On Nov. 1, the city of Bellevue is expected to issue building permits for an ambitious new performance space called the Tate-uchi Center. The city received 900 pages of blueprints for the facility, which is to hold a 2,000-seat concert hall plus an intimate cabaret venue, and intends to attract “world-class” performers, including the Seattle Symphony and the Pacific Northwest Ballet.

The Tateuchi Center has already drawn national press attention. Last year, The New York Times wrote about the organization’s planned policy of allowing audience members to text, tweet, and access Facebook during shows.

Yet when exactly the center will be built—or even if it will be built at all—remains in question.

After a decade of fundraising, the center still has nearly $100 million to raise to meet its $160 million target. Even with prominent backers, most notably Bellevue real-estate magnate Kemper Freeman, fund-raising has been painfully slow. “It’s like trying to sail a sailboat directly into a gale,” concedes executive director John Haynes.

Over the past year, the center has cut operating expenses in half, according to an e-mail Haynes sent to supporters this summer, obtained by Seattle Weekly. Though Haynes once led a staff of 10, that’s now down to three, including himself.

“They keep thanking us for keeping the faith,” says Janis Wold, former secretary of a fundraising volunteer “guild” for the center. But, she says, doing that “is getting harder.”

One day last week, Haynes showed off an architectural rendering and other displays of the planned facility meant to keep the faith alive. The presentation center is located inside the Hyatt Regency in downtown Belle-vue, where the Tateuchi Center is slated to be built. An entrance to the facility is actually planned for inside the Hyatt, at one end of the hotel’s plush lobby.

Behind this rendering is a room containing seats like those planned for the concert hall. “They’ll be made from cherry,” Haynes says, rubbing a hand against the wood. The fabric on the seats is to be designed with a pattern inspired by a plant that grows alongside local creeks. When the interior designer visited, Haynes explains, she left with the feeling that Bellevue wasn’t a typical city with a park in it, it was a park with a city in it. So her designs draw from nature, like a colorful rug that is meant to evoke a forest floor. At the same time, Haynes says, the designs pay homage to the Eastside’s high-tech community. Decorative trim on the walls is meant to mimic a circuit board.

Huge pictures in the presentation center imagine performances to come. “There will be nothing in King County like it,” Haynes says, referring to the variety of acts planned for the facility. “There could be Willie Nelson one night and the Seattle Symphony the next.”

The concept was born of the long-standing belief that the Eastside no longer constitutes merely a bedroom community for Seattle, but is rather a “very large metropolitan area” in its own right, says Bellevue investor and Tateuchi board chair Peter Horvitz. Not only does the region deserve its own major arts center, Horvitz says, but worsening traffic—and now tolls—have made it harder for Eastsiders to get to Seattle venues.

In fact, research shows that Seattle arts institutions have been losing Eastside audience members at a rate of about 10 percent a year—which is why organizations like the Seattle Symphony and PNB embraced an Eastside venue as a way to recapture that audience, according to Horvitz.

In 2002, Freeman kicked off a campaign to build the Performing Arts Center Eastside (PACE), as the concept was then called, by donating the $8 million parcel of land adjacent to the Hyatt. A $6 million donation from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation spurred further planning, including the hiring of Norm Pfeiffer, a Los Angeles architect with roots on the Eastside.

Pfeiffer had worked with Haynes on the building of a $70 million arts center at the University of Notre Dame. Haynes says it was Pfeiffer who recommended him to the PACE board. Haynes not only built the Notre Dame facility from the ground up, but had previously served as president of an arts center in San Diego County, Calif., and before that as a executive at CBS.

He arrived in Bellevue in 2007. The recession, of course, was hot on his tail—the reason he and Tateuchi board members give for the stalled progress despite the Eastside’s abundance of wealthy potential donors. “They’re dealing with the kind of anxiety they’ve never dealt with before,” Haynes says of the millionaires and billionaires he’s asked for money. “I’ve had people say to me, ‘I’m afraid that Spain is going to bring the entire banking system down.’ A month before that, it was Greece. Before that, it was Italy.” At the same time, he says such people are focused on keeping arts institutions they already contribute to alive through the recession rather than building an entirely new organization.

Even so, a wealthy widow named Ina Tateuchi gave the project its most significant pledge—$25 million—in 2010, also resulting in a name change for the planned center. Tateuchi and her late husband, businessman Atsuhiko Tateuchi, had lived for many years in Japan, where cities support “dozens” of arts institutions apiece, according to Tateuchi Foundation administrator Dan Asher.

Jim Tune, the former CEO of ArtsFund, the grant-making group, says he thought the Tateuchi gift would be similar to the one given the Seattle Symphony by Jack Benaroya, which triggered other multimillion-dollar donations and jump-started the orchestra’s campaign for a new concert hall. But more gifts of that magnitude did not materialize. In the past couple of years, Haynes says, the Tateuchi Center has raised “a couple of million dollars a year, which is great if you’re running a theater, but not if you’re trying to build one.”

A year ago, the board decided to focus all its efforts on chasing donations of more than a million dollars. That meant putting its two fundraising guilds on “temporary inactive status,” according to Haynes’ recent letter to supporters. The guilds had put on special events for potential donors, like candlelight dinners. While scuttling fundraising efforts in order to raise more money might seem counterintuitive, Haynes says that the events took many months of planning and netted maybe $150,000 or $200,000 apiece. Even supposing that an event could clear $500,000, he says, “I would need 199 special events” to make the math work. “We’d be done in a hundred years.”

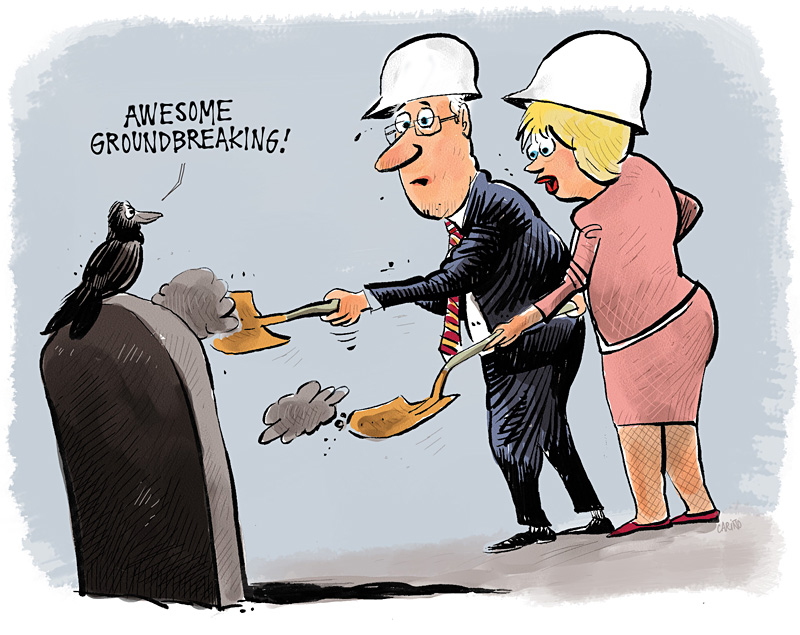

The move deflated some supporters, though. “I was very disappointed when the guilds were put on hiatus,” says Wold, who had organized one dinner for 400. She says she understands that the center might need a different fundraising strategy, but she wonders whether it has yet hit upon a winning formula. “It’s been a while and nothing’s happened,” she says. She notes that the center “was supposed to be open by now,” but the date for groundbreaking “has been a moving target.”

Indeed, while the Times and other media have reported that the center is currently scheduled to open in 2014, Haynes, questioned about a realistic timetable, says he won’t give a target date anymore. He maintains that 2014 is possible. Asked whether it’s also possible that the effort might fail, he says, “I suppose it’s conceivable.”

Some, including Wold, wonder whether Haynes should continue at the helm, given the slow progress and his high salary—roughly $250,000 a year. But Horvitz says the board remains satisfied with Haynes, and recently renewed his contract. The businessman says fundraising is as much the board’s responsibility as Haynes’.

Board member Jim Hebert admits he’s had his doubts about the feasibility of such an expensive project. A few years ago, he says, he voiced the idea that the board should scale back the concept. “Other trustees disagreed with me,” he says, adding that he came to the conclusion that they were right. “The fact that we have weathered the Great Recession and stayed the course” makes him optimistic, he says.

Horvitz also says he remains optimistic. He asserts that the $63 million raised so far “is the largest amount ever raised for an Eastside project.” Of that $63 million, $12 million has already gone toward development costs.

At the same time, Horvitz concedes that “this is where the rubber meets the road. Everything else is done except raising the money.” And fundraising, he says, “can’t go on forever,” adding that some Eastsiders already wonder whether the project can raise the kind of money it needs, and are reluctant to contribute until they see more headway. “We recognize we have to—I’m going to say in the next year—make some major progress that shows we can get this done.”