In 2008, “Jane,” an engineer living in an apartment on Beacon Hill, saw her rent go up to $1,200 a month. While only 24, she thought she might as well buy a place for that money, rather than see it “continuing to go down the drain.”

She started looking in Seattle, but found prices too high. So she explored Renton, where she worked. There she found a two-bedroom condominium for $175,000. It was nothing fancy, but it had big windows and was near a slick new retail complex called The Landing. She assumed she got a pretty good deal since housing prices had dipped since the height of the bubble. When her boyfriend, also an engineer, became her husband, he moved in.

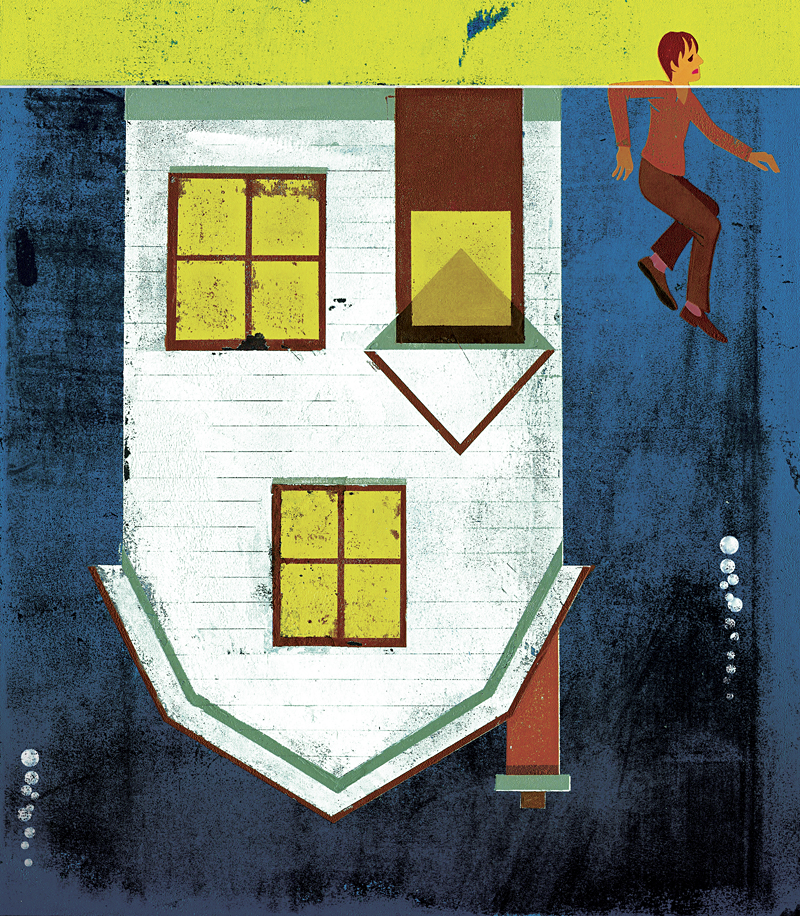

What they didn’t know is that prices would not only continue to drop, but would go into free fall in south King County’s condo market—one that real-estate lawyer Craig Blackmon observes “has been absolutely hammered.”

The couple watched the value of their condo plummet to $80,000, then $70,000, then even lower. A one-bedroom in their 120-unit complex is currently listed at $40,000. In other south King County complexes, some condos are selling for under $30,000.

“It kept me up at nights,” Jane wrote on a blog she started to chronicle the decision she was on the verge of making. “It would depress me at the most random times.” (Wary of provoking her bank, she uses pseudonyms for herself and her husband. “Cory,” on the blog—schrodingershouse.blogspot.com—and asked to be identified that way in this story.)

Unlike millions of Americans caught by disastrous subprime mortgages and their own desire to live above their means, Jane and Cory can easily afford their mortgage, which with taxes runs roughly the same as the rent for her old Beacon Hill apartment. Earning more than $100,000 between them, they could afford at least twice that. The problem is they don’t want to stay in what Jane has taken to calling their “sad little condo”—and if they attempt to sell it, they’re looking at a huge loss.

In February they consulted a lawyer, who asked not to be identified for this article. “Walk away, right now!” the couple recalls the lawyer saying. The attorney indicated that the couple should simply stop making mortgage payments and let the bank foreclose on the property—a course of action, among relatively affluent homeowners, known as a strategic default. In fact, the attorney said that if they were a business, they would be obligated to default. “It would be the right choice for our stockholders,” Cory relates.

Even two or three years ago, they might have received different advice. A 2010 study by Fannie Mae found that 88 percent of respondents believed it was morally wrong to default on one’s mortgage. The business community was solidly behind this moral code, which served their interests. The national conversation then centered on how to keep people in their homes.

But today no one paradigm governs the housing bust, which has given rise to market trends never before seen, unpredictable behavior by banks, and a new morality on the part of homeowners and the professionals who advise them. While local figures on strategic defaults aren’t available, statistics for this state from the Mortgage Bankers Association show that defaults as a whole are at a record high. Washington now has the fifth highest rate of mortgage payments that are more than 90 days past due—remarkable given that in 2007, Washington ranked almost dead last among states. Just a year ago, it placed 20th.

“Why is Washington state going in this direction?” asks Scott Jarvis, director of the state Department of Financial Institutions. “Boeing is going great guns. The last time I checked, Microsoft is still in business. It’s not like we’re in the middle of the Arizona desert.”

One possibility, Jarvis acknowledges, is that a growing number of homeowners can pay their mortgage, but are choosing not to.

Blackmon says such people now constitute “the vast majority” of his clients. Likewise, fellow attorney David Leen says he gets “dozens of calls a day” from people wanting to leave their homes—and mortgages—behind them. He says the calls come from “doctors, lawyers, people with means.”

“Most of the cases I see are not economic hardship,” echoes Lars Neste, another attorney who frequently represents underwater homeowners. “A lot of them have done the math, and realize that the market isn’t going up anytime soon.”

Or if it does go up—and the past few months have seen an uptick in Seattle—they believe it won’t be enough to justify all the money they’ll spend during the life of their mortgages. Says Blackmon: “People might as well be burying money in their backyard.”

As in Jane and Cory’s case, the situation usually sparks tremendous anxiety—which is not to say it doesn’t have an upside. As Blackmon points out, defaulters effectively get to squat in their homes “with zero housing costs.” And because banks have gotten slower and slower at carrying out foreclosures—often because they don’t want the properties either—people are sometimes staying for years in homes they’ve stopped paying for. The rules of the game have changed, if not been thrown out entirely.

For the past two years, Tami and Ron have been living in a stunning $1.4 million house in Shoreline. Their housing costs during that time: zero. That’s not what they intended, though.

The couple tells their convoluted tale one morning while their two children, who know nothing about the situation, are at school. (The desire to protect their kids, as well as anxiety about prompting the bank into further action, leads them to request that they be identified by their first names only.) Their story, Tami admits, highlights the excesses of the bubble as much as the resulting chaos.

Until the bust, Tami and Ron were making a lot of money—particularly Tami, a chatty 42-year-old realtor. Ron, 48, is a lawyer who until recently worked for the federal government. “Our best year, we probably made $300,000,” Tami says, about 70 percent of which came from her income selling houses.

Consequently, they splashed out when, expecting a second child, they decided to tear down their small house and build a bigger one that stretched above a neighboring property to offer sweeping views of Puget Sound. In 2007, they took out a $1.4 million “construction loan” to build the house, which was supposed to roll over into a conventional mortgage after they moved in. They had so much money—and so much faith in the market—that they then bought, for $550,000, another house a few blocks away to live in during the construction.

In July 2009, almost done with construction, they moved into what Ron calls their “forever house,” with the Sound glimmering into almost every room, lots of room for the kids, an expansive kitchen, his-and-hers offices, and a second-floor hallway like a bridge floating through space, connecting the children’s bedrooms on one side with their parents’ on the other.

In December, they let the bank know they were wrapping up construction and ready for the loan to roll over. But by then the bust had kicked in, and banks were being much tighter with mortgage requirements. Still, the couple maintains, the rollover was part of the deal they’d signed in 2007. The bank, according to Tami, told her it should only take a couple of weeks to process. All they had to do was fill in a few more forms to update their income and other information.

The rollover never came through. The couple continued to receive bills for their construction loan. Then, in June 2010, according to bank documents reviewed by Seattle Weekly, they received a jaw-dropping invoice for nearly $1.4 million—the entire balance of their loan.

“Oh, how weird. I better call the bank,” Tami says, characterizing her initial reaction to the whopping bill. At that point, she and Ron stress, they had paid every bill except the one before, an omission they attribute to their concern over why the loan hadn’t yet rolled over.

She says she was told that the bill was no mistake, but was given no explanation. They simply had to pay $1.4 million, plus the $5,000 owed from the month before, within two weeks or they would be in default.

Paying $1.4 million wasn’t an option. They didn’t make that much money. In fact, Tami’s income had dramatically dropped due to the housing crisis as well as the three-month hiatus she’d taken from work while undergoing treatment for thyroid cancer. As for paying the back amount, she says there was no point, given that they would be in default anyway. “Screw you,” she says she thought. “I’m going to keep my $5,000.”

A month later, the couple received a terse e-mail from a loan administrator containing several bullet-pointed reasons why they no longer qualified for a conventional mortgage. “Unacceptable payment history with us” is one, a charge the couple denies except for the one unpaid bill. “Misreps [sic] in file—co- borrower’s employment” is another. The alleged misrepresentations are apparently a reference to the discrepancy between Tami’s income at the time she applied for the construction/rollover loan and her 2010 income, which she says dropped by about half.

The final reason: “Rental property in foreclosure.” This appears to be a reference to the house they bought while building their dream home. And here’s where the bust pulled a double whammy on them: “The market was super-hot,” Tami says, explaining the decision to buy rather than rent a temporary home. “I thought I’d sell it and make $150,000.” Instead, when it came time to sell and move back into house #1, house #2 had lost $75,000.

They ended up doing a short sale, wherein banks agree to let houses sell for less than the mortgages and, in many cases, forgive the difference. Before that, they’d missed close to a dozen payments, cognizant that banks are reluctant to approve short sales if they’re still getting money from homeowners. Tami says the house fleetingly went into foreclosure during that time.

Now Tami and Ron faced a foreclosure on their forever house. They considered walking away, but this was the house they never wanted to leave. So they hired an attorney, Leen, and decided to fight. And they’ve kept living there. “A lot of people would think, ‘Good for you, you’re living rent-free,’ ” Tami says. In reality, she says, “It’s not that cool.”

They went into bankruptcy to put off a foreclosure auction. They achieved a delay, but shot their credit. Ron found the stress “was affecting the quality of my work. I made a decision to leave before anything got worse.” He is now looking for work. Tami also lost her zeal for work, and gained 30 pounds. They’ve largely kept what’s going on a secret, which hasn’t always been easy—like the time a client stopped by just as a bank representative was nailing a foreclosure notice onto the house.

Their castle has more than a few chinks in it, since they hadn’t put the finishing touches on the house when they went into default, and don’t want to put any more money into it until they know they’re keeping it. As they give a tour, they point out the paintings that are covering holes in the walls, the missing range hood that frequently results in a smoke-filled kitchen, the blackened cedar shingles, and the raggedy yard in desperate need of retaining walls—which prompts Tami to describe their home as the “big-ass house with a crappy yard.”

Their predicament has dragged on. A second foreclosure auction was scheduled and then canceled after the state last year passed a law requiring banks to agree to mediation if requested by homeowners. A mediation session was scheduled, delayed, then scheduled again for this past February. A few days before it was to take place, the couple says, the bank called to request another postponement.

Since February, they have heard nothing from the bank. Leen figures they will. The bank, he says, is not going to give Tami and Ron “a free house.”

“We’re in limbo,” Tami says.

Brian Heberling was a Bellevue-based real-estate investor, buying properties and fixing them up or renting them out, when the market started to collapse. As his holdings suddenly lost value, he sensed a new business opportunity. In 2009, he started Nest Financial, with the idea of helping others caught by the downturn. Initially, one line of the business was devoted to securing loan modifications for homeowners—or trying to.

“It was a maddening experience,” Heberling says of dealing with banks. “They wouldn’t modify.” As a stalling tactic, he claims, lenders “would lie and say they didn’t have the paperwork” from homeowners.

Eventually, Heberling devoted himself to the other side of his business: helping people shed their homes. He does this specifically through short sales, and says his five-person operation has now done several hundred.

He markets his business with populist rhetoric. “The banks are not on your side,” his website proclaims, adding that homeowners need a “take-no-prisoners team” to handle these financial sharks. Wearing jeans and an untucked shirt one afternoon as he talks about his business, he evinces the chic/scruffy air of someone who enjoys wrestling with the suits of the financial world. His rhetoric is even sharper in person: He talks about banks “raping the system” and participating in “fraud squared.”

Heberling says he’s spent a lot of time researching the subject. He traveled to the mountains of North Carolina, for instance, to take part in a multiday “boot camp” given by an attorney there named Max Gardner, who over fine meals and single-malt Scotch teaches colleagues how to challenge foreclosures by calling attention to errors by banks, who are often in the process of selling the mortgages to investors. Inside Job, the scathing 2010 documentary that looks at this flawed process of mortgage “securitization”—which entails selling mortgages in investment bundles—is a touchstone for Heberling.

He talks tough about his tactics with banks, saying he’ll tell them to “take it or leave it” when presented with an offer. But part of his strategy has to do with keeping some things to himself. All banks require proof of a homeowner’s “hardship”—backed up by bank statements—before they will sign off on a short sale.

“I don’t lie,” he says. “But I certainly don’t tell them what they don’t need to know.” For instance, he elaborates, “What is the definition of a ‘bank statement’? If a person’s got $250,000 in a retirement account and a bank’s not asking for it, I’m not necessarily going to disclose that.”

Heberling says he’s proudest, however, not of his tangles with banks, but of his role as a kind of morality coach. His clients, he says, have included a “high Microsoft wage earner” and a “prominent Seattle businessman,” who inevitably come to him “shocked and embarrassed.” He tells them “they’ve done nothing wrong,” that a mortgage is “nothing more than a financial contract,” and that “there’s nothing wrong with a homeowner seeking a financial renegotiation.”

Before he gets to that, though, he insists that all his clients buy Underwater Home, a book by University of Arizona law professor Brent White.

In 2008, White was an untenured faculty member who specialized in “social psychology”—in essence, the ways groups of people make decisions. The housing crisis hit Arizona early and hard, and as he watched, he wondered why, given the dramatic loss in value of homes, more people weren’t intentionally defaulting.

“At that point, the default rate was quite low,” White recalls. The statistics he gathered by late 2009 showed that as many as a third of American homeowners were underwater. In Arizona, nearly half of homeowners had homes worth less than they owed; in parts of California, that figure reached 85 percent. (The Seattle area hit the one-third mark in 2011, according to a Zillow.com estimate.) Negative equity sometimes reached into the hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Yet the rate of homeowners defaulting or going into foreclosure was only about 14 percent in 2009, according to Mortgage Bankers Association data. One estimate, published that year in a joint report by consulting firms Experian and Oliver Wyman, suggested that strategic defaults accounted for just a quarter of the 14 percent.

Homeowners’ reluctance to stiff their banks struck White as running counter to economic theory, which holds that people operate in their financial self-interest. He wrote a paper in late 2009 about this disconnect, because, as he puts it now, “that’s what academics do,” especially in their publish-or-perish world.

“Homeowners should be walking away in droves,” he wrote. “But they aren’t.” He argued that people’s “shame and guilt” caused this “irrational” behavior. They were indoctrinated in the deeply held belief that paying one’s mortgage is the right thing to do. They also had an “exaggerated” idea of the consequences of not doing so. “A few years of poor credit need not seriously impact one’s life.”

“I thought a few hundred people might look at it,” White says of his paper. Instead, it set off a national debate. He says he was not intending to present a moral argument, merely a societal analysis. But the moral questions the paper raised by implication were central to its reception. University of Chicago economist Luigi Zingales, in the policy magazine City Journal, warned that the erosion of the social stigma associated with not paying one’s mortgage, which White advised, would lead to “catastrophic results.” Housing prices would fall even further into negative territory. Zingales’ piece was entitled “The Menace of Strategic Default.”

“There’s a moral dimension to this, as homeowners who simply abandon their homes contribute to the destabilization of their neighborhood and community,” echoed Fannie Mae spokesperson Brian Faith in a Washington Post piece about what author Kenneth Harney termed White’s “incendiary core message.”

So White tackled the morality questions head-on in further papers and then, in 2010, Underwater Home. He argued that defaulting on one’s mortgage may in fact be the moral choice—even if one can technically afford it “according to some arbitrary debt-to-income ratio established by the banking industry”—when faced with a home that is no longer an investment but a threat to the “financial security” of one’s family. To seal this argument in the public’s mind, he noted that corporations had no scruples about defaulting themselves: Witness Morgan Stanley’s 2009 default, despite record profits, on a $1.5 billion mortgage in San Francisco.

White’s message no longer seems so incendiary. He’s been quoted approvingly in such publications as The New Yorker and The New York Times. And White notes that Suze Orman, the queen of financial responsibility, has taken to advising homeowners to default if they’re underwater by 20 percent or more and the bank refuses to negotiate a short sale. Again and again, you can hear his thinking show up in the rhetoric of what The New Yorker‘s James Surowiecki sees as the beginnings of a “De-Occupy Your House Movement.”

In 2010, a Vancouver, Wash., man—who asks to be identified by his online name, “Izzle”—started to think about walking away from a house on which he owed $300,000, but which was then worth only about $225,000. Researching the matter online, he stumbled across a website called LoanSafe.org, which offers a forum for underwater homeowners to discuss their plight.

Strategic default was a popular discussion thread for posters from California, Nevada, Arizona, and Florida. But Izzle says he was one of the first from Washington to post on the subject. The housing crisis’ delayed local timetable, he figures, made strategic default a rare phenomenon in Washington. “A year later there are a lot of people from Washington [posting on the site],” Izzle says.

One LoanSafe member, “KentWalk”—she’s from Kent and walked away from her home—decided to invite local posters to get together in person to share their stories. In January, about 20 met for lunch at Bellevue’s Rock Bottom Brewery, according to Izzle, who attended. In late March, Izzle arranged another such lunch in Vancouver, and there is talk of yet another in Olympia.

Izzle declined Seattle Weekly‘s request to attend the Vancouver lunch because, he says, his cohorts wanted to talk freely. Judging by LoanSafe’s webpage, the conversation could have turned to some tactics that might raise eyebrows among the general public.

Consider, for instance, the “HAMPSTER wheel game” described on the site—so named after the federal Home Affordable Modification Program, which facilitates loan modifications for people within certain income ranges. “Here’s how a homeowner plays,” the website declares. “The homeowner has already decided to walk, but wants to stay rent/mortgage free for as long as possible. So the homeowner, even knowingly not qualified, submits the . . . [HAMP application process] to the loan servicer.” When the homeowner is inevitably denied, the homeowner can simply reapply or perhaps try for a short sale, thereby dragging out the process even longer—perhaps “for a couple years. This would indeed be a game well played!”

“And for bonus points,” the website continues, “here’s an added strategy. When the foreclosure sale appears imminent, the homeowner moves into new living accommodations, rents their home, and collects rent.”

This strategy isn’t entirely acceptable to lawyers in the field. Blackmon, for instance, says he thinks “acting in bad faith” through bogus applications to HAMP “is a bad idea.” Seattle real-estate attorney Lynn Arends says she warns homeowners against offering long-term leases for properties they’re about to default on. “That could be fraud,” she says.

But if defaulting homeowners rent out their places month-to-month, that’s a different story, Arends and others suggest. After all, somebody should live in the home to make sure it’s kept up. Defaulting or not, homeowners are responsible for their properties until the titles are transferred.For that reason, lawyers have no problem with homeowners staying put. “I tell clients to live there until the bitter end,” says Arends.

And bankers apparently prefer it that way. “It’s better to have people in the home,” says Jim Pishue, president and CEO of the Washington Bankers Association. “Vacant homes lose value.” Transients move in or homes fall into disrepair, dragging property values down throughout the neighborhood. In fact, he says that’s partly why banks are so slow to foreclose: They don’t want a whole lot of homes that are just going to sit vacant.

The banks’ unhurried pace furthers the opportunities to game the system, which is exactly what some of Jane’s Facebook friends thought she was doing. They called her a “freeloader” and a “squatter.” Jane’s mom, too, questioned her and Cory about the ethics of their decision.

Over coffee, the couple says they aren’t trying to pull one over on anyone. “My feeling is we’re on a sinking ship and we have to jump off,” Jane says.

She and her husband are quick to resort to numbers and technical specifications. “We’re engineers,” Cory says repeatedly. They hand over a chart they created which shows, assuming modest market growth, that they wouldn’t break even on their condo until 2029.

Cory, initially unsure about defaulting, says he became convinced after scrutinizing the mortgage contract itself, which he stresses has written into it the possibility and the consequences of defaulting. “We’re putting up collateral—our house—and if we don’t pay you back, you have the right to take the collateral,” he says.

He felt himself on even firmer ground when he looked up the state’s foreclosure laws. He found out that in Washington, unlike in some states, most foreclosures occur outside of court. These “non-judicial” foreclosures generally leave homeowners owing nothing, even if a property sells for far less than what is owed. That’s why some homeowners, in contrast to Heberling’s approach, favor foreclosures over short sales, which offer no such protection unless you’re crafty enough to negotiate it.

There are a few exceptions to these rules. If you have a second mortgage, that debt lingers after a foreclosure. More pertinent for Jane and Cory, a bank can decide to sue you for your full debt through a judicial foreclosure. The couple’s lawyer, however, thinks this is unlikely to happen.

The more likely legal pitfall is that they could be sued by their homeowners’ association should they default on their $300-a-month dues in addition to their mortgage. Attorney Dean Pody, who specializes in representing condo associations, says he’s frequently tasked with going after deadbeat residents. Associations have little choice but to sue, he says, because they’re struggling to raise money for necessary repairs at a time when significant portions of their complexes are in default.

Pody recalls one suit against a “professional athlete”—he won’t say who—who stopped paying dues after he left town for another team and walked away from his condo. The athlete, Pody says, was making more than $4 million a year, yet refused to pay $20,000 in back dues.

The problem, Pody says, is compounded by the recent trend of banks to be even slower to foreclose on condos; he says it can take up to three years. Many speculate that this is because banks are on the hook for association dues once they assume ownership.

Jane and Cory say they understand this issue, and have therefore decided to continue to pay their dues. “We didn’t feel like stiffing our neighbors,” she says. They have no such concern, however, about their bank—an institution Jane associates with public bailouts, excessive bonuses, and “heartless” behavior.

Day 1 of their adventures in defaulting began on March 1. The calls from the bank started coming immediately, and daily.

“You have no obligation to even be polite,” their lawyer advised. “Just hang up.” The attorney was concerned that the bank might find out the couple has money, and decide to exercise the rare option of a judicial foreclosure. Jane and Cory do one better and don’t answer their home line at all. “That’s what cell phones are for,” Jane says.

Jane also plans to close her current bank account and move her money to a credit union. That way, she figures, the bank that holds her mortgage (which at one time got automatic payments from her account at another bank) won’t be able to track her money. It’s a move that corresponds nicely to her new anti- banking credo. “Part of this economic adventure has been realizing that I don’t want to be with a bank anymore,” Jane writes on her blog.

She also outlines her “next plan of action”: improving her credit score as much as possible before the looming tumble. She went to a website called Credit Karma and found that her score would improve if she had more credit cards. So she applied for a new one, also from a credit union.

“My credit score went up one point!” she says laughingly. It’s not much compared to the hundreds of points it will soon fall. But then again, she figures, so many people have foreclosures on their records that standards are a lot lower than they used to be.

At least for landlords, that definitely seems to be the case. “It’s not a big problem getting a rental if you’ve gone through a foreclosure,” says Tim Seth, president of the Washington Landlord Association. In fact, he says that some landlords see a past foreclosure in favorable terms, reasoning that the prospective tenant “had the get-up-and-go to buy the house in the first place.”

The decreasing stigma attached to foreclosures would seem to foretell even more strategic defaults down the road. But Glenn Crellin, associate research director for the University of Washington’s Runstad Center for Real Estate Studies, doesn’t think so. He ventures that more homeowners may instead choose to refinance, because, for the first time, the feds are rolling out a program that may actually work.

Known as HARP 2.0 (the Home Affordable Refinance Program, a revamped version of the original), this program is designed specifically for underwater homeowners. And it doesn’t matter whether you’re financially strapped or not, making it a good fit for potential strategic defaulters. In fact, HARP 2.0 requires participants to be current on their mortgages, which Crellin says may give people incentive not to default.

Matthew Gardner, a Seattle real-estate consultant catering to corporations and public entities, also hazards that the exodus of people from their homes may be slowing. Exhibit A: King County currently has the lowest inventory of houses for sale it’s had in years. In March, just over 5,000 single-family homes were on offer—less than half the number on the market in 2008.

“A lot of people are waiting,” Gardner speculates. “They’re seeing signs of stability and hoping for modest price increases.”

But there’s another possibility, Gardner acknowledges: The sparse inventory might reflect, at least to some extent, the number of houses that are in a kind of netherworld, their owners defaulting and waiting for the banks to foreclose—a theory bolstered by the recent high default figures. There’s even a name for this reservoir of forfeited homes: “the shadow inventory.”

Just how many Tamis, Rons, Janes, and Corys are out there, though, is a question that escapes even the best real-estate economists. Says Gardner, “That’s the great unknown.”