Construction anxiety may rival weather as Seattle’s top conversational opener. Look anywhere and you see it: skeletal steel frameworks of towering soon-to-be skyrises that already cast shadows on the sidewalks. Billowing plastic tarps over buildings destined for demolition like corpses at a morgue. In the dim terror of construction booms and their by-products of gentrification, displacement, and diminished public space, the eeriness lies in the imperceptibility of these particular villains. Who and what are behind all this? What are their stated motives, and do their actions reveal anything different? Caché, an exhibition at Gallery4Culture, extracts the conventions of the horror genre to differently articulate this real-estate nightmare.

Caché is a dark spoof of an urban-development firm that specializes in manufacturing townhomes. The exhibition includes a showroom of architectural models, a commercial home tour video, and a “process” table that displays absurd diagrams, blueprints, and sample swatches. The debut collaboration of Max Cleary, Jackson Baker Ryan, and Alex Boeschenstein, Caché was conceptualized from conversations among friends of varying proximities to the urban-development industry: Cleary and Boeschenstein worked together for a real-estate videography company, and Ryan has a background in architecture. All felt a general sense of unease about the proliferation of townhomes, which are peddled as a fast solution to solving density in the face of rapid population growth. “These skinny-talls are going up everywhere, looking hyper-designy,” Cleary says. “We wanted to look at townhomes as visual harbingers of the near future.”

According to the artists, the pronunciation of Caché is flexible. The accent is a reference to the arbitrary signifiers companies use to make generic products sound upscale. “We wanted to mimic how they’re branding ready-made houses with superficial images of luxury,” Cleary says. “It’s also supposed to be a fancier way of saying ‘cash money.’ ” The word cache also means a hiding place; and withdrawal from public life is indeed a legitimate fear around new housing developments, the fear that people will move into the city temporarily with no interest in investing in it as a shared-resource system. Read this way, Caché plays out the paranoia that social alienation and obsolescence are packaged as luxurious living arrangements.

“We talked a lot about the horror genre’s conventions, and how artists like Kubrick, Dario Argento, and even Orwell have utilized them to raise interesting political and philosophical questions,” Boeschenstein says. Since its dawn, horror has been a testing lab for societal anxiety: Think 1956’s Invasion of the Body Snatchers as a reflection of post-WWII worries of unparalleled development in nuclear technology, foreign intrusion, and brain manipulation. The artists of Caché were particularly drawn to the horror trope of the haunted house, which Boeschenstein characterizes as “a physical space as a holding-cell for memory, with a nefarious past trauma that shines into the present.” He says The Shining was a big source of inspiration: “[The movie] brilliantly weaves an allegory about America’s inability to reckon with its history of rationalizing violence through the principles of economic growth. It’s a political movie about how history can be an inescapable nightmare with spatial and physical dimensions.”

In Caché, the artists present a haunted house that inverts its mainstream mythos: a house that is haunted not from too much history, but from its void of history. Here is the haunted house as a brand-new, clinically sterile, squint-inducingly white townhome. “The townhome has a foreboding quality derived from its hereditary amnesia,” Ryan says. Boeschenstein adds that, “instead of [the home in The Shining], where the past shines toward into the present, the future might be shining backward, and the future that these townhomes insinuate is especially depersonalized and ahistorical.”

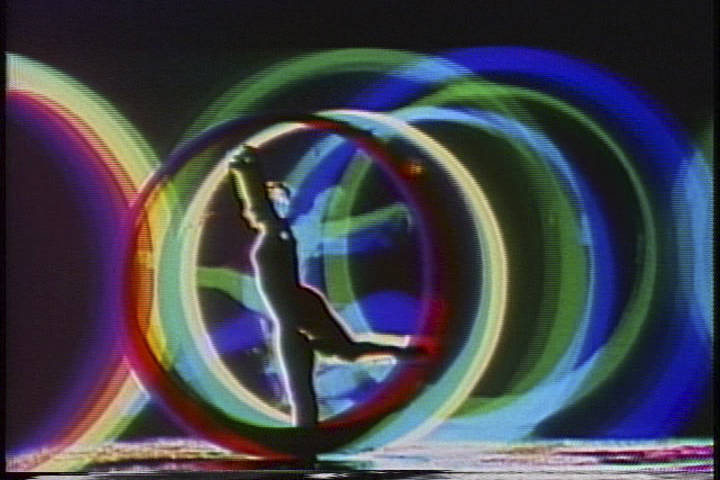

“Home Tour,” Caché, video still. Max Cleary, Alex Boeschenstein, and Jackson Baker Ryan

This sense of antiseptic horror is best encapsulated in the video piece. It begins as a real-estate commercial in which a character (played by dancer Coleman Pester) moves throughout an actual townhome that the artists rented on Airbnb. Save for a few IKEA-esque items like fake tea-light candles and plastic plants, the interiors are barren and the lights are stark, reminiscent of the ways photographers shoot tiny spaces to make them feel palatial. There’s a palpable tension between the character and the house, wherein the character attempts, as Cleary says, “to activate a space that refuses activation.” Throughout the film, the character is languid, intermittently lying face-down on the bed in the fetal position, as if zapped of energy from a force between the walls.

The visual cues in the video prod at the minimalist aesthetic that has swept design over the past decades, enabled by lifestyle magazines such as Apartmento, Kinfolk, and Dwell. When adopted by the real-estate industry, this aesthetic is a strategy in reproducibility, about achieving the largest amount of potential consumers by appealing to the lowest common denominator of tastes. The outcome is what writer Kyle Chayka has named “AirSpace,” a look that is everywhere yet belongs nowhere in particular.

There’s nothing inherently evil about preferring a pared-down environment, but it is interesting to consider minimalist home aesthetics as a recent offspring of urban planning’s adventures in multiplicity. Consider the legacy of William Levitt, “pioneer of the suburbs,” who spearheaded the mass production of more than 17,000 cheap, uniform houses, approaching them like any other product created on an assembly line. These homes unfolded spatial relationships: Their isolation, for one, meant that people needed cars to get around, which in turn transformed the way pedestrians could move on suburban roads. Likewise, Caché is fixated by this idea of sameness, and relates it to the horror trope of doubling, often expressed through twins. “Twins are portrayed as having telepathy with each other, and could be planning something right in front of you without you knowing,” Cleary explains. “The townhomes pop up in groups, possessing a twinship,” Boeschenstein continues. Like the Levitt homes, how would the multiplicity of townhomes change the way people are able to navigate the built environment?

Architectural theorist Keller Easterling insists that while the built environment is typically regarded as a collection of objects, it should be considered as the dynamic among active forms. She argues that infrastructural space, comprising repeatable formulas like suburbs, highways, and townhomes, shape the city and the lives of its inhabitants by releasing well-rehearsed chains of events that can escape detection. Caché’s enactment of the townhouse as horror villain allows us to consider how the seemingly natural yet intentional uniformity of these small, stark living quarters encroaches on our values of home, belonging, community, and diverse cultural ecosystems. If we can dissect the behavior and motives of the villain, we are more likely to figure out the escape routes.

Caché, Gallery4Culture, 101 Prefontaine Pl. S., galleries.4culture.org. Free. 8:30 a.m.–5 p.m. Mon.–Fri. Ends Thurs., April 27. visualarts@seattleweekly.com