Six hundred miles southeast of Seattle, where they’d previously lived in the same small enclave, a photographer and two painters met again. There also in the Minidoka Relocation Center, in the Idaho desert where no white farmer would willingly settle, were their wives and small children. Most of their possessions were left behind—or sold under duress—back home. And when World War II ended, along with their illegal internment, they returned home to ruined lives, their art mostly forgotten.

Two ongoing shows are rooted in the neighborhood called Japantown that existed before World War II, before its population was incarcerated and dispersed, before it was split by I-5 and rebranded the ID. Photographer Henry Miyake is represented at the Wing with Vintage Japantown Through the Lens of the Takano Studio (through Feb. 12), which bore the name of the prior owner from whom he bought the place. Up at SAAM is Painting Seattle: Kamekichi Tokita & Kenjiro Nomura (through Feb. 19), with Tokita also the subject of a new biography.

Close by the Wing, the building that housed the Takano Studio is still standing, just around the corner from the former Noto Sign Co. (slogan: “Tell the world with signs”) that Tokita and Nomura ran as business partners. They were both hard-working Issei, first-generation immigrants legally excluded from gaining citizenship, with little free time to lug their easels around Seattle to paint street scenes. And many of those scenes on view at SAAM are immediately recognizable to anyone who walks the city today. Both depicted the intersection of Yesler and Fourth, for instance, from a grassy perch looking down at the overpass; and the museum presents the two views side by side—as, indeed, the two men often worked together in the open air. Their style was once called “American Scene,” a kind of Hopper-esque realism we today associate with WPA artists. (Both contributed to the Public Works of Art Project, a precursor to the WPA, and both were exhibited at the new Seattle Art Museum whose founder, Richard Fuller, was keenly devoted to Asian art.)

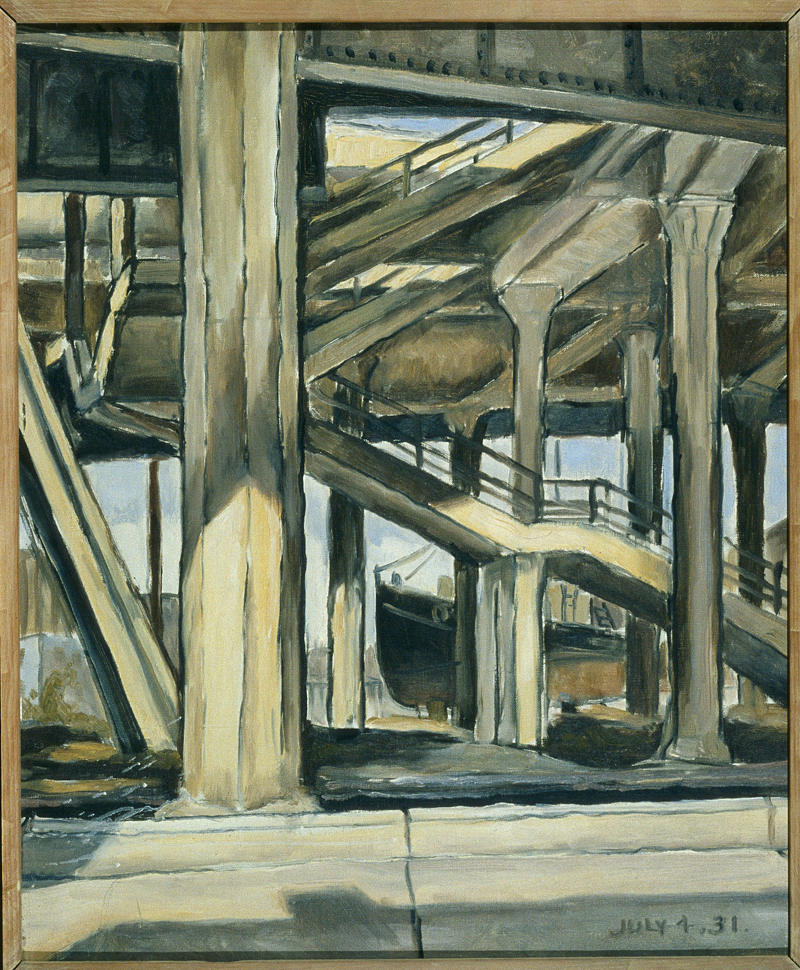

With just a handful of postwar abstract works by Nomura (1896–1956), these oil paintings are mostly empty of people, though there are traces of the bustle and commercial activity of Japantown. The street grid is often canted, the sky sliced by telephone wires. Rooflines, fishing boats, staircases, and bridge support beams are massed into diagonals; there’s a calm yet slightly off-balance aspect here, the opposite of serene, horizontal nature scenes. It’s the everyday world Tokita and Nomura lived in, not the world as they might’ve wanted it to be. Sign-age, appropriately, is often included in their frames—though not with the fine-brush precision used in their day job. On which subject, Tokita (1897–1948) notes in his diary: When the war begins, a dentist hires him to paint over the Japanese lettering on his storefront.

That and other personal details emerge in Signs of Home: The Paintings and Wartime Diary of Kamekichi Tokita (UW Press, $50) by curator Barbara Johns. Tokita began his diary on the night of December 7, 1941, as news of the Pearl Harbor attack was uneasily absorbed in Japantown. Before the war, the community had five newspapers; seven days after Pearl Harbor, the Japanese-American Courier asked Tokita to remove the two nations’ flags from its logo, “So I drew an illustration with a bald eagle.” Soon Japantown residents were required to surrender their radios and cameras, which effectively closed Miyake’s photo studio.

In a small, hard-to-find cubicle at the Wing (accessed through the large central “Honoring Our Journey” gallery, left at the top of the stairs), Miyake’s portraits are of families, weddings, seasonal celebrations, even baseball teams. (Go, Lotus Trojans!) Here are all the faces missing at SAAM, the documentary evidence of those who walked Tokita and Nomura’s streets. Japantown once extended from Pioneer Square to what was then called Yesler Hill. With the street grid intact (before the freeway, before the 1940 Yesler Terrace housing project), the slope was covered with small, modest wooden houses that Tokita and Nomura depicted. Miyake essentially shows us what was going on inside those homes on special occasions; his frames aren’t so much documentary as aspirational and commemorative. They say in part, “Look how assimilated we are. Look how American we’ve become.” (You can browse through 400 images from the studio archive at http://db.wingluke.org/takano.) Miyake was also an Issei, though his wife was American-born. Still, they and their child were shipped off to Minidoka. Included in the exhibit is one small souvenir Miyake brought back from Idaho, a small hand-painted stone, but no photos from his incarceration. (After the war, he revived and ran the studio into the ’70s.)

Conversely, Tokita did sketch and paint a little in Minidoka, though he wrote, “I’ve had a hard time finding scenery in our camp that inspires me.” Much of his time was spent doing carpentry, seeking to improve the barracks—one of which he depicts in drab, sandy yellows, a small planter box and garden the evidence of domesticity in exile. He and Nomura had parted ways before the war (the latter to run a laundry in the U District). Curiously, his diary hardly mentions his old friend, with whom he lived in the sign shop before both men married. Back in Seattle after internment, succumbing to diabetes, he seemed drawn to greener nature scenes denied him in Idaho.

If Nomura was then cautiously embracing abstraction (somewhat in the style of Mark Tobey), Tokita was instead looking back to simpler times. But it was Nomura whose reputation extended past the war, aided in part by the acclaim given George Tsutakawa and Paul Horiuchi. Asian art now mingled with modernism, and nobody was painting mundane street scenes anymore. Nomura was granted a posthumous solo exhibition at SAM in 1960. I-5 was completed a few years later, by which time Japantown was no longer a neighborhood, but a subject for museum shows.