As he slowed down on Highway 4 through a desert village called Takta Pol and stopped at the Afghan militia guard post in his battered Toyota Corolla, Salim Hamdan was about to discover what a truly long and winding road he was taking that day, November 24, 2001. It would lead to his sudden disappearance, withering secret interrogations, and the belief that he’d never again see his family, including a daughter about to be born. Ultimately faced with dying behind a barbed-wire prison fence without being charged with a crime, he’d find himself confronting the president of the United States in a landmark legal battle, waged in part by Seattle attorneys, which continues to this day. The epic detour would ultimately spawn global headlines and entice George Clooney to option the saga for the big screen.

But first Hamdan would have to survive the roadway checkpoint. It was manned by non-uniformed members of the Northern Alliance, a homegrown militia opposed to the Taliban and al-Qaida and backed by U.S. forces, who’d invaded Afghanistan on October 7. With a thick black mustache and a cherubic face, then-32-year-old Hamdan had driven taxis part-time in his homeland of Yemen and had become a chauffeur in Afghanistan. He was alone, without his usual passenger that day: Osama bin Laden had gone into hiding shortly after taking credit for launching the September 11 attacks on America.

As bin Laden’s driver since 1997, Hamdan had served as both chauffeur and bodyguard for the wealthy al-Qaida backer. He was paid $200 a month, a princely sum for an otherwise poor man with a grade-school education. The money was 10 times what he could hope to earn in Yemen, where poverty is endemic. He had ended up at bin Laden’s compound seeking work after being recruited in Yemen for jihad in Tajikistan. His Muslim contingent spent the better part of 1996 in Afghanistan, hoping to join comrades in waging holy war against Tajikistan’s pro-Russian government, but was turned back at the border. Initially, Hamdan drove a truck that carried bin Laden’s farmworkers to the fields around Kandahar. He moved up to become the terrorist leader’s driver, and, after 9/11, ferried bin Laden and his son around the region for several days as part of a motorcade of al-Qaida leaders. They stayed in safe houses or camped in the desert where, Hamdan would later insist, he learned for the first time that bin Laden was behind the 9/11 attacks.

The world’s most-wanted man had since fled southeast Afghanistan when Hamdan arrived at the checkpoint. Had bin Laden been in the backseat that Saturday on the dirt roadway outside Takta Pol, not far from the crossing to Pakistan, world history would have changed considerably. The freewheeling militia was quick to take prisoners or kill those who resisted. In front of the Toyota, according to later recollections by Hamdan and U.S. military personnel who arrived late on the scene, the Afghan soldiers scuffled with the driver of another Toyota, dragging him from his car and then killing him, dumping his body beside the road. In the line behind Hamdan, two men in a van resisted, and were shot to death by the soldiers.

The militia took a third man from the van into custody. A frightened Hamdan bolted from his car and began to run. Around him was a vast, flat landscape; he could jog for miles and still be seen. The soldiers watched him flee, and began to laugh. They soon went to a ditch where Hamdan, scared and sobbing, was hiding, and brought him back.

U.S. soldiers, responding to the gunfire, rushed from their nearby outpost. Army Maj. Hank Smith—whose group had days earlier been dropped by helicopter into the Kandahar region, the Taliban’s stronghold—took custody of Hamdan, agreeing to a $5,000 bounty. Smith would later say he was almost certain the Afghans would have killed Hamdan. His Toyota had arrived from the direction of the Pakistani border, and when the Afghans opened the car’s trunk, they found two SA-7 ground-to-air missiles in their carrying tubes. In the hands of al-Qaida or the Taliban, they could have been launched to bring down a U.S. helicopter. The major suspected he had custody of a genuine enemy combatant.

Smith did not know who normally rode in the driver’s backseat. But Hamdan, who speaks no English, would tell them it was bin Laden. In fact, despite harsh treatment and secret imprisonment, Hamdan would prove cooperative and truthful, U.S. officials would later admit. They believed what Hamdan said—except when he denied being a terrorist.

Watch: The interrogation of Salim Hamdan

At his March 13, 2002 afternoon press conference in the White House’s James Brady Briefing Room, President George W. Bush pointed out that “Terror is bigger than one person,” bigger, at least, than Osama bin Laden. “He’s a person who’s now been marginalized . . . I truly am not that concerned about him.” Anyone who thinks the war in Afghanistan focuses on one person doesn’t understand the scope of the mission, the president explained.

It was, in retrospect, Bush’s first “Mission Accomplished” faux pas. The supposedly marginalized financier of 9/11 would continue to lead al-Qaida long after Bush left office, defying a decade-long manhunt, until killed by Navy SEAL Team 6 at his Pakistan safe house on May 2, 2011.

While Bush claimed not to be interested in bin Laden, he was clearly determined to nail his chauffeur. Salim Hamdan was one of the first prisoners to arrive at the hastily created Guantanamo Bay detention camp in Cuba in 2002, and his case would become the first American war-crimes trial to be heard since World War II.

Though it would be delayed for six years, prosecutors had built up exaggerated charges against Hamdan, his defense team felt. Jurors would seem to agree. As one anonymously told The Wall Street Journal later, “Salim Hamdan was working for a bad organization and he knew that,” but he was no mad bomber. Jurors saw him as “like other young people who get mixed up in criminal organizations because they are ignorant or lack other opportunities.”

The government would draw a dark picture of Hamdan, noting his alias was “The Hawk,” and said bin Laden had held a wedding party for him. He had driven the terrorist chief to news conferences and speeches, and sometimes carried a machine gun—though apparently he never fired it. Still, there was little persuasive evidence that his duties amounted to much more than driving bin Laden and helping run the car pool. As The New York Times put it, “Mr. Hamdan’s offenses are not enumerated anywhere, but appear to include checking the oil and the tire pressure.”

The defense would discover from other detainees that Hamdan was indeed a low-level wheelman. Among those who agreed to give statements was no less than 9/11 architect Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, who suggested Hamdan was a mere uneducated grease monkey. The record would also show that Hamdan had cooperated with his captors and provided much-needed intelligence on al-Qaida (and on the hunt for his former backseat passenger), despite being shackled, hooded, and held in an undisclosed location for more than a month before being taken to a lockup in Kandahar. There, his interrogators would include everyone from the CIA and FBI to the Port of Seattle Police, who were helping to probe the case of “Millennium Bomber” Ahmed Ressam, arrested at the Blaine border crossing in 1999 en route to set off a bomb at LAX.

A video would also show Hamdan, during a 50-minute interrogation, sitting on the floor of a hut, hands bound, freely answering an interrogator’s questions. In the footage, he admits to have worked for a charity thought to support al-Qaida, but denies he worked for terrorists. Asked whether he’s being honest, Hamdan replies, “Why should I lie? I am a detainee. I am your prisoner now . . . It is all over.”

That Hamdan eventually would get his day in court was itself a victory. The Bush White House, with Vice President Dick Cheney as point man, had unilaterally decided to set up its own kind of justice system at Gitmo—its primary feature being a lack of justice. Prisoners could be held without charge, interrogated (and tortured) without legal representation, and never be given constitutional rights against self-incrimination. Should charges actually be filed someday, their fates would rest with a military commission that would essentially make up the rules as it went along.

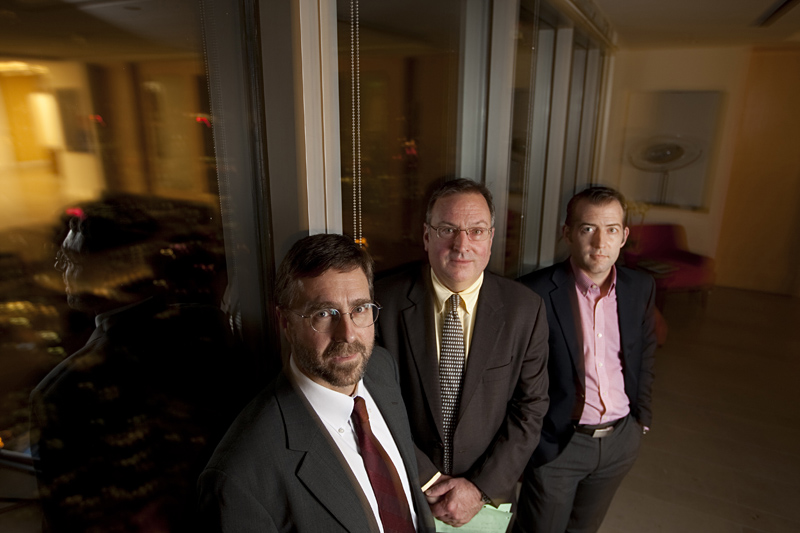

President Bush’s success at implementing what his critics called a kangaroo court would come to ride solely on the Hamdan case, thanks to a defense team that included four lawyers from Seattle and a military attorney and Seattle University law grad named Charles Swift. “I’m not opposed to war-crimes trials,” says Swift, a Washington, D.C.-born Naval Academy graduate who resembles actor Ryan O’Neal. “But the rules in this instance were inappropriate.” Now a criminal defense attorney in Seattle, Swift, 51, was a Navy Judge Advocate General (JAG) officer in D.C. when he was appointed in 2003 to defend Hamdan against terrorism charges.

“Military commissions were courts of necessity, held on the battlefield, for instance, when there was no way to get to a courtroom,” Swift says. “But that wasn’t the case with Hamdan or the others at Gitmo. There’s an available military court system and the federal courts, where we’ve been trying accused terrorists for years. What the White House wanted to do was use a military commission to get out from under the law. The president looked at it and said, ‘This is an extraordinary situation, and allows me to make up the rules as I see fit.’ “

Swift’s marching orders from the Pentagon were to represent Hamdan by convincing him to plead guilty, Swift says. The detention camps at Gitmo would eventually process almost 800 suspects over the next decade, most of them subsequently released without charges, but having suffered from their treatment. (Assorted inspections over the years have found evidence of Gitmo captors using humiliating acts, forced positions, extreme temperature changes, and squalid solitary confinement to abuse prisoners.) That didn’t seem to matter much to the American public, at least in the immediate wake of 9/11. Gitmo, after all, was the home of some certifiably bad guys. What was not to like when, say, Mohammed al-Qahtani, the would-be 20th hijacker, was forced to wear a bra, or Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the proud admitted mastermind of 9/11, got his balls squeezed by a female interrogator?

It was in that vein that Swift was told to show up at Gitmo in his Navy uniform and tell bin Laden’s driver that if he took a plea bargain, he’d get out in 20 years. But he’d also have to testifiy against other detainees. His client told him—as he had insisted to interrogators—that he was never a member of al-Qaida nor fought on their behalf. Instead of persuading Hamdan to take the deal, Swift talked him out of it. “He wasn’t guilty of what they wanted to charge him with,” says Swift.

But if he was going to buck the system, Swift needed help. He turned to Georgetown Law professor Neal Katyal. An expert on federal and international law, Katyal served as Al Gore’s co-counsel in Bush v. Gore in 2000, and would later be appointed Acting U.S. Solicitor General by Barack Obama. They had to get the issue before the federal court, and came up with the unlikely proposition of Osama bin Laden’s driver suing President Bush.

“The administration, from the onset, sought to defend Gitmo, sought to defend the commission, not on the idea their actions were right and legal, but on the idea the [federal] courts couldn’t interfere,” says Swift. “That was clearly a question for the courts to take on.”

Swift and Katyal decided to file the suit in the liberal-leaning 9th District circuit court, based in San Francisco and with a jurisdiction which encompasses Seattle. The D.C. circuit, they felt, would likely dismiss such a suit outright. Fortunately, Swift still had standing in Washington state. He served in the Navy in Bremerton, then attended Seattle University School of Law in the 1990s. By claiming Washington as his last place of civilian residency before rejoining the Navy to become a JAG officer, he was eligible to file a lawsuit here in his name, on behalf of Hamdan, in federal court.

Katyal connected with an acquaintance who worked at Perkins Coie, the 100-year-old Seattle law firm, and put in a call for help. “They’d be great,” a skeptical Swift said of Perkins, “but I really doubt we can get them.” Corporations were their specialty, from startups to Fortune 500 companies. But the timing was fortuitous. Harry H. Schneider Jr., an easygoing 58-year-old veteran intellectual-property litigator at Perkins (which employs 850 lawyers in 19 offices across the United States and Asia), had just given a speech at an event honoring one of his partners for having devoted exceptional time to pro bono work. When he returned to the office the next day, in March 2004, Schneider felt motivated, realizing he hadn’t done free legal work in two decades.

He went to the pro bono coordinator. “Find me a case,” he said. “Any old case.”

Two weeks later, Schneider was handed a note. Call these guys in D.C., it read. They have a pro bono case.

So Schneider called Swift. “Our client’s at Gitmo,” the latter explained. “Drove for bin Laden. We want to sue George Bush. Like tomorrow.”

Schneider was intrigued. “Here was this fellow, Swift, a military officer, who had received orders to defend a prisoner accused of being an enemy of the United States, and to do so while his fellow officers and enlisted personnel were in active combat in other parts of the world against the same enemy,” he explains. “My thinking was that was an awesome responsibility.”

Schneider walked out of his office in Perkins’ skyscraper headquarters on Third Avenue and down the hall to fellow attorney Joseph McMillan, whom Schneider knew had been following the goings-on at Gitmo. “Joe’s reaction,” said Schneider, “was ‘Harry, you’ve got to take that case, and second, you’ve got to let me work on it.’ “

Schneider wasn’t yet convinced, however. He stalled Swift and Katyal by telling them “I have to run a conflicts check,” a routine review to see if, for any reason, the case conflicts with those of his other clients. “Neal [Katyal] still finds this hilarious,” Schneider says. “But I needed to think about what we were being asked to do, and I needed to buy some time to think it through.”

McMillan and Schneider were, it seems, the last people Hamdan might have picked to have in his corner. Both represent well-heeled clients on issues such as breach of contract, patents, and securities disputes. Boeing, the nation’s #2 defense contractor, was among Schneider’s heavyweight clients. “Neither I nor Joe had done any criminal-defense work before,” he says. “We’re commercial-litigation lawyers. We represent companies.”

But so far, this was just a civil action. Schneider and McMillan could help devise strategy and write briefs, and their firm’s deep pockets would be pivotal. “I jumped at it because it was a case all about due process, civilian rule, and equal justice under law,” says McMillan, a trim, lightly bearded 52-year-old litigator and onetime Peace Corps volunteer. “It doesn’t matter what kind of law you do. Those are the principles that I learned from the time I was a boy to the time I graduated from law school.”

Schneider remembers that when he told Bob Giles, Perkins’ managing partner, that he was planning to take on the case, Giles’ first response was “You’re kidding!” Giles confirms that. “At that time, the 9/11 attacks were very much on our minds,” Giles says today, “and representing anyone associated with bin Laden triggered a knee-jerk reaction that was not positive—at least until Harry gave me more details and we focused on the legal principles involved.”

The firm waded in, with fellow Perkins litigators Charles Sipos and David East also playing important roles. No one anticipated it, but the firm would end up donating the equivalent of “several million dollars” in legal fees over the next eight years, Giles says, and “several hundred thousand” in out-of-pocket costs.

“Perkins was in with us because they didn’t care what the trial would say about them. It was about principles,” says Swift, who still specializes in military law as a partner at Swift & McDonald in Seattle. “They came in without having even met the client. Hell, they wouldn’t meet him for another three years.”

The petition that launched the case, and that would evolve into the federal court title Hamdan v. Rumsfeld, was filed in Seattle in April 2004. It challenged the White House’s assertion of unprecedented legal sway over enemy combatants. His client, Swift told the court, was being held in solitary confinement until he agreed to plead to an unspecified offense. Swift termed it a “legal black hole” in which “a factually innocent person can be found guilty.” His client just wanted a fair trial, he argued.

Within a month, representatives from the U.S. Solicitor General’s office showed up in Seattle for a status hearing. “A status hearing?” says Schneider. “The Solicitor General usually doesn’t appear in a case until it’s well underway. I guess we got their attention.”

U.S. Federal Judge Robert Lasnik issued an order outlining how the trial would proceed, displaying a hint of favorable sentiment toward Hamdan’s case, the defense team felt. Lasnik thought it was appropriate that such a potentially landmark case was being heard in the new federal courthouse on Stewart Street, since similarly important wartime cases involving the detention of Japanese-American citizens during WWII had also been heard in Seattle, at the old courthouse on Fifth Avenue.

But Lasnik never got a chance to hear the Hamdan case. The U. S. Supreme Court, after reviewing a separate case, announced that federal courts indeed had jurisdiction to rule on Guantanamo. The high court also decided that all such cases would be heard in D.C. federal court, where Hamdan’s case was transferred in late 2004. That’s when D.C. District Judge James Robertson, a onetime Navy officer, surprised the defense and the White House by siding with Hamdan and invalidating Bush’s Gitmo plan. Detainees should, he agreed, be tried according to military law and the Geneva Conventions. The proceedings against Hamdan came to a full stop in Gitmo.

Professor Katyal argued the case before Robertson, but it was a short-lived victory: The U.S. expedited an appeal, and nine months later the D. C. circuit court unanimously reversed Robertson’s decision. Bush had the right to try designated terrorists, the court decided, without providing constitutionally guaranteed due-process protections.

Among the three judges who reached that decision was John Roberts. Hours after the order was released on July 15, 2005, Roberts drove to the White House and met with Bush, according to later news reports. The following Tuesday, Bush nominated Roberts to the Supreme Court. He was subsequently approved to fill the seat vacated by the late Chief Justice William Rehnquist.

Hamdan co-counsel Schneider says the timing of those events “gave me pause.” Still, he thinks Roberts would likely have ruled the same. Even if he hadn’t, they still would have lost, 2-1. Besides, Roberts’ appointment could be seen as a boost to Hamdan’s case. Like Roberts, Hamdan v. Rumsfeld was also headed to the Supreme Court: The legal team immediately petitioned the high court for a review, and the case was accepted. When oral arguments began on March 28, 2006, Chief Justice Roberts left the bench before arguments began. Because he had heard the case at the lower level, the justice most likely to vote against Hamdan was forced to recuse himself.

With eight justices sitting (a 4-4 vote would leave the lower court ruling intact), Katyal got up to argue once more on behalf of bin Laden’s driver, while Swift, McMillan, and Sipos listened anxiously in the front row (Schneider was in Seattle due to a family illness).

The government had created a “military commission that is literally unburdened by the laws, Constitution, and treaties of the United States,” Katyal said. “If this were like a [civilian] criminal proceeding, we wouldn’t be here.” Katyal was repeatedly asked by the justices for his take on the congressionally approved Detainee Treatment Act that made Gitmo-style law possible, and on its conflict with the Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ). As Justice Antonin Scalia queried: “You acknowledge the existence of things called commissions. Or don’t you?”

Katyal: We do.

Scalia: What is the use of them if they have to follow all of the procedures required by the UCMJ? I mean, I thought that the whole object was to have a different procedure.

Katyal: Justice Scalia, that’s what the government would like you to believe. I don’t think that’s true. The historical relationship has been that military commissions in courts-martial follow the same procedures.

The U.S., represented by Solicitor General Paul Clement, argued that the executive branch has long exercised authority to try enemy combatants by military commissions. “That authority was part and parcel of George Washington’s authority as commander in chief of the Revolutionary Forces,” Clement said.

Scalia noted that the high court doesn’t normally intervene in habeas corpus, in which a prisoner seeks to have his day in court, until after the case is concluded. “I mean . . . this is not a, you know, a necktie party,” Scalia said.

That’s what the Hamdan team felt Gitmo was, however. Justice Stephen Breyer seemed to express similar reservations, wondering aloud if the legislation that approved the Bush-created military commission effectively suspended the guarantee of a right to trial. How could it be “constitutional for Congress, without suspending the writ of habeas corpus,” to approve the Gitmo proceedings? he posited. Justice David Souter then chimed in, observing that “we will have to face the serious constitutional question of whether Congress can, in fact, limit [federal] jurisdiction without suspending habeas corpus.” As Clement fumbled for a response, Justice John Paul Stevens joined the chorus.

Stevens: May I just ask this, just to clarify? When they do take away some jurisdiction of some habeas corpus claims, do you defend that, in part, as a permissible exercise of the power to suspend the writ, or do you say it is not a suspension of the writ?

Clement: I think both, ultimately. I mean, I don’t think—

Stevens: It can’t be both. [Laughter, much of it from the front row.]

A decision came quickly. On June 29, 2006, it was announced that Hamdan had won, 5-3. “Brushing aside administration pleas not to second-guess the commander in chief during wartime,” The Washington Post reported, “a five-justice majority ruled that the commissions, which were outlined by Bush in a military order on Nov. 13, 2001, were neither authorized by federal law nor required by military necessity, and ran afoul of the Geneva Conventions.”

As a result, the Gitmo military commission could not try Hamdan or other prisoners unless the president either established rules requiring the commission to follow military courts-martial procedures or got Congress’ permission to proceed otherwise.

Hamdan’s team was elated. But not Hamdan. He was back in limbo, locked in solitary without an opportunity to prove himself innocent. The military allowed the attorneys to make a conference call to Hamdan in Gitmo. “At one point,” says Schneider, “I believe it was Neal Katyal who said, ‘Salim, you won. You should be very happy. Your name is going to be in our law books forever. Hundreds of years from now law students will be reading your name.’ “

“Maybe I change my name,” replied Hamdan. “I just want to go home.”

In the fall of 2006, Bush acceded to the Supreme Court and got legislative approval from Congress to proceed at Gitmo with something of a hybrid system for the military tribunals. The rules generally followed military law, but hearsay evidence could be admitted and secret testimony would be allowed. Most important, the new law stripped U.S. courts of jurisdiction in detainee cases. That effectively put Hamdan “right back where we started,” says Swift.

The Pentagon also shuffled things around in its Office of Military Commissions, appointing a new trial-system supervisor. As the convening authority, the office approved or rejected charges, and could make plea deals and reduce sentences. In April 2007, it finally charged Hamdan with conspiracy to commit terrorism and with providing material support for terrorism. He was one of several charged, but would be the first to go to trial.

Prosecutors accused Hamdan of conspiring not only with bin Laden, but with Ayman al-Zawahiri and other al-Qaida figures linked to the 1998 U.S. embassy bombings and the October 2000 attack on the USS Cole. Hamdan was in on those acts, in the government’s view, not because he necessarily participated in them, but because he was part of the terrorist cabal. He had provided material support by driving bin Laden. He would face trial in 2008.

To critics, it was a stretch. They were suspicious of the reorganized commissions office as well, after Col. Morris D. Davis was booted from his prosecutor’s job in the fall of 2007. He complained about having been pressured to speed up cases and get convictions because the election season approached. He said he was told “We can’t have acquittals. We’ve been holding these guys for years. How can we explain acquittals? We have to have convictions.” The government denied Davis’ accusations. But he would repeat them under oath in April 2008, and would be one of dozens of witnesses as Salim Ahmed Hamdan got his long-awaited day in court.

By then, Hamdan’s defense team had changed. After the Supreme Court win, Swift left the Navy (he was passed over for promotion and, because of the service’s “up or out” rule, was forced to retire), becoming an instructor at Emory University in Atlanta. Navy JAG officer Brian Mizer was appointed to replace him as Hamdan’s Gitmo counsel. Neal Katyal took on a subsidiary role, working on appeal issues.

Harry Schneider had thought the Supreme Court ruling was likely the end of his involvement with Hamdan. “I never signed up to do the criminal case. I signed up in 2004 to do that civil case,” says Schneider. But after four years of battling and finding his client still locked away, the case had become a challenge he, McMillan, and the firm had to see to the end. “In for a nickel, in for a dime,” Schneider says.

And in for a rough ride. In 2007, Charles Stimson, a Pentagon official overseeing detainee affairs, urged corporations to fire any law firms that worked for them if the firms had clients at Gitmo. A Gitmo prosecutor also took a shot directly at Perkins for representing Hamdan, calling it shameful considering that Perkins also represented Boeing, which lost three employees in the Pentagon 9/11 crash.

But Bob Giles, Perkins’ managing partner, says he received more e-mails about the Hamdan case “than I have received on any other topic during my entire 27 years as managing partner. Sure, there were a few negative e-mails about supporting terrorists, but the great majority of the messages, hundreds of e-mails—including a surprising number from members of the U.S. military—were entirely supportive of our decision and our efforts to uphold the rule of law even as it applies to those deemed our enemies. After all, we were trying to uphold principles that we hope would apply to our own service personnel if captured by the enemy, as well as to those we captured.”

Adds Swift: “Perkins Coie had been representing the titans of industry for a century. But they fought for a principle all the way for this little guy. After the Supreme Court, at different stages, I fell off the team, others fell off. You know who never fell off? Perkins. Once they took it, they were going to finish it, and that to me was extraordinary. It changed things in the industry. It became fashionable afterward to take a Gitmo case. I swear to God, there wasn’t a firm on Wall Street or down in D.C. that didn’t have at least one Gitmo client after that.”

For that matter, Swift fell back into the case. On his own dime, he rejoined the team for the Guantanamo trial, bunking, like the others, in trailers on the isolated military base and spending his days in trial or conferences. They’d get away now and then to the beach, but the walled-off base was short on luxuries as well as newspapers and TV. Schneider, who thought of it as “like living in another world,” says Swift “spent 30 days at the Gitmo trial pro bono. That was a bigger financial hardship for him personally than it was for a big firm like ours.”

All of them immediately took to new military counsel Mizer, who was equally devoted to the cause. Schneider and McMillan pitched in to argue motions and take up questioning on specific issues. Swift handled jury selection and would do the closing argument. The jury consisted of officers picked from a pool formed by the Pentagon. The judge was Keith Allred, a Navy captain.

Hamdan, who denied the charges for which he’d been held officially at Gitmo for more than five years (but a captive since 2001), was being prosecuted under quasi-military law by the Pentagon, defended by a U.S. Navy officer, tried by a military jury, and judged by a Navy officer—all of whom were at war against the organization to which Hamdan allegedly belonged.

On August 6, 2008, after a day and a half of deliberation, the military panel found Hamdan not guilty of the most serious charge, conspiracy, convicting him only of providing material support.

“We were ecstatic,” Schneider recalls. Hamdan, however, was devastated. All he heard was the world ‘guilty,’ and he broke down completely, weeping openly, unable to raise his head.”

Hamdan was inconsolable and couldn’t speak, not even to Chuck Schmitz, the team’s interpreter. Schneider and Schmitz went later to visit Hamdan in a courthouse holding cell. “He was lying on the floor, in a fetal position, still unable to recover from what he considered a fatal blow to his chance of ever leaving Guantanamo,” recalls Schneider. He thought he’d never see his family again, including a daughter he had yet to meet. (His wife had been eight months pregnant when he dropped her off at the Pakistani border the day he was later taken into custody in Afghanistan.) Schmitz and Schneider tried to explain he was in a better legal position, but Hamdan figured he would die in custody.

“We all felt he would be convicted of the lesser charge,” says Schneider. “The whole ballgame came down to sentencing. The government sought life. Charlie made a great argument for credit for time served.”

The next day, the jury announced it was recommending a 5 1⁄2 year term, but with 60 months and eight days credited for time served. In just over five months, Hamdan would be set free.

In Arabic, a grateful Hamdan stood, asked for permission to speak, apologized for any wrongdoing, then thanked the jury. Judge Allred—who deemed Hamdan a “small player” in bin Laden’s network—told him, “I wish you Godspeed, Mr. Hamdan. I hope the day comes when you return to your wife, your daughters, and your country.” Hamdan responded “Inshallah”—Arabic for “God willing.” Before the translation was made over courtroom loudspeakers, Allred replied, “Inshallah.”

The source of the missiles in Hamdan’s car remained a mystery. He claimed he took a car from the pool that day unaware that weapons were in the trunk. The defense also got an FBI agent to say that his investigation showed that bin Laden had personally paid Hamdan out of his own pocket—that in effect he was a servant, not a terrorist. As for the agent who said Hamdan admitted he’d pledged bay’at—allegiance—to bin Laden, he didn’t seem to notice that his Arabic notes, enlarged on a courtroom screen, were being displayed upside down, until the defense pointed it out to him.

Afterward, Comedy Central’s Stephen Colbert called the chauffeur’s trial “the most historic session of traffic court ever.” For its next act, Colbert said, the government hoped to “track down Ayman al-Zawahiri’s dermatologist.”

A month after the initial verdict, the government asked for a new sentencing hearing, hoping to add six years to Hamdan’s term. Allred rejected the move. In November, the U.S. acquiesced, allowing Hamdan to serve his final few months in a Yemeni prison. He was released in early 2009, and reunited with his family in Sanaa, Yemen.

On October 16 of this year, Hamdan was cleared altogether. The D.C. circuit court vacated the material-support conviction based on an appeal argued by Joe McMillan, contending that the acts Hamdan was charged with were not crimes at the time he committed them (constituting improper ex post facto prosecution). The case remains active today, however, while the government considers taking it to the Supreme Court.

During his 2008 presidential campaign, Barack Obama promised to close Guantanamo and end the military trials. He failed, and the issue was rarely raised this year as he campaigned for re-election. Gitmo’s closure is now on the back burner, with about 165 detainees remaining.

Hamdan’s saga has piqued cinematic interest, already inspiring an acclaimed documentary, The Oath, in 2010. George Clooney has bought the rights to The Challenge, a book about the Supreme Court case by journalist Jonathan Mahler, written prior to Hamdan’s 2008 Gitmo trial. A movie script is being drawn up by Oscar winner Aaron Sorkin, with Clooney and Matt Damon set to star. It’s unclear whether bin Laden’s driver will share in the profits.

Hamdan, now 42, has stayed in touch with some of his attorneys, sending occasional e-mail updates, including notification in 2010 that his wife gave birth to a son. In the spring of 2009, while in the Middle East for meetings, Schneider, McMillan, Mizer, and translator Schmitz met in Dubai and flew together to Sanaa for a reunion with their client. Hamdan’s daughters came running to meet them at the airport, followed by a beaming Hamdan. “It was quite a sight,” Schneider recalls, “very emotional.”

The foursome stayed a week, exploring Yemen, with Hamdan showing them the sights. “I will tell you one thing about Salim Hamdan that I learned on that trip,” says Schneider. “He is a very good driver.”