What earthly climate besides the sea is as brutal as it is serene? Looping waves may offer narcotic solace, but the water’s vastness and its threat to engulf all with an arrival of furious tides brings less comfort. To the sea you are nothing, which is both soothing and terrifying. As Emerson expressed in poem, “It will destroy/in perfect time and measure/with a face of golden pleasure/elegantly destroy.”

Like outer space, the ocean glistens with a cold inhospitality for the human body, a quality that terrifies some while motivating others to infiltrate and regulate it for exploration. Tank Hypnosis, Dakota Gearhart’s exhibition at Glassbox Gallery, dives into our complicated relationship with bodies of water both as a salve and as an umbrous void of disorientation.

Gearhart is fascinated by the seductive hypnotherapy of water. The former marine-biology student-turned-artist has been studying the way tanks (aquariums, scuba tanks, and sensory-deprivation pods) allow us to enjoy what marine biologist Wallace Nichols calls a “blue mind,” a meditative state of water-induced calm. The exhibition features four explosive multimedia sculptures that Gearhart built from a charged assortment of found materials such as wood, steel, and Styrofoam, fused with monitors of digital video projection and tanks of live feeder fish. Like these videos, digital photographs contain footage Gearhart found online as well as recordings from her trips scuba-diving.

“I’m interested in how we take the healing properties of water and put it in boxes,” Gearhart tells me. People’s interactions with water have always reflected their era’s attitudes toward wellness; from Chinese to indigenous American medicinal practices, water is a key element for balance and restoration. In the mid-18th century, physicians prescribed seawater as a remedy for ailments from body soreness to “general melancholy,” as if it were ibuprofen. They also recommended chugging glasses of seawater mixed with honey or milk. And the Romantics, true to brand, asserted that swimming could increase sexual vitality.

In small portions, the sea may be curative, but it induces the opposite effect when you confront its immensity. Gearhart observes that “the scariest thing about being underwater is that the grid disappears, and that there’s no way to position your body in the right direction.” While a loss of control seems antithetical to a state of calm, Gearhart draws a connection between the two: “I’m interested in organic psychedelic experiences, altering your way of seeing through everyday acts. How can the loss of orientation be used to shape psychic space?”

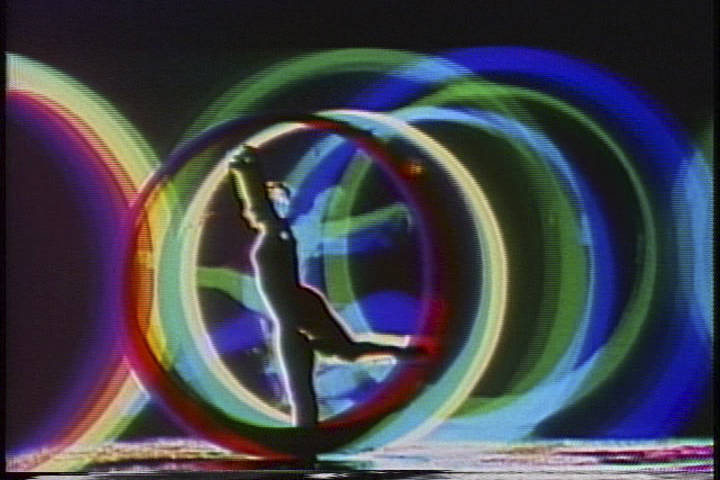

The work in Tank Hypnosis is certainly disorienting. The sculptures are hard to describe, and it feels moot to enclose categories around pieces so joyously language-defying. Screens flash bright aquatic footage in bursts along with inscrutable sounds of splashes and gurgles. An unidentifiable tar-like substance coats pillars that support entanglements of monitors and wires. The scuba-diving footage, glitched out with Adobe Premier and Aftereffects, isn’t loyal to any narrative structure. Live feeder fish swim back and forth indifferently among the work—fish which, for those concerned, are being closely cared for by Gearhart and Glassbox Gallery’s staff for the duration of the show.

“Buoyancy Screen” by Dakota Gearhart. Steel, Wood, Cement, Styrofoam, Paint, Plaster, Monitor, HD Video, Aquarium, Filter, Mirror, Wire, Comet Goldfish, Tar.

Perplexing to me is the choice Gearhart makes to position technology as a prominent feature in her work, as opposed to similar art that celebrates nature but often obscures the technology that makes our interactions with it possible. She’s concerned about how many innovations, such as scuba-diving, have been advanced by the military, whose interactions with the sea have less to do with healing and more with classification, acquisition of resources, and geopolitical warfare. Could this be why the show’s apparatus, mutations of oiled blotches and exposed wires, look so ominous? It certainly hints at the ethical questions and detriment of human interaction with the sea—and knowing Gearhart’s uncertainty about the subjects, I found myself wanting more of this commentary in the work.

Looking at Gearhart’s creations, I ran them through the inventory of my associations to place what I saw in the right mental compartments. When I couldn’t, my brain turned on its high beams, alert with attentiveness and wonder. In familiar environments, our senses adapt and coast, and sensory receptors develop a diminished sensitivity to environmental stimulus. Gearhart wants to interrupt sensory adaptation to “see what happens when you lift the veil.” Lifting the veil, or expanding your consciousness, often gets misconstrued as an endorsement of psychedelic drugs, which isn’t what Gearhart means here. She’s interested in more ordinary ways to see differently, like traveling to a new city or looking at a piece of confusing art. These little acts of disorientation can be rousing, like splashing cold water on your face.

Tank Hypnosis, Glassbox Gallery, 831 Seattle Blvd. S., glassboxgallery.com. Free. Noon–5 p.m. Tues.–Sun. Ends June 3. Artist talk 7 p.m. Tues., May 23.

visualarts@seattleweekly.com