In 1958, the moody, already-huge abstract painter Mark Rothko was commissioned to paint four large canvases for NYC’s new fat-cat culinary mecca The Four Seasons. John Logan’s award-scooping 2010 play (Tony, Drama Desk, you name it) imagines Rothko (Denis Arndt) hiring an ambitious young helper (Connor Toms as Ken, a composite of various Rothko assistants), whose attitude shifts from reverence to ridicule as Pop Art begins to supplant modernism. Though predictably Oedipal (the young man sharpens his own artistic vision on the grindstone of Rothko’s pompous hide), the arc is a satisfying one, especially as played out on Kent Dorsey’s studiously drab art studio set, where the breathtaking paintings are launched straight into your soul.

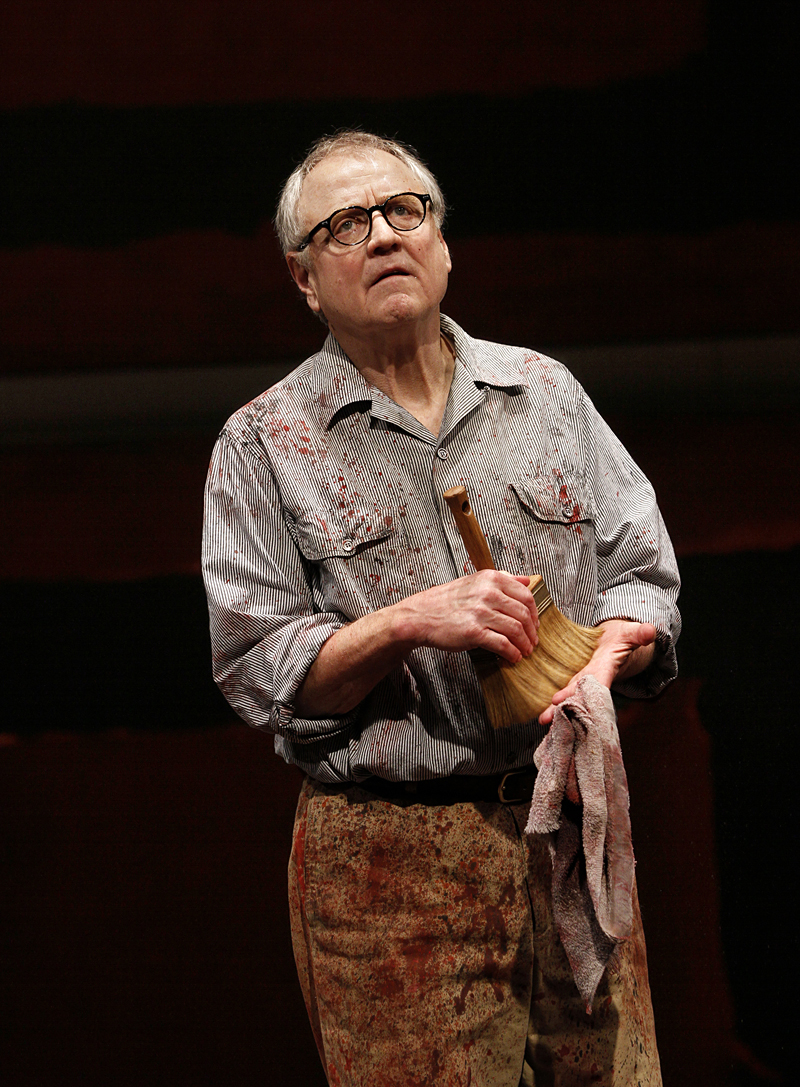

There’s something marvelously murderous about the image of Rothko working his reds like a blood-spattered butcher. (The artist would eventually butcher himself in 1970.) As directed by Richard E.T. White, the usually stentorian Arndt modulates Rothko into a waning lion, lending pathos to such sanctimonious utterings as “To surmount the past, you must know the past.” Toms, meanwhile, radiates increasingly confident physicality, as though he’s downed a power drink. Indeed, the pivotal scene of energy transfer involves the two of them racing to prime an oxblood-colored canvas, both putting their all into it, but Rothko winds up winded while Ken is kindled. Unfortunately, many scenes rely on verbal debate to convey this embattled torch-passing. But throughout their sparring, the actors convincingly perform inherently interesting tasks of their trade: frame-building, canvas-stretching, and priming. These absorbing details help the hackneyed arguments about the purpose of art go down more easily, as does the wry humor. While Rothko derides the “comic books and soup cans” of emergent Pop Art, Ken zings “So said the Cubist the second before you stomped him to death.”

Despite the many pleasurable aspects of this production, I remain skeptical that the enigmatic Rothko would have spent so much of his time pontificating to an employee. Logan, better known as a screenwriter (Gladiator, Hugo, Coriolanus), seems to be exploiting Rothko’s famous brand to attract an audience in precisely the way vacuous social climbers, whom the play’s Rothko criticizes, commodify his paintings. Whether that’s a clever irony or a blind stumble is, like the interpretation of art, up to you.