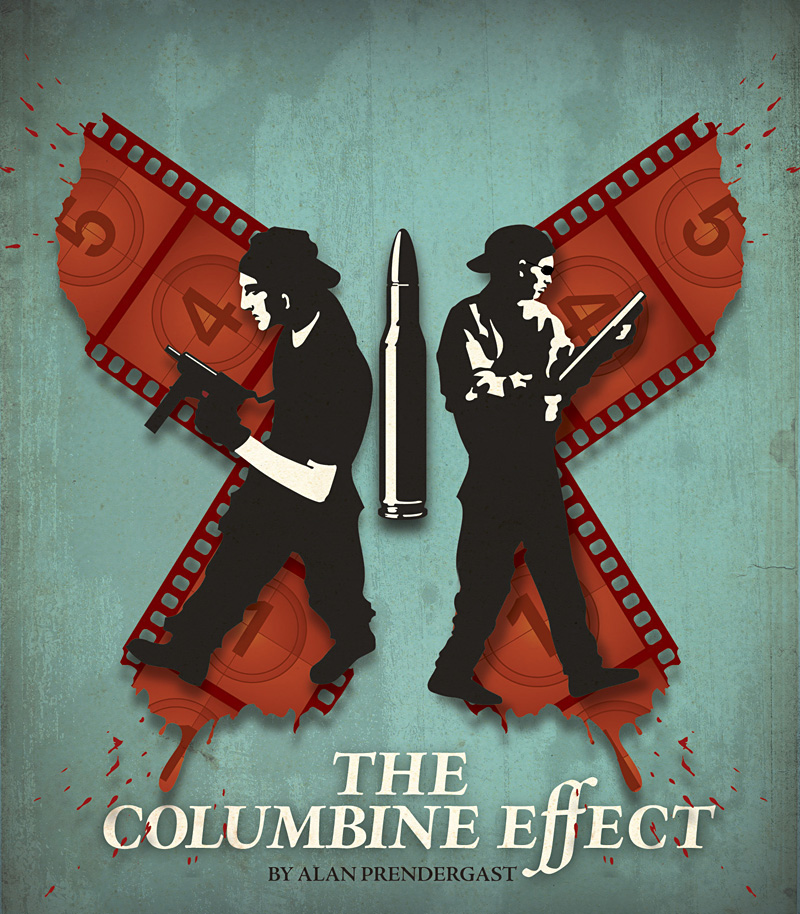

The news first surfaced in the Hollywood trade press last month: The Lifetime cable network is developing a miniseries about the 1999 school shootings at Columbine High School in Littleton, Colorado. Based on a best-selling book about the tragedy, the project involves a team of heavyweight producers whose collective film credits include the fact-based dramas Moneyball, The Social Network, and Boys Don’t Cry.

Sam Granillo heard about the miniseries on Facebook a few days later. “When I read about it—I don’t know if furious is the right word, but I was intensely emotional,” says Granillo. “I was beyond irritated.”

Granillo, 30, is a cameraman and production assistant who’s worked on a slew of commercials and television programs, from MTV’s Extreme Cribs to American Idol. But his interest in the proposed miniseries goes deeper than professional curiosity. A couple of lifetimes ago, he was a 17-year-old junior at Columbine.

On April 20, 1999, Granillo was eating lunch in the school cafeteria, known as the Commons, when seniors Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold began shooting students outside. The pair soon entered the school, firing randomly at cornered teens and tossing pipe bombs. Hundreds of people fled. Granillo and 17 others ended up trapped in a small room in the kitchen area, listening to shots, screams, and explosions. The door had no lock, so Granillo planted his feet against it.

In about 50 minutes, Harris and Klebold killed 12 students and one teacher, injured 21 others, then committed suicide. The ploddingly methodical SWAT rescue teams didn’t reach the kitchen for almost three hours. The police led Granillo and the others through a broken window, past pools of blood and lifeless bodies on the ground outside. Some of those bodies had been friends Granillo knew well. He’d also known Klebold since he was 10 years old—or thought he’d known him.

Past the scenes of carnage was a battery of police investigators demanding written statements, reporters trolling for eyewitness accounts, and television cameras poised to soak up the shock and grief. For weeks, survivors of the attack were stalked. Tabloid journalists offered hard cash for a hot-off-the-presses copy of the school yearbook, racing to be first to publish the killers’ senior photos. The headlines went on for months, followed by “anniversary stories,” documentaries, books, and even feature films loosely based on the shootings.

Even when he thought he was through the mourning process, Granillo found that Columbine wasn’t through with him. He had bouts of anxiety, recurrent nightmares about being chased and trapped. “At first the coping mechanism in my brain downplayed a lot of what happened to me, but it stuck with me,” he says. “Then I wanted to get counseling, and I kept running into dead ends . . . I’ve had people come up to me and say, ‘Sam, it’s been 10 years. Aren’t you over it yet?’ But it’s never going away for us, ever.”

A few months ago, Granillo began to raise funds and conduct preliminary interviews for a documentary about the long-term trauma left by the shootings. He figured this might be a way for him and others to put the tragedy to rest, to take the discussion in a new direction.

Then he heard about the miniseries. A true story about the worst day of his life, of his friends’ lives. A true story. Based on actual events. Told by people he’s never met.

“Anyone who wasn’t there doesn’t understand how we feel about having our lives put on display for everyone to see,” he says. “Who would want that? I’m worried for my friends who are going to turn on the television and see themselves portrayed as who knows what. A miniseries? That’s like the fucking straw that broke the camel’s back.”

Another Columbine graduate soon launched an online petition, “Say ‘No’ to Columbine Movie.” Within a week, thanks largely to social-media activism among alums and their families, the petition had collected more than 5,000 signatures. Some of the protesters posted comments expressing their displeasure with the project’s source material: Columbine, a book by journalist Dave Cullen, who bills himself as “the nation’s foremost authority on the Columbine killers.” Cullen’s book won awards and made several critics’ best-reading lists for 2009, but it’s had a rougher reception in Littleton, where some prominent members of the Columbine community have taken issue with its accuracy.

Other signers were troubled that the network backing the miniseries is Lifetime, purveyor of turgid melodramas involving cheating spouses, suave serial killers, and Tori Spelling. (“Lifetime should stick to cheesy movies about pregnancy pacts and Dance Moms,” one wrote.) But the prevailing sentiment seemed to be that any film project purporting to be the “real story” of Columbine, yet put together by outsiders, would reopen wounds not yet healed and possibly inspire more copycat shootings.

“This is a terrible idea for a movie,” wrote Columbine grad Anne Marie Hochhalter. She figures in several passages in Cullen’s book; she was one of the first students shot outside the school and was left paralyzed by her injuries. Her mother’s suicide a few months later provides another graphic scene. But Cullen never interviewed Hochhalter; his accounts of her family’s ordeal, complete with quotes, come from various news articles.

“It felt kind of violating, to be honest,” Hochhalter says of the experience of reading Cullen’s book. “He got the part about how I was injured completely wrong. I couldn’t bear to read the whole thing. The fact that this movie is in the works, based on what he wrote—I just feel sick over it. I don’t want young, impressionable, angry people out there, who idolize Harris and Klebold anyway, to see this on film.”

Cullen, who now lives in New York City, says he’s surprised by the virulent opposition to the miniseries. The project has been “in development” for years now, but he cautions that it hasn’t been “greenlit.” There isn’t even a finished script yet.

“When the book came out, I braced for possible controversy, and there wasn’t much,” he says. “People who don’t like the book probably aren’t going to like the film. But with the film, we don’t have anything for them to judge yet. It’s frustrating.”

Although it’s drawn the most ire, the miniseries isn’t the only Columbine-themed project in the works. A stage play based on Cullen’s book is also planned, and the film We Need to Talk About Kevin, starring Tilda Swinton as the mother of a Harris-like teen killer, has been making the festival rounds and is currently playing in Seattle.

Most of the students who attend Columbine today aren’t old enough to have any direct memories of the attack. But events keep the school’s dark legacy alive—for instance, the chilling fact that there have been more than a hundred school shootings since Columbine, including the shot that seriously wounded a Bremerton eighth-grader a month ago when a gun in a classmate’s backpack accidentally went off.

If you include college-campus violence, there were deadlier school shootings before Columbine (University of Texas, 1966) and afterward (Virginia Tech, 2007). Harris and Klebold had hoped to kill hundreds more, with bombs planted in the Commons and the parking lot, but their plan failed miserably. Yet Columbine remains the touchstone—the standard by which other horrors are measured and the archetype for Harris-and-Klebold wannabes. That our culture is still so fascinated by the shootings 13 years later may have more to do with the powerful myths woven around the tragedy—by the media, the killers, law enforcement, and others—than the “actual events” of what happened that day.

“Directors will be fighting over this story,” Klebold bragged in one of the so-called basement tapes, the videos the pair made in the weeks before the attack. It was just about the only prediction the killers got right.

But whose story is it?

“We all have hundreds of stories about what happened that day and since,” says Granillo. “But that’s not the story they keep telling.”

Klebold and Harris began planning their grandiose suicide mission more than a year before the attack. Amid all the fantasizing and strategizing, it’s clear they were aiming for something quite different from the rash of late-’90s school shootings in places like West Paducah, Kentucky, and Jonesboro, Arkansas.

“Do not think we’re trying to copy anyone,” Harris announced on one of the basement tapes. “We had the idea before the first one ever happened. Our plan is better, not like those fucks in Kentucky with camouflage and .22s. Those kids were only trying to be accepted by others.”

The Columbine killers weren’t interested in being accepted. In addition to a high body count, they wanted posthumous fame. And followers. They wanted to “kick-start a revolution,” as Harris put it.

Yet their bombs failed to detonate. The revolution never arrived. And their few imitators tended to be mental cases like Virginia Tech’s Seung-Hui Cho. The pair did, however, manage to achieve a degree of infamy that’s eluded other school shooters.

One reason for the persistent fascination with Columbine has to do with local law enforcement’s inept response to the attack. While the first Jefferson County Sheriff’s Office deputies on the scene exchanged shots with Harris, they didn’t follow the killers inside the school; instead, they waited for SWAT to arrive and conduct a time-consuming, room-by-room sweep. Meanwhile, the killers were free to fire at will at unarmed targets. (They killed themselves around the time the first SWAT team entered at the opposite side of the building, but police didn’t discover their bodies for three hours.)

The entire sorry spectacle unfolded on national television that afternoon. News copters caught images of hundreds of cops standing around outside, seemingly helpless; throngs of terrified students fleeing with their hands in the air; a sign in a window announcing that teacher Dave Sanders, shot while trying to shepherd students to safety, was bleeding to death in a science classroom. (He died before medical aid could be safely escorted to him.) No other school shooting had ever attracted such a massive live audience before—and new procedures, adopted in Columbine’s wake by police across the country, designed to deal swiftly with an active shooter situation make a repeat of such a prolonged siege unlikely.

The blundering continued long after the siege ended. Fearing civil suits, school and law enforcement officials lawyered up, releasing little information about the killers and even lying about a prior police investigation of Harris for making threats and detonating pipe bombs. Determined to explain the “why” of the shootings, journalists fashioned motives out of rumors, cranking out stories about Harris and Klebold as persecuted goths, members of the Trench Coat Mafia, or put-upon nerds looking for payback against bullying jocks.

The truth trickled out gradually. Under pressure from the victims’ families, the Jefferson County Sheriff’s Office grudgingly released some of its investigative files, while fighting for years to suppress some of the most embarrassing documents—as well as the killers’ writings and videos, claiming they would provoke copycat shootings. (The basement tapes, though viewed by some reporters and Columbine families, are still officially under wraps.) The stonewalling made these materials seem far more interesting than they actually were, helping to perpetuate a mystique about Columbine that endures to this day.

The media mythology quickly became fodder for film and television dramas—everything from high-minded indie features to episodes of Law & Order, Cold Case, One Tree Hill, and even American Horror Story. The feature films tend to fall into two camps, focusing either on the killers as some inexplicable evil force, or on the aftermath of a school shooting, in which survivors search for solace and explanations. The latest entry is Lynne Ramsay’s We Need to Talk About Kevin, the artiest, darkest shooter film since Gus Van Sant’s Elephant (2003). Like Van Sant, Ramsay doesn’t offer much accounting for the bad seed who decides to practice his archery on his classmates. (Even Kevin, who survives the attack, doesn’t have much in the way of motive to offer: “I thought I knew,” he says.)

So far, Kevin hasn’t stirred any noticeable outrage among Columbine alums. None of the other filmmakers’ interpretations generated much controversy, either. But then, none of them claimed to be the “real story” of Columbine.

The petition opposing Lifetime’s miniseries was started by a Las Vegas stagehand named Michael Berry. A 2001 graduate of Columbine, Berry was sitting in his guitar class in the school auditorium when two students came in and said guys with guns were running around. As the shots and explosions drew nearer, Berry’s teachers locked the doors. Later, a janitor showed the class a safe way out of the school. They ran to a nearby park, where other students milled about in a general panic.

After the initial shock, some students and parents pressed for things to “return to normal” as soon as possible. Berry found that difficult. In his senior year, his English class went to see a production of Hamlet set in the 1920s. “The director didn’t tell my teacher that at the end of it, the lights go out and guns start firing,” he recalls. “A lot of my class had a real hard time with that.”

Berry says he doesn’t have a problem with Cullen’s book, which he hasn’t read. But he believes an effort to dramatize the “actual events” of Columbine will do more harm than good. “I still have a few tics and triggers,” he says. “I just don’t understand what is going to be added to the conversation.”

Cullen is well aware of the range of objections to the miniseries. He read through comment after comment in the online petition, trying to understand his critics’ perspective, but finally gave up. “It was demoralizing,” he says. “A lot of them were calling me a horrible person.”

It stung, he says, that people think the project is just about money, as if anything dealing with Columbine is a guaranteed blockbuster. He spent the better part of 10 years researching his book and challenging the core myths about the attack—for example, that Harris and Klebold were out to kill jocks—but most major publishers weren’t interested. Even after the book won rave reviews, major studios passed on the idea of an adaptation. “It was this project nobody wanted to do, based on this very dark material,” he says.

After some high-profile industry names became attached to the proposal—writer/director Tommy O’Haver (An American Crime) and producers Michael De Luca (Moneyball, The Social Network) and Christine Vachon and Pam Koffler (Boys Don’t Cry)—Lifetime became interested in it as a “prestige project,” something to help change the network’s image.

Cullen expects to have considerable input into the adaptation. He doesn’t anticipate that the miniseries will inspire copycats, because the “actual” Harris and Klebold, stripped of their mythologies, “are pretty unappealing.” For economy’s sake, the script may contain composite characters on the periphery of the story, but the intent is to tell a true story: “It’s definitely all real names, real people, keeping it as real as possible.”

Yet it’s precisely this assertion of the project’s authenticity that most troubles its opponents. In the Columbine community, Cullen’s book is widely regarded not as the definitive account of the massacre and its aftermath, but as one version of it, with its own biases and questionable interpretations. The second chapter portrays Harris as a chick magnet, an assertion based largely on the account of one reputed girlfriend whom police investigators concluded wasn’t credible; several people who knew the killers well believe both Harris and Klebold died virgins. (“Right now I’m trying to get fucked and trying to finish off these time bombs,” Harris wrote two weeks before the attack.) It’s one thread in a larger dispute some readers have with Cullen’s work—which in their view downplays the role of bullying and other factors in its efforts to portray Harris as a well-integrated psychopath and Klebold as his depressed, rejected follower.

It’s doubtful that even the most nuanced interpretation of the killers’ motives would satisfy all camps. Harris and Klebold offered contradictory explanations for their hatred and despair. They were filled with rage over perceived slights from family members and the “bitches” who rejected them, but also believed they had “evolved one step above you fucking human shit.” They offered ample warning signs of their intentions because they suspected, correctly, that almost no one was paying attention. They pursued their apocalyptic plot for months, with the monomania of terrorists, even as their lives seemingly improved, yet they were adept at blaming others for their isolation and contempt for the whole world. “I hate you people for leaving me out of so many fun things,” Harris wrote in the final, self-pitying entry in his journal. That’s not an explanation—just another expression of long-nurtured grievances by an angry, deeply delusional teenager.

A few of Cullen’s most vocal critics say they don’t trust his book because he relies so heavily on sources among law enforcement and school officials, including Jefferson County lead investigator Kate Battan, FBI agent Dwayne Fuselier (whose psychological analysis of the killers Cullen presents as if handed down from Mount Sinai), and principal Frank DeAngelis—people whom Columbine families accused of misleading them or providing self-serving accounts. Although Cullen deals in a roundabout way with the police cover-up of prior investigations of the killers and their blunders on the day of the attack, he also describes the Jefferson County commanders—several of whom lied outright to the media and the victims’ families—as “essentially honest men,” and makes a point of proclaiming that Battan “was clean.”

“He was working with Battan and Fuselier to make the police look good,” says Brian Rohrbough, who fought in court for years to establish that the official account of how his son Danny died outside the school was wrong. “He glosses over the cover-up as if it’s an incidental thing.”

When Columbine was published three years ago, Rohrbough and other parents were incensed to learn that Oprah Winfrey was going to feature the author, Battan, and Fuselier on a show marking the shootings’ 10th anniversary. Contacted by a producer for photos of his son, Rohrbough suggested that Winfrey was making a terrible mistake. “I said, ‘I’d be happy to pay for my own plane ticket and be part of this,’ ” he recalls. ” ‘If you’re going to put these liars on, someone needs to be there to refute them.’ She was horrified.”

An appearance on Oprah virtually guarantees a dramatic rise in sales for any author. Winfrey decided to shelve the episode on Cullen’s book, issuing a brief statement: “After reviewing it, I thought it focused too much on the killers. Today, hold a thought for the Columbine community. This is a hard day for them.”

Cullen points out that Columbine also deals with the recovery process of survivors and victims’ families—especially Patrick Ireland, the badly wounded youth who crawled out of the library window into the arms of rescuers, and the wife of Dave Sanders. His book was positively received by some of the Columbine families, as well as by thousands of people affected by other shootings and forms of trauma. He insists that the producers he’s working with are as committed as he is to honor the victims and not glorify the killers.

At the same time, he concedes that he doesn’t have an easy response for people concerned about the traumas the miniseries might trigger. “Of all the anger and reasons for protest, that’s the one that gnaws at me the most,” he says. “That’s the one I’m really worried about. You’d think I had a better answer for that by now.”

Cullen says he recognizes that the post-traumatic stress experienced by many of the survivors is genuine and ongoing. He had two diagnosed bouts of “secondary PTSD” himself while researching his book, one of which was triggered by a series of school shootings in the news in a matter of days. The two most emotionally trying chapters to write, he says, involved Sanders’ death and, oddly, Klebold’s funeral. “I couldn’t get any work done,” he recalls. “I was pretty much crying every day. I thought I would get over it. I was about three weeks into it when I realized I was in trouble. I was kind of a mess.”

But he believes the downside of revisiting the shootings is outweighed by the good that a thorough, honest treatment of the event could do. He likens the project to Vietnam movies of the late 1970s, which distressed some vets but helped the nation come to terms with the war’s legacy. “The whole country did go through Columbine, and really needs something that will help them,” he says. “So I think we need to do it.”

Sam Granillo and other petition- signers don’t agree. The miniseries controversy has only strengthened Granillo’s resolve to pursue his own documentary about how his classmates have dealt with the long-term legacy of the shootings. He recently launched a website to promote the project, now called Columbine: Wounded Minds, and has a fundraiser planned for next month. “There’s no reason to relive the tragedy endlessly,” he says. “There needs to be a new perspective of the situation, from us—and that has not been done yet.”

Many of the people Granillo is interviewing for his documentary had never before talked publicly about the attack. It’s difficult work, he says, and it’s easy to get off-track, as subject and interviewer start to reminisce about various friends they lost or share little stories about life at Columbine before everything was utterly transformed.

Recently Granillo sat down with DeAngelis, still at the helm of Columbine High after all these years, the person reporters seek for every anniversary story. For the first 45 minutes, the interview trudged forward as just another retrospective—the same canned questions and answers. Then Granillo asked his old principal what was really going on in his head, having to be the spokesman and public face of Columbine.

DeAngelis thought about it. He began to talk more candidly than Granillo had ever heard him talk before. The two spent the next four hours in conversation about the school they loved and mourned.

“It was both of us,” Granillo says, “sharing things we could relate to. Things we knew, that you had to be there to know.”

Alan Prendergast is a staff writer at Seattle Weekly‘s sister paper, Westword, in Denver.