“Jury duty,” teenager Caleb Chase typed to his Twitter followers on Monday, Sept. 27, 2010. “Quite likely going to end up being one of the jurors for an extremely long case.”

He did, and it was. And it continues, thanks in part to that and other tweets.

The murder trial of Michiel Oakes, accused of killing dog-trainer-to-the-stars Mark Stover in a love/hate triangle, lasted most of a month, watched closely by an American TV and newspaper audience tuned to the daily revelations of a complicated small-town murder mystery. Labeled in some news accounts as “Seattle’s Dog Whisperer,” Stover had a dominating psychological kinship with animals. Communing on their level, he first trained a dog to behave, then its owner. His success brought him wealth and such clients as Starbucks CEO Howard Schultz, musician Eddie Vedder, and Mariner Ichiro Suzuki.

But it was untamed human relationships that led to his 2009 murder in Anacortes. Linda Opdycke, Stover’s wife of three years, had divorced him, then accused him of stalking her.

Oakes, Opdycke’s lover—he was her “Knight,” trying to “win the hand of the princess,” a judge would later say—shot Stover and pumped three bullets into his guard dog at Stover’s Anacortes home and kennel. The dog lived while Stover died, his body never found.

John Henry Browne, a Seattle attorney with a fondness for hyperbole, defended Oakes, calling him a victim and belittling the deceased Stover as a “domestic-violence terrorist.” Oakes was claiming self defense, offering up a dented armored vest that indicated it had been hit by a round from Stover’s gun. But prosecutors said that not only was Stover unarmed and killed in cold blood, but someone likely hired Oakes to take out the dog whisperer. Opdycke denied it was her or her wealthy father.

A jury would decide, and Caleb Chase had become a member of it.

“On jury trial that is expected 4-5 weeks,” the religious, 19-year-old church guitarist told friends via Twitter Sept. 29, 2010, the day the trial began in Skagit County Superior Court in Mount Vernon. “Wow, talk about intense. This is going to be an interesting month.”

The trial would wind up Oct. 22 with Chase and his fellow jurors rendering a unanimous guilty verdict on the first vote. Oakes, still professing his innocence, was sentenced to 26 years and is now in the state penitentiary at Walla Walla.

As Chase would tell followers on his Twitter feed that day: “Oh, and Dateline [NBC] wants to interview any/all of us on the jury. I’m think[ing] that I will probably say yes.”

The defense, judge, and prosecutors recently learned that Chase had sent at least 20 tweets throughout the four-week trial, and they’ve now become the basis for an appeal by the man he helped convict.

Papers were filed in Skagit County last month alleging that Chase’s tweets violated Oakes’ right to due process and a fair and impartial jury. The fate of the dog whisperer’s murder case now rests in part on the silent messages of a tweeting juror.

Though other social-media issues have been argued on appeal, this is thought to be the first Twitter appeals case in state history. “During the 17 years I served on the Supreme Court of Washington,” says recently retired Chief Justice Gerry Alexander, “the court was never confronted with a case where a juror was tweeting during a time when the juror was empaneled.”

But social media are having a growing impact on court cases here and elsewhere. “Most states have updated their jury instructions to tell jurors not to use the Internet or social media,” says Eric Robinson, deputy director of the Donald W. Reynolds National Center for Courts and Media at the University of Nevada-Reno. “A few courts—the best, in my opinion—also explain the rationale for this decision. Of course, even if these warnings are included in the jury instructions, it’s hard to know how many judges are actually using them.”

Oakes’ appeal attorney, Suzanne Lee Elliott of Seattle, says she hopes to be granted a hearing on the issue this month or next. She has delayed filing an opening brief with the state appellate court, and is first appealing to the original trial court in Mount Vernon to grant a new trial. Besides the charge of juror tweeting, she is raising another new issue, claiming Oakes was denied due process by being arraigned for Stover’s murder in a closed courtroom without an attorney present.

Both issues were discovered after the trial, she says. Oakes’ brother, Tim Oakes, read about a recent landmark Arkansas Supreme Court decision that reversed the conviction of a death-row inmate because a juror had been tweeting during the trial. Tim then searched the Internet to see if jurors in his brother’s case had tweeted, discovering the posts on Chase’s Twitter page.

“If the [Skagit] judge denies our motion, then we’ll include these new issues in our brief to the court of appeals,” seeking a new trial at that level, Elliott said last week. “But we see them as extremely important issues for appeal.”

Asked about the issues, Skagit County senior deputy prosecutor Rosemary Kaholokula, who headed the Oakes prosecution team, said “We have not yet filed a response, and no, we have no comment.”

On his Twitter page (@chasecaleb), Chase describes himself as “a hardcore, radical Jesus addict. He is what I’m all about.” He’s posted more than 1,600 tweets and has 94 followers. He links to a website as well, where he regularly posts and discusses Bible verses.

A sound engineer, Chase lives in Auburn and works for a church, the International House of Prayer Northwest in Federal Way, which he refers to as IHOP in his tweets. He says he’s stunned to learn his Twitter “ramblings” could lead to the reversal of an outcome he thinks was just.

“I recall the judge making a big deal out of not talking to anyone, and we all took it very seriously,” says Chase, now 20. “I don’t recall the tweets, other than they were nothing very relatable or identifiable to the trial, other than telling people I was on jury duty.”

Chase says he tweeted from the jury room and could have been using either his smartphone or a laptop he’d brought. But as he points out, he doesn’t appear to have commented directly on the trial itself, nor revealed jury discussions or his own feelings on Oakes’ innocence or guilt.

As the trial began on Sept. 29, for example, he tweeted, “Jury panel room has fresh coffee, water bottles, sodas and an assortment of muffins and hard candy. Not bad!” He then responded to a tweet from one of his Twitter followers, “Oh, I know, donuts tomorrow. The bailiff will basically do/get anything for us that the budget can fit.”

But in her brief for a new trial, Elliott argues that Chase and the other jurors had been warned by the judge not to discuss any aspects of the trial with persons other than jury members. And though the tweets never specifically reveal on which case Chase is sitting, some of his followers or anyone visiting his Twitter page might have been able to match the Oakes case to his Twitter clues, since the trial was generating daily headlines.

“Well,” says Chase, “they make it sound like I’m sitting there in the jury box with my phone in my hand, and that’s certainly untrue.”

Besides, he asks, how could a few innocuous tweets cancel out all that impressive evidence piled up by prosecutors against Michiel Oakes? “From my perspective as a juror, the case was laid out clearly, and once we started to piece it together, the outcome was obvious, and we all, I assume, stand by it today.”

On the trial’s opening day, the state laid out its case, claiming Oakes arrived at Stover’s home wearing an armored vest and bringing weights, rope, and camouflage material to use in disposing of the body. As The Seattle Times reported then, prosecutor Kaholokula introduced the case’s main cast of characters: Renowned dog trainer Stover, 57; his ex-wife Opdycke, 45, the daughter of wealthy Eastside businessman Wally Opdycke, who once co-owned Chateau Ste. Michelle winery and ski manufacturer K2 Corp; and Oakes, 42, a security buff whom Linda Opdycke hired as her bodyguard and later took as her lover.

“Mark loved her very much,” Kaholokula told the courtroom, and was devastated by their 2008 divorce. “He behaved stupidly,” she said, “continuing to make contact with her that culminated with Mark rummaging through rubbish at her house” in Winthrop.

That led to a stalking conviction for Stover in Okanogan County that forced him to give up the several firearms he owned. He eventually moved on and found someone else to love, the prosecutor said. But Opdycke “maintained, or formulated, some belief that she was in danger from Mark,” Kaholokula said. “She was armed to the teeth. She trained guard dogs and had security around her house.”

She also hired Oakes to protect her. Throughout the trial and afterward, prosecutors and investigators suggested Opdycke had a hand in sending Oakes to Stover’s home, but she has vigorously denied any role in the murder.

That first day was apparently a trying one for juror Chase. As he later tweeted, “I’m trying not to blow up at my family. Jury duty all day then worship practice…not enough space for an introvert.” (He was then commuting from Skagit County to the church in Federal Way.)

As the prosecution moved forward, evidence of Stover’s blood in Oakes’ car was introduced, along with other factors intended to show Oakes had planned the killing. Approaching Stover’s home, Oakes reportedly shot Stover’s dog, Dingo, three times in the head, then killed Stover inside the home. (Dingo has since died of cancer.)

Only a few days into testimony, Chase tweeted, “Pretty sure I’m way past exhausted. Eight hours of jury duty, six hours of driving, and four hours at IHOP. Wow.”

Then things seemed to smooth out.

Oct. 6: “Cake in the jury room,” with a smiley face.

Oct. 7: “Played Apples to Apples [a party game] for an hour during jury duty.”

Oct. 11: “I’m on jury duty right now,” later adding: “2.5 hour lunch break: massive win.”

By then, the prosecution had rested, and local defense attorney Corbin Volluz, co-counsel with Browne, was telling jurors they were about to hear “the rest of the story,” including Opdycke’s “nightmare with Mark Stover,” according to news reports.

She was always armed, even sleeping with a gun, Volluz told the court. Then she hired Oakes as backup. He had gone to Stover’s home to reason with him, only to find himself in the middle of a gun battle for his life.

On the witness stand, Opdycke painted Stover as a dangerous man, recalling a night when “I woke up with Mark in my bedroom . . . And he had a pistol in his hand, and laid it on the pillow next to my head.”

The prosecutor questioned Opdycke’s motives in testifying for Oakes. If she could help her boyfriend establish a self-defense case, Opdycke was asked, wouldn’t that get her off the hook, too?

“What do you mean by that?” Opdycke asked.

“If a jury were to find that this was self-defense, you wouldn’t have any more liability, either,” said Kaholokula.

“I have no liability in this case,” said Opdycke.

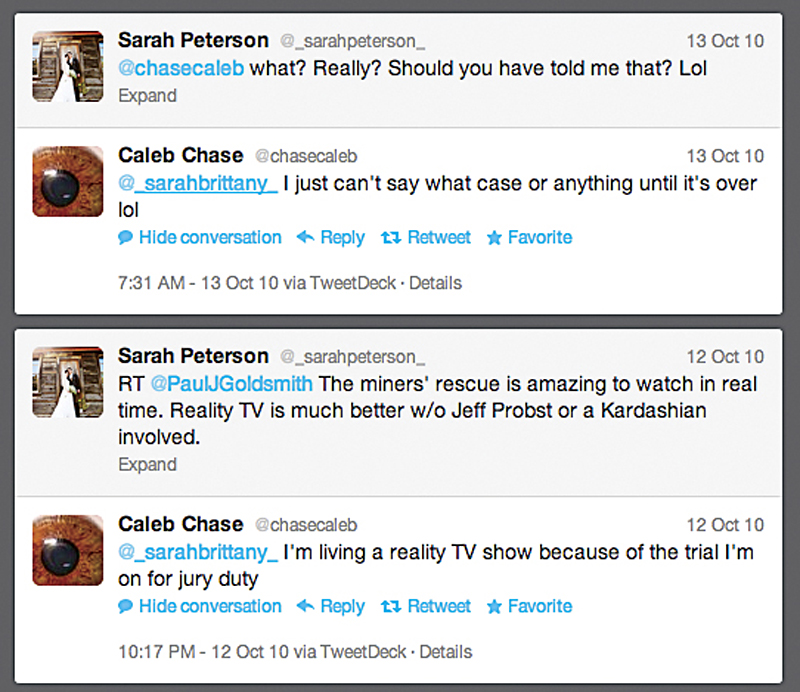

It was a dramatic point in the trial, with the defendant, Oakes, about to to testify. Tweeted Chase on Oct. 12: “I’m living a reality-TV show because of the trial I’m on for jury duty,” later adding to a follower who asked about the case, “I just can’t say what case or anything until it’s over lol.”

That day, Oakes was sworn in and told his self-defense story: Stover had demanded they meet at Stover’s home, where Oakes hoped to settle things peacefully, though he took the precaution of wearing a Kevlar vest. He planned to ask the dog whisperer to back off from Linda, when Stover—though he was prohibited from having firearms—produced a gun.

“He caught me totally by surprise and shot me in the vest and he was not wearing Kevlar and he was shot,” said Oakes. He then shot Stover’s dog after it attacked him, he said.

Oakes panicked, he said. Rather than call police, he tried to cover up the crime, dumping Stover’s body into the nearby Swinomish Channel at Padilla Bay, just behind the Swinomish Casino and Lodge.

But, contrary to Oakes’ testimony, prosecutors and investigators contended he shot a hole in his own vest to suggest Stover had fired at him. They also felt he didn’t dump the body where he said he did. Were they to find it, said Skagit County Sheriff’s detective Dan Luvera, “It’s gonna tell us that Mark was probably shot in the back of the head or in the side of the head. It’s gonna tell us stories that Michiel Oakes does not want us to know.”

As the case went to the jury, Chase tweeted on Oct. 15, “Jury duty wisdom of the day: boats are cheaper than wives.”

The following Monday, the 12- member panel was confined to the jury room on the first day of deliberations. No one on the outside knew what was happening. But Chase let his followers know that, whichever case he was sitting on, jurors were not totally bogged down in legal debate.

“Wow,” he tweeted. “Sitting in the jury duty room listening to people casually having a conversation about new age rituals and no clue what to say.”

The second day, responding to a follower who tweeted she was tired, he wrote: “UG me too. Exhausted to the max from jury duty plus running sound at church plus playing at IHOP plus driving equals 65-75 hours a week.”

The guilty verdict was announced on Oct. 22, 2010, to a packed courtroom. Oakes took it quietly, hugging his three children from a former marriage, while some in the audience cheered. Judge Mike Rickert would later hand down the 26-year sentence, describing the killing as a variation on a story from the ages: “How does the Knight win the hand of the princess? He goes out and he slays the dragon.”

Still, Rickert added, “I almost have more questions now than I had when we picked the jury. I don’t know where Mr. Stover is, but I’m pretty sure I know where he isn’t, and that’s off the dock at the end of the Swinomish Channel.”

Caleb Chase wound up his trial tweets on the final day with a flourish: “Finished jury today. Defendant was convicted. It was an intense four weeks.”

Followed by: “It was a first-degree murder trial of Oakes. He was convicted for killing T. Mark Stover, a famous dog trainer.”

“It was covered by local news plus four national shows, including Dateline and 48 Hours. Dateline wants to interview me.”

Later on, he sent a hyperlink: “Seattle Times article on the case I was on jury.”

His final related tweet, according to court filings, was Nov. 15, after the Skagit Valley Herald published a picture of jurors and reported on their deliberations.

“Made it on the front page of the county newspaper yesterday, big color picture and everything!” he wrote, adding in a follow-up, “Yes. That’s me on the front page. I feel so special.” He also linked to his Tumblr site, which featured a picture taken of the front page.

“I don’t believe the judge said anything about not tweeting,” Chase now says. “And if he had, I certainly wouldn’t have done it otherwise.”

Did any other jurors tweet? “If they did, I don’t have a clue.”

In her argument for a new trial for Oakes, attorney Elliott observes that the Oct. 18 tweet, in which jurors talked about “new age rituals,” effectively “revealed jury-room discussions on the very day the case had been given to the jury for deliberations. This was despite repeated warnings from the trial judge instructing the jurors not to discuss the case.” Such “conduct undercut the right to a fair and impartial jury. Mr. Oakes should be granted a new trial, at which further precautions can be taken to avoid similar problems,” Elliott says.

New precautions may be in order either way, agrees legal expert Robinson in an e-mail. “There are an increasing number of cases [nationwide] in which jurors have been found using the Internet and social media for everything from ‘friending’ fellow jurors to researching legal terms online.” But “in general, courts have allowed verdicts to stand or not declared mistrials in cases where jurors have tweeted, posted Facebook messages, et cetera, as long as the content of the posts has nothing to do with the case and does not reveal anything about the jury’s deliberations.”

That seems the situation in the Oakes case. Still, this past December, the Arkansas Supreme Court reversed a murder conviction and death sentence in a 2010 case where one juror tweeted during the trial, while another fell asleep.

“Both these problems, the court said, constituted juror misconduct requiring reversal and a new trial,” Robinson points out. “The court was particularly concerned about one of the juror’s tweets, ‘Its over,’ sent 50 minutes before the jury informed the court that it had agreed on a sentence.”

The defendant, Erickson Dimas-Martinez, had been convicted in 2010 of robbing and shooting a teenager. The juror’s Twitter feed, followed by at least one journalist, gave “advance notice that the jury had completed its sentencing deliberations before an official announcement was made to the court,” the court ruled.

By contrast, Chase’s most revealing tweets were apparently all made after the verdict was announced. Chief Justice Alexander says he “would be surprised if a court takes the position that tweeting by a juror automatically justifies a new trial. Over the years I have seen a number of [non-Twitter] cases where it was alleged that the juror was talking about the case with someone during the course of the trial. Those incidents don’t ordinarily result in a new trial unless the juror gained some information they should not have received or he or she expressed their views about the case.

“I, of course, don’t know how Washington courts will look at tweeting,” he adds. “As they say, we shall see.”