dupattas: These are the ancestral breadcrumbs along the travel paths of migration, tracing the distance between countries and generations. They can navigate the way home. The preservation of memory and inherited knowledge among women through craft has not only tethered families and communities, but has served as a clandestine act of resistance against patriarchal isolation. The coordinated act of trading knowledge and techniques as feminist strategy is evocative of Shulamith Firestone’s “consciousness-raising groups” or Angela Davis’ “black counterpublic.” Kahlon calls it a “non-Eurocentric intergenerational exchange … tracing family lineage and cultural survival through textiles.”

How timely that this show opened the weekend of Mother’s Day, a holiday of such intensified appraisal for mothers it’s like a day of repentance for their sacrifice. May from which we rise remind us to honor mother figures through a materialist, feminist lens by acknowledging their love relations as labor relations. To echo the sentiment of Alice Walker’s essential 1974 essay “In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens,” may we question who gets to be remembered as artists, and regard the women whose creative sparks didn’t result in a florid painting but in actions that kept the family warm, the home adorned, and the garden vivid with flowers.

from which we rise, The Alice, 6007 12th Ave. S., thealicegallery.com. Free.Noon–7 p.m. Sat. or by appointment. Ends June 19. visualarts@seattleweekly.com